A child in class at the Bridge International Academy in Embu, Kenya

After one year living in Kenya, my time here is fast approaching its end. In a few weeks, I finish work with Bridge International Academies. I am heading to Southeast Asia for a few weeks of rest and relaxation before moving to San Francisco to help my brother launch a start-up for the summer. After that, I am returning to school to pursue an MBA. And so ends my two and a half years on the road. This weekend, as I visited one of our schools, I was reminded about what a rewarding experience this has been.

I have lived in three countries – the Philippines, Ghana, and Kenya – and traveled to many, many more. I have learned an incredible amount and experienced things I never imagined I would experience. Much of it is documented on this blog. But the most rewarding parts have been the work and the people. Being a part of organizations whose missions have been to make things better for others less fortunate has been a privilege. Working with the folks who commit themselves and their time to realize the vision has been rich and rewarding.

This weekend, I had a chance to go see the grand opening of our 65th school in the town of Embu in the Central region of Kenya. I shared a taxi with a group of seven from the head office – members of the IT, research, government relations, training, and marketing departments were present. Embu is three hours from Nairobi and the scenery was pleasant. Once you leave Thika Road, the Chinese-built superhighway that is emblematic of the surge in investment in Africa from the East, and pass through Ruiru, the landscape becomes more rural and green. The rolling green hills felt more like Rwanda and Uganda, where flat ground is hard to find.

Rainfall – particularly during the rainy season in April – is high and the floodplains are ideal for growing rice. We passed the Del Monte pineapple farm, which made the farms I visited in Ghana look like the herb garden I had on my balcony in Boston. The lime-green rice paddies that followed reminded me of the rural areas on Negros Island in the Philippines, where I used to ride on the back of motorbikes and tricycles to visit borrowers. When we finally reached the school, everyone was excited to stretch their legs and get to work.

Construction on half the school continued as we helped with last minute preparations for the grand opening ceremony. Kids lined up to see the face painters, parents spoke to the teachers to learn more about the school, prospective children sat in class and went through lessons, and the community elders filed in to dedicate the school. It was great to be a part of such an important event.

Me with the newest teachers at Bridge International Academies

My days at work consist of sitting in an office, analyzing data, managing our longitudinal student testing, and generally sitting in front of my two computer screens, looking at Excel spreadsheets and word documents. When that is your job, it is easy to lose sight of what you are doing and why you are doing it. So visiting the school, watching the kids learning and seeing the excitement on the faces of the parents was important for me.

As I wind down my time here in Kenya, I am proud of the work Bridge International Academies is doing and the impact we are having on informal settlements and poor communities. Bridge has the potential to create a minimum standard of education for every child in the world that is much higher than it is today. Hands-down, it is the most innovative company in the education space at the base of the pyramid and has created a model that will be studied and replicated by organizations across the world. I will be sad to leave, but I am optimistic that the company will change the world. Loyal readers know that a cynic like me is hesitant to use that expression for anything. Mine has been an exciting and meaningful experience, and the trip yesterday really drove that point home.

Here are some of the photos of the trip:

Develop Economies Music Recommendation

I met Dickens, a research associate with the company, near the Hilton Hotel in downtown Nairobi. After a quick breakfast, we walked a half hour through markets, past the bus station where a group of al-Shabaab sympathizers recently threw four grenades into a crowd of people, killing four and wounding dozens more. We picked up a matatu heading to Lunga Lunga, the densely-populated slum in the industrial area near the airport, arriving at around 9 in the morning. This is the same slum where a

I met Dickens, a research associate with the company, near the Hilton Hotel in downtown Nairobi. After a quick breakfast, we walked a half hour through markets, past the bus station where a group of al-Shabaab sympathizers recently threw four grenades into a crowd of people, killing four and wounding dozens more. We picked up a matatu heading to Lunga Lunga, the densely-populated slum in the industrial area near the airport, arriving at around 9 in the morning. This is the same slum where a

The link between poverty and terrorism is well-known. In theory, one of the purposes of organizations like USAID is to complement the other “D’s” of the foreign policy apparatus – diplomacy and defense – to improve conditions for people most likely to be driven to desperation: the poor. It is not surprising that the hotbeds of terrorism today – Afghanistan, Yemen, Somalia, Pakistan, Indonesia – happen to be some of the poorest countries in the world. Nor is it surprising that many of these countries receive the lion’s share of foreign aid from the U.S. government, despite their apparent animosity toward the country. The Nesaji cotton-and-wool factory in Kandahar is a

The link between poverty and terrorism is well-known. In theory, one of the purposes of organizations like USAID is to complement the other “D’s” of the foreign policy apparatus – diplomacy and defense – to improve conditions for people most likely to be driven to desperation: the poor. It is not surprising that the hotbeds of terrorism today – Afghanistan, Yemen, Somalia, Pakistan, Indonesia – happen to be some of the poorest countries in the world. Nor is it surprising that many of these countries receive the lion’s share of foreign aid from the U.S. government, despite their apparent animosity toward the country. The Nesaji cotton-and-wool factory in Kandahar is a

The flagship of the Sachs camp is the Millenium Villages project, a $150 million, multi-country intervention that exemplifies the concept of “the big push.” The systems that underlie the poverty trap are extraordinarily complex, layered, and multi-faceted. According to the top-down school of thought, it is possible to change the entire system only by changing its key components. The Economist

The flagship of the Sachs camp is the Millenium Villages project, a $150 million, multi-country intervention that exemplifies the concept of “the big push.” The systems that underlie the poverty trap are extraordinarily complex, layered, and multi-faceted. According to the top-down school of thought, it is possible to change the entire system only by changing its key components. The Economist  In order to do anything, you have to do everything. Being on the ground, you see the complexities of the system at work. Everything is interrelated and connected in a complex web. Change an input here or there and you can transform the system. But, more often, well-reasoned tweaks to the system have unintended consequences. What is more, it is question whether even the smartest economists can truly comprehend that sheer magnitude of the forces at play. They are, after all, global by nature.

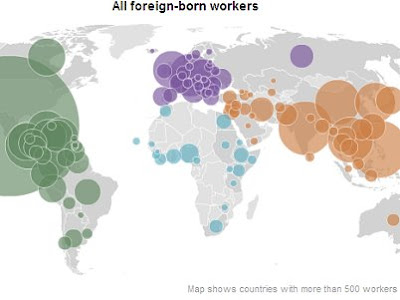

In order to do anything, you have to do everything. Being on the ground, you see the complexities of the system at work. Everything is interrelated and connected in a complex web. Change an input here or there and you can transform the system. But, more often, well-reasoned tweaks to the system have unintended consequences. What is more, it is question whether even the smartest economists can truly comprehend that sheer magnitude of the forces at play. They are, after all, global by nature. Human capital flight – otherwise known as “

Human capital flight – otherwise known as “ Microsoft is only one example. The company and industry are secondary to the work environment, which emphasizes the importance of intangibles, like time management, prioritization of tasks, and quality control. Working for an American company like General Electric, for example, might teach someone the importance of optimization in manufacturing, while working for Target shows them the importance of customer service in maintaining client relationships. Then, when they return to their home countries and start their own business, they bring with them those industry-specific best practices. As a result, they are more competitive in the domestic market, forcing competitors to either adapt or die. Ultimately the economy becomes stronger and more competitive.

Microsoft is only one example. The company and industry are secondary to the work environment, which emphasizes the importance of intangibles, like time management, prioritization of tasks, and quality control. Working for an American company like General Electric, for example, might teach someone the importance of optimization in manufacturing, while working for Target shows them the importance of customer service in maintaining client relationships. Then, when they return to their home countries and start their own business, they bring with them those industry-specific best practices. As a result, they are more competitive in the domestic market, forcing competitors to either adapt or die. Ultimately the economy becomes stronger and more competitive.

.jpg)

The

The

There is a fierce debate going on right now in India about a new piece of legislation that that will allow multi-national corporations to operate as joint ventures in the country, owning up to 51%. And a week ago, the Indian government backtracked and announced that it would not pass the legislation after all. It is worth examining the potential pros and cons.

There is a fierce debate going on right now in India about a new piece of legislation that that will allow multi-national corporations to operate as joint ventures in the country, owning up to 51%. And a week ago, the Indian government backtracked and announced that it would not pass the legislation after all. It is worth examining the potential pros and cons.