![]()

This is part two of a two-part post about amateurs vs. professional in aid and development.

In my experience, development professionals tend to be a jaded and cynical bunch, but also eternally optimistic, well-meaning, and principled. In one post, a blogger who writes “Good Intentions are Not Enough” (another blog I read and respect) explains what it means to be an “aid professional.” Here are a few:

- First and foremost – Do No Harm – whether what we do is right or wrong, we are doing it to the people that can least afford for us to fail.

- There is a need for fresh perspectives and a variety of ideas and approaches. However this must be tempered with knowledge of the factors that led to success and failures in the past so the same mistakes are not constantly repeated.

- Stick around long enough for projects to have a chance to fail. Then try to stop them from failing and learn from your mistakes.

While I agree with these principles, I don’t think the status quo promotes them. In Algoso’s article, he explains how failed projects sap money from potentially successful projects. Yet Good Intentions is right – we need to learn from mistakes. Some of my good friends in Ghana worked for Engineers Without Borders Canada. One was a mechatronics engineer, another a geoscientist (by training, not profession). The amateurs at EWB Canada even created a website called “Admitting Failure” and held a conference called FailFaire, which is cited by professional development workers as a step in the right direction. To fault “amateurs” for their mistakes, while saying experts should learn from theirs is a bit hypocritical in my opinion.

Regarding the second point – how can experts bring a fresh perspective if they all draw from the same pool of knowledge? Successful projects bring expertise and best practices from many different fields and apply them to development. This is how you bring fresh ideas.

And, most importantly, regarding “do no harm,” I have seen aid projects literally destroy the rural banking sector of a country. In this particular case, it was a multi-million dollar government aid project. Not to mention, the amount of collaboration between aid agencies from different countries is appalling. I once sat in a meeting between aid officials from two governments who found out that they had been training the same group of farmers on the same skills for the past six months and didn’t even know it. Of course, do no harm. But don’t assume that amateurs will do more harm than “professionals”.

In my personal experience, the organizations I have worked with run the gamut from large-scale bureaucratic government aid projects to the one of the most capitalist social enterprises around. And, frankly, the most innovative and effective are the ones founded by development amateurs with a professional background in other fields – the self-taught warriors who bring their insight and skills from other industries to bear on the social sector.

My intention isn’t to say that everyone with a masters degree in international development and a resume overflowing with public sector and development experience is wrong about everything. Clearly, that experience is valuable in understanding context and knowing what has worked and not worked in the past. It is particularly relevant in the policy sphere – designing programs like Bolsa Familia or advising governments on legislation and policy.

My intention isn’t to say that everyone with a masters degree in international development and a resume overflowing with public sector and development experience is wrong about everything. Clearly, that experience is valuable in understanding context and knowing what has worked and not worked in the past. It is particularly relevant in the policy sphere – designing programs like Bolsa Familia or advising governments on legislation and policy.

Rather, I want them to recognize the critical role amateurs play in this work. They bring new ideas, enthusiasm, optimism, and much-needed skills. They may not always succeed, but, if history is a guide, applications of traditional development theory haven’t produced overwhelming results either. If the CEO of a company had the same track record of results as the development experts during the past four decades, he would have been fired without a second thought.

The second and more important point is that this “leave it to the experts” mentality is far more destructive in the long-run than the trial-and-error nature of DIY foreign aid. Algoso explains that failed ventures take money away from other projects and ventures that might work. This, to me, is a recipe for the status quo – an approach to poverty alleviation and economic development marked by a lack of innovation, fresh ideas, and competition for funding dollars.

Take the Millenium Villages Project – a massive top-down development project thought up by a bunch of “experts” at the Earth Institute at Columbia University. The brainchild of Jeffrey Sachs – one the most influential economist in the world whose commitment to the cause no one can deny – the MVP has been criticized for its high costs and limited impacts. At a cost of $300,000 per village per year, the project achieves modest gains that, frankly, will do nothing to solve the much larger problem of food security in the regions it serves. This, to me, is a good example of an unsustainable project and a waste of money in development.

Among the amateurs, on the other hand, the failure rate may be high, but successes can be far greater. Play Pumps may have been a failure, but what about Kiva? Kiva – an online peer-to-peer lending organization that uses the Internet to connect lenders with borrowers around the world – might the most successful and effective non-profit in modern history. It has more than one million users and has distributed over $250 million in loans to borrowers in 216 countries. The video above, titled “Intercontinental Ballistic Microfinance,” shows a stunning visual displays the movement of Kiva loans around the world. More importantly, unlike Millenium Villages, it is fully financially sustainable – something that is paramount to the founders, who cut their teeth at PayPal. It is a good thing that Matt Flannery and Premal Shah didn’t decide to return to their day jobs and leave it to the experts.

World Vision

For a more tangible example, the first comment on the article is illuminating. It is from someone who works for WorldVision. For those who do not know, World Vision is the organization that distributes the Super Bowl t-shirts in Zambia, and is responsible for undermining the local cotton industry throughout sub-Saharan Africa. This practice is widely reviled by the “professionals,” and resulted in the online castigation of a poor sole from Florida named Jason Stadler who tried to get donations of one million shirts. Apparently, the irony is lost on experts. In any case, here is what the World Vision employee has to say:

This is not something amateurs should be meddling in but unfortunately starting your own non-profit is the new “starting your own business”.It is absolutely petrifying to me that independants are starting nonprofits, especially the often open access some are giving donors to vunerable children. They are also fostering a mentality of donor needs before community desires.

The next comment comes from someone who works in a rural village in Lesotho, who isn’t a fan of World Vision and raises very specific criticisms of the organization:

World Vision! This is one of the worst organizations with the least understanding of local conditions, cultures and solutions; they chase huge amounts of money in the name of religion.

The World Vision employee then gives a puzzling response:

I think you point out something really valid – INGOs make mistakes. We have made mistakes, which we are bound to do after 60 years of working in communities. We are after all a human organization and humans make mistakes and in some circumstances, get everything wrong.

We are encouraged not to hide those mistakes. To talk about them, learn from them and to try not to repeat them. I think that’s why I find it scary to think of a bunch of rouge nonprofits coming in without having lessons learned. Its more about the experience than it it is about credentials.

This, to me, is the essence of the professional aid workers mentality. They condone mistakes made by professionals and condemn them from amateurs. If the professional fails, it is a learning experience. If the amateur fails, it is destructive.

So here is my advice to anyone who is thinking about quitting their job and taking up the cause of making the world a better place: do it. Don’t hire a professional. Don’t even try to become a professional. Should you read a book or two about what works and think about how you can maximize your impact without being detrimental? Definitely. But be wary of what they tell you, because, for the last 40 years, they have largely gotten it wrong. You don’t need an MBA to start a business, and you don’t need a degree in international development or a job at an aid organization to make a difference.

Ignore the “professionals” telling you to leave this work to the experts. Try something. If you fail, learn from it. If you succeed, share it, and help others to scale. Don’t be deterred by people telling you that you don’t have the experience. Just go out and do it.

Over the past two years, I have seen innovative and creative minds building great things. When I do, I am reminded how refreshing it is to be one of the amateurs.

DEVELOP ECONOMIES MUSIC RECOMMENDATION

One sign that the U.S. political scene has reached rock bottom is David Brooks writing one of his weekly columns about development workers in Nairobi. In “

One sign that the U.S. political scene has reached rock bottom is David Brooks writing one of his weekly columns about development workers in Nairobi. In “ A friend posted an article on his Facebook wall titled “

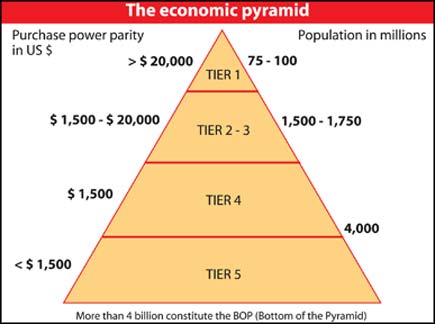

A friend posted an article on his Facebook wall titled “ There is a myth of a fortune at the bottom of the pyramid, according to Toyama. At least, that fortune is purely measured in market size and raw purchasing power. It should not be confused with an opportunity to offer products that alleviate poverty and make a bundle to boot. The rural and even urban poor are difficult markets to serve profitably. A disparate and sometimes non-existent supply chain makes getting products in the hands of consumers a challenge even for the biggest multinationals. Branding products for the poor, or subsidizing them, makes them less appealing to the middle class, who might pay more and create cross-subsidization opportunities (on this point, I think he is wrong, having seen the same solar lanterns we were selling to microfinance clients in the Philippines being sold in malls in Manila for twice the price). Not to mention, selling products to the poor is not going to help them out of poverty. Employment, in the form of manufacturing and labor-intensive work, is the key to growth. In short, it is possible to serve a social cause, and it is possible to make lots of money selling products to the poor. But to do both simultaneously? Very difficult.

There is a myth of a fortune at the bottom of the pyramid, according to Toyama. At least, that fortune is purely measured in market size and raw purchasing power. It should not be confused with an opportunity to offer products that alleviate poverty and make a bundle to boot. The rural and even urban poor are difficult markets to serve profitably. A disparate and sometimes non-existent supply chain makes getting products in the hands of consumers a challenge even for the biggest multinationals. Branding products for the poor, or subsidizing them, makes them less appealing to the middle class, who might pay more and create cross-subsidization opportunities (on this point, I think he is wrong, having seen the same solar lanterns we were selling to microfinance clients in the Philippines being sold in malls in Manila for twice the price). Not to mention, selling products to the poor is not going to help them out of poverty. Employment, in the form of manufacturing and labor-intensive work, is the key to growth. In short, it is possible to serve a social cause, and it is possible to make lots of money selling products to the poor. But to do both simultaneously? Very difficult.

It is this biologist’s opinion that Africa is moving from a period of equilibrium toward an evolutionary jump, with technology as the catalyst for systemic change. The paradigm has shifted, and the deep and broad telecom infrastructure has laid the groundwork for a revolution. Africa’s technological evolutionary paradigm will be different. It skipped the land line and went straight to the mobile phone. It skipped the desktop computer and adopted the laptop wholesale instead. The community bank became irrelevant with the creation of

It is this biologist’s opinion that Africa is moving from a period of equilibrium toward an evolutionary jump, with technology as the catalyst for systemic change. The paradigm has shifted, and the deep and broad telecom infrastructure has laid the groundwork for a revolution. Africa’s technological evolutionary paradigm will be different. It skipped the land line and went straight to the mobile phone. It skipped the desktop computer and adopted the laptop wholesale instead. The community bank became irrelevant with the creation of  There are fewer examples of companies and organizations targeting the underlying the issues that lead to systemic change, but the ones that have been successful have changed the world. Mo Ibrahim is a Sudanese-British mobile communications entrepreneur. He founded the company Celtel, a telecommunications company that

There are fewer examples of companies and organizations targeting the underlying the issues that lead to systemic change, but the ones that have been successful have changed the world. Mo Ibrahim is a Sudanese-British mobile communications entrepreneur. He founded the company Celtel, a telecommunications company that  Another game-changing technology is mobile money. In 2007,

Another game-changing technology is mobile money. In 2007,

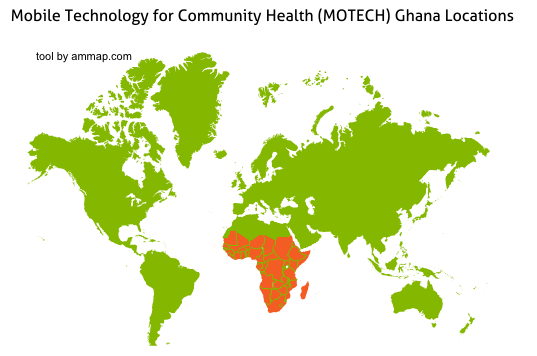

If you are a pregnant woman in the Upper East region of Ghana who has registered with MOTECH, you will receive this message during the fifth week of your pregnancy. Started in 2009, MOTECH is an mHealth platform created in partnership between the Ghana Health Service, Grameen Foundation, and Columbia Mailman Public Health School, with funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. It is designed to facilitate better medical information dissemination to rural areas and improve operational efficiency at community- and district-level health centers in one of the poorest regions of the country.

If you are a pregnant woman in the Upper East region of Ghana who has registered with MOTECH, you will receive this message during the fifth week of your pregnancy. Started in 2009, MOTECH is an mHealth platform created in partnership between the Ghana Health Service, Grameen Foundation, and Columbia Mailman Public Health School, with funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. It is designed to facilitate better medical information dissemination to rural areas and improve operational efficiency at community- and district-level health centers in one of the poorest regions of the country.

I’ve now been in Nairobi for two weeks and have settled in well. I moved into my fairly upscale apartment in Kilimani, a section of Nairobi that is the beating heart of the tech and social enterprise scene here. Up until last Saturday, I was sleeping on a mattress on the floor. The landlord wanted to deliver a new bed frame, so I needed to let the movers into the apartment. It was a total

I’ve now been in Nairobi for two weeks and have settled in well. I moved into my fairly upscale apartment in Kilimani, a section of Nairobi that is the beating heart of the tech and social enterprise scene here. Up until last Saturday, I was sleeping on a mattress on the floor. The landlord wanted to deliver a new bed frame, so I needed to let the movers into the apartment. It was a total  Develop Economies is back after a brief hiatus. I have finished up my work on my current project and am now taking some time to appreciate some of the aspects of Ghana I hadn’t had a chance to enjoy previously. I spent a few days living with a rice farmer about 45 minutes by motorbike from Atsusuare in a small community along a lake fed by the Volta River. I did some work in the field (very minor – I can’t say I’m a great farmer), came across two cobra snakes, and biked an hour each way to the next village with electricity to charge my cell phone and camera. It was the first time I have ever actually experienced rural living, with no electricity, no running water, limited transportation (you have to call a motorbike to pick you from the neighboring town), and the persistent threat of snakebites, malaria, and other calamities that hang around waterlogged fields of paddy rice. I have discussed on this blog the different solutions to the problems of rural energy delivery and distributed power generation, to the problem of inefficiency of burning charcoal and the use of clean-burning cookstoves, and others. But I had never actually seen any of it or experienced it with my own eyes.

Develop Economies is back after a brief hiatus. I have finished up my work on my current project and am now taking some time to appreciate some of the aspects of Ghana I hadn’t had a chance to enjoy previously. I spent a few days living with a rice farmer about 45 minutes by motorbike from Atsusuare in a small community along a lake fed by the Volta River. I did some work in the field (very minor – I can’t say I’m a great farmer), came across two cobra snakes, and biked an hour each way to the next village with electricity to charge my cell phone and camera. It was the first time I have ever actually experienced rural living, with no electricity, no running water, limited transportation (you have to call a motorbike to pick you from the neighboring town), and the persistent threat of snakebites, malaria, and other calamities that hang around waterlogged fields of paddy rice. I have discussed on this blog the different solutions to the problems of rural energy delivery and distributed power generation, to the problem of inefficiency of burning charcoal and the use of clean-burning cookstoves, and others. But I had never actually seen any of it or experienced it with my own eyes.