The book review in the Wall Street Journal this morning discusses the Robert Guest book, Borderless Economics, which details how global labor movement increases trade, informational flow, communication, and technology. The topic of migration has been making the rounds, partly due to book reviews of Borderless Economics in all the major journals and magazines, but also because the time is right for a frank discussion about the realities of a global economy.

The book review in the Wall Street Journal this morning discusses the Robert Guest book, Borderless Economics, which details how global labor movement increases trade, informational flow, communication, and technology. The topic of migration has been making the rounds, partly due to book reviews of Borderless Economics in all the major journals and magazines, but also because the time is right for a frank discussion about the realities of a global economy.

Develop Economies agrees with all of Guest’s points. The economic benefits are vast. With engineers and PhDs from abroad and a more nimble, low-cost workforce comprised of unskilled immigrant labor, the United States can compete for first place in the global economy. Without it, we might be battling for second place. But, in this post, I want to discuss the role of Diasporas in preventing conflict and promoting economic development.

The world would be a better place if international movement and migration were more fluid. One of the reasons that Ghana is considered to be one of the successful democracies in Africa, while Kenya deals with upheavals every few years and corruption scandals every day, is that an internal diaspora through the country over the last half-century led to a blurring of tribal boundaries. Both countries have dozens of tribes, each with its own language. But, while Kenyans, as a generalization, maintain strong ties to their familial home and typically marry within the tribe, Ghanaians intermarry and bring the entire family with them when they move. “That’s why we are so peaceful,” one coworker told me. “We all marry each other!” (This is also one reason why mobile money is pervasive in Kenya, but not Ghana – but that is for another post.)

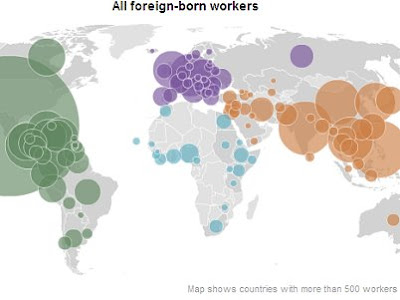

Now imagine that dynamic on a global scale. Heterogeneous and multi-ethnic societies are less likely to adopt a herd mentality, because cultural exchange promotes empathy. This, to me, is why the United States is probably the most integrated and least bigoted country in the world (seriously). I am always amazed when I come back to the U.S. and look around the airport to see people of every color speaking different languages. And, from a numbers perspective, it makes sense:

Mr. Guest concludes with the argument that, thanks to America’s immigrants, the U.S. is likely to remain for decades the richest and most powerful nation in the world. America has the largest foreign-born population by far—an astonishing 43 million people, 10 million more than the entire population of Canada. China, by contrast, has a foreign-born population of less than one million.

From an economic standpoint, Diasporas create global trade networks that move money and products around the world for a fraction of the cost it might cost otherwise. I saw it in the Philippines, where the richest family in the country is Chinese, and West Africa, where the Lebanese control rice importation, and in East Africa, where the Indians control just about everything. With greater economic integration, the cost of conflict increases drastically for both nations. Create enough cross-border migration and trade, and the lines begin to blur completely.

Infographic from the Economist

In the WSJ article, specifically, the author examines the point purely from an international development perspective. The author, Katherine Mangu-Ward, editor of Reason magazine, discusses the economic benefits, compared with foreign aid:

Infographic from the New York Times

‘As a tool for spreading wealth, open borders make foreign aid look like a child’s lemonade stand,” writes Robert Guest, business editor of the Economist, in “Borderless Economics,” a rapid-fire case for the free movement of labor from one country to another. [Economist Lant] Pritchett found that if developed countries slightly liberalized their immigration laws and increased their work forces by a mere 3%, the gains in remittances and other benefits to developing countries would amount to more than $300 billion.

Put another way, a Salvadorean man with a high-school education needs only to come to the U.S. to increase his annual earning power more than eightfold, from $2,700 to $22,611—a figure, by the way, almost identical to the earning potential for Americans with the same level of education. Compare the $300 billion benefit with the $70 billion spent annually on foreign aid by developed countries, much of which ends up in the Swiss bank accounts of corrupt politicians.

Sing it from the rooftops

I couldn’t agree more. But I do have to address one point at the end of the article, in which the author feels the need to take down microfinance:

It is galling to Mr. Guest that many well-meaning people are more invested in promoting ideas like Third World microcredit than in clamoring for easier immigration. Lant Pritchett, the former World Bank economist, shares Mr. Guest’s skepticism about the importance of the much ballyhooed microloans that help the world’s poorest people to buy livestock or open a small business. The concept was pioneered by Muhammad Yunus, the founder of Grameen Bank in Bangladesh and winner of the 2006 Nobel Peace Prize. Mr. Pritchett tells the author that the average gain for a Bangladeshi from a lifetime of these loans is about the same as the earnings from working just eight weeks in America. “If I get 3,000 Bangladeshi workers into the U.S.,” Mr. Pritchett wonders, “do I get the Nobel Peace Prize?” No, but with luck Mr. Guest’s argument in “Borderless Economics” will be rewarded with serious attention in the places that count.

This is unnecessary. Whether or not that Bangladeshi will make more in those eight weeks is completely irrelevant if he never has the chance to go to the United States. I think that all countries should have freer trade agreement, reduce tariffs, and eliminate ethanol and farm subsidies. That would certainly be more effective than the most successful anti-poverty strategies in lifting hundreds of millions of people above the poverty line. Unfortunately, it will never happen. Because supporting the elimination of tariffs, like open borders, is political suicide. And, like most policies supported by purist Libertarians, it will never happen.

So, in the meantime, microcredit is doing something to fill the gap. I am sure that the Bangladeshi would prefer that to waiting for his visa to the United States to process. If Pritchett can make that happen for even ten poor Bangladeshis, then he should get the Nobel Prize.

Develop Economies’ Music Recommendation

There is a fierce debate going on right now in India about a new piece of legislation that that will allow multi-national corporations to operate as joint ventures in the country, owning up to 51%. And a week ago, the Indian government backtracked and announced that it would not pass the legislation after all. It is worth examining the potential pros and cons.

There is a fierce debate going on right now in India about a new piece of legislation that that will allow multi-national corporations to operate as joint ventures in the country, owning up to 51%. And a week ago, the Indian government backtracked and announced that it would not pass the legislation after all. It is worth examining the potential pros and cons.