“It is simply a fact that our social problems are increasingly connected to the depravity of the poor. If an American works hard, completes their education, gets married, and stays married, then they will rarely — very rarely — be poor. At the same time, poverty is the handmaiden of illegitimacy, divorce, ignorance, and addiction. As we have poured money into welfare, we’ve done nothing to address the behaviors that lead to poverty while doing all we can to make that poverty more comfortable and sustainable.”

David French, Bigot

Believe it or not, somebody wrote that. Enough people have pointed out that David French, the author, confuses correlation with causality. Here is one argument from Seth Masket that sufficiently debunks the theory:

[T]hese key things — education, a successful marriage, and a job — are a lot easier to come by if you’re not poor. What’s more, they’re a lot easier to come by if your parents weren’t poor. But just being born into a poor home means a person is going to have a much harder time coming by these key things that keep him or her out of poverty. That doesn’t make the person depraved. It makes the person a victim of circumstances.

Here is another one from Matt Yglesias:

Now I suppose you could argue that the availability of drug treatment programs, battered women’s shelters, and food kitchens creates “moral hazard” and encourages people to become heroin addicts and/or bed down with abusive partners. But I don’t think that this is a very plausible story. People don’t become homeless drug addicts because the downside to being a homeless drug addict isn’t severe enough in the contemporary United States. And affluent parents don’t treat their children in this kind of punitive way. If a prosperous teenager develops an addiction problem, he’ll be given help. Any halfway responsible parent with the means to do so would bail out a daughter whose live-in boyfriend is abusing her. Poor people have, typically, made some mistakes in life and it’s often the case that had they lived lives free of error, they wouldn’t be poor. But it’s not like middle class people are living mistake-free lives. The difference is that middle class people have lives that give them a fair margin for error, whereas people who start out in bad circumstances can be crippled by a bit of misfortune, impulsiveness, or bad decision-making.

Arguing with someone like French would be like laying out all the factual reasons why a mountain is in the wrong pace, not to mention it sounds like he has the intellectual rigor of an inanimate piece of rock. But I ruminated on other aspects of why French is wrong (beyond the obvious), and came up with a few clear examples from my own life.

David French's personal heroes, the Dukes.

In most aspects of my life, I’ve been pretty fortunate. My parents are physicians who put a lot of emphasis on education. I spent most of my high school years grounded due to some harmless hijinks, and took a lot of AP classes because my parents pushed my brother and I to excel in school. I went to a good university, where I was surrounded by smart people and educational resources that I wish I could still access. After I graduated, I went to work for a company in Boston under smart people with graduate degrees from Harvard and MIT. At Kiva and Technoserve, my friends and coworkers came from diverse backgrounds, and had the resources (financial and otherwise) to volunteer for a few months. Now, in Nairobi, I live with a group of tech entrepreneurs and interact on a daily basis with some of the smartest people I’ve ever met.

All this is meant to stress the impact people have in your life. From the start, I was on a track that, at every turn, placed me in the midst of mentors who have shaped my intellectual and personal growth. My teachers in high school and college were committed and enthusiastic. My bosses and mentors are skilled and talented. I spoke with one of my old managers tonight after about two years to get some career and school advice. I’m grateful to have opportunities like that, but I hold no illusions about the role my own favorable circumstances played in providing them.

Conversely, without those role models, you need to have a superhuman combination of motivation, maturity, and intelligence at a very young age to see the benefits of education and hard work. And even if you do, there is no guarantee that an education is going to make your situation that much better (and in today’s America, with income inequality at its highest levels in 70 years, that is increasingly true). One of the great paradoxes of education in countries with chronic high unemployment is that the economic returns to schooling are marginal when there are no jobs to absorb all the graduates. Does that make people who pull their kids from school “depraved”? Of course not. As Masket says, they are a victim of circumstances. In fact, from an economic and financial perspective, they are thinking rationally, which, as someone who believes that the God and the Free Market are the only paths to salvation, should appreciate. Of course French is one of a great many thinkers today who have cobbled together all of the

Conversely, without those role models, you need to have a superhuman combination of motivation, maturity, and intelligence at a very young age to see the benefits of education and hard work. And even if you do, there is no guarantee that an education is going to make your situation that much better (and in today’s America, with income inequality at its highest levels in 70 years, that is increasingly true). One of the great paradoxes of education in countries with chronic high unemployment is that the economic returns to schooling are marginal when there are no jobs to absorb all the graduates. Does that make people who pull their kids from school “depraved”? Of course not. As Masket says, they are a victim of circumstances. In fact, from an economic and financial perspective, they are thinking rationally, which, as someone who believes that the God and the Free Market are the only paths to salvation, should appreciate. Of course French is one of a great many thinkers today who have cobbled together all of the

People like French don’t actually really understand their own principles, and would probably be surprised to hear that the two most influential figures in developing their worldview – Ayn Rand and Jesus – would both strongly disagree with their stance on just about everything. Take the last two paragraphs of French’s article on the National Review blog:

Earlier this week, Walter Russell Mead highlighted disturbing research showing that the poor — far more than the rich — are disconnected from church and religion. While church attendance is dropping among all social classes, it’s falling off a cliff for the poorest and least-educated Americans. In other words, the deeper a person slides into poverty, the more they’re disconnected from the very values that can save them and their families.

The bottom line is that we need more free enterprise, and we need more virtue. Sadly, the Great Society and the sexual revolution have deprived us of both.

The key to ending poverty, despite the growing concentration of wealth at the top, is God and the markets. Of course, Ayn Rand, the intellectual figurehead of the kind of laissez-faire economics advocated by French, was a devout Atheist. I’ve read Atlas Shrugged and The Fountainhead, my “Introduction to Philosophy” professor was the editor of the Ayn Rand Reader, and my father would like to think himself an objectivist, but he cares about people too much to truly commit. These, I think, are enough to establish my bona fides. In her own words:

There has never been a philosophy, a theory or a doctrine, that attacked (or ‘limited’) reason, which did not preach submission to the power of some authority.

So now that we have kicked out one of French’s legs, let’s go for the other one: religion. I did a quick Google search for “Jesus poverty quotes” and it returned 7.3 million views. This one from Deuteronomy 15:7, 11 makes my point sufficiently:

If there is a poor man among your brothers in any of the towns of the land that the LORD your God is giving you, do not be hardhearted or tightfisted toward your poor brother. There will always be poor people in the land. Therefore I command you to be openhanded toward your brothers and toward the poor and needy in your land.

Were Jesus to return to earth today and come face-to-face with David French, do you think he would say, “You’re absolutely right, Dave – the poor are depraved.” I supposed that French would say that the Levites weren’t welfare queens.

David French is either an ostrich clinging to a romanticized version of the American dream, an idiot, or both. In this country more than many others around the world, if you work hard, you can be successful. But to posit that everyone in this world is dealt the same hand and the ones currently earning less than $40K a year to provide for a family of four have simply chosen a life of “depravity” is ludicrous. Remember Dave – that kind of thinking will get you left behind.

DEVELOP ECONOMIES’ MUSIC RECOMMENDATION

One sign that the U.S. political scene has reached rock bottom is David Brooks writing one of his weekly columns about development workers in Nairobi. In “

One sign that the U.S. political scene has reached rock bottom is David Brooks writing one of his weekly columns about development workers in Nairobi. In “ A friend posted an article on his Facebook wall titled “

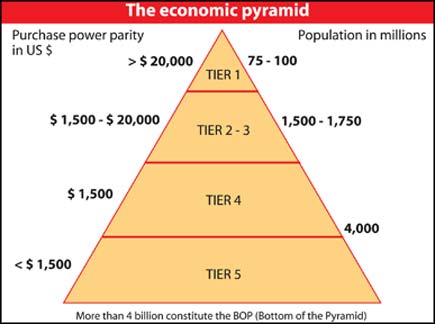

A friend posted an article on his Facebook wall titled “ There is a myth of a fortune at the bottom of the pyramid, according to Toyama. At least, that fortune is purely measured in market size and raw purchasing power. It should not be confused with an opportunity to offer products that alleviate poverty and make a bundle to boot. The rural and even urban poor are difficult markets to serve profitably. A disparate and sometimes non-existent supply chain makes getting products in the hands of consumers a challenge even for the biggest multinationals. Branding products for the poor, or subsidizing them, makes them less appealing to the middle class, who might pay more and create cross-subsidization opportunities (on this point, I think he is wrong, having seen the same solar lanterns we were selling to microfinance clients in the Philippines being sold in malls in Manila for twice the price). Not to mention, selling products to the poor is not going to help them out of poverty. Employment, in the form of manufacturing and labor-intensive work, is the key to growth. In short, it is possible to serve a social cause, and it is possible to make lots of money selling products to the poor. But to do both simultaneously? Very difficult.

There is a myth of a fortune at the bottom of the pyramid, according to Toyama. At least, that fortune is purely measured in market size and raw purchasing power. It should not be confused with an opportunity to offer products that alleviate poverty and make a bundle to boot. The rural and even urban poor are difficult markets to serve profitably. A disparate and sometimes non-existent supply chain makes getting products in the hands of consumers a challenge even for the biggest multinationals. Branding products for the poor, or subsidizing them, makes them less appealing to the middle class, who might pay more and create cross-subsidization opportunities (on this point, I think he is wrong, having seen the same solar lanterns we were selling to microfinance clients in the Philippines being sold in malls in Manila for twice the price). Not to mention, selling products to the poor is not going to help them out of poverty. Employment, in the form of manufacturing and labor-intensive work, is the key to growth. In short, it is possible to serve a social cause, and it is possible to make lots of money selling products to the poor. But to do both simultaneously? Very difficult.

The following is a guest post from Mark Brown, an agriculture value chains specialist with Engineers Without Borders Canada working in Ghana. The post originally appeared on EWB’s blog,

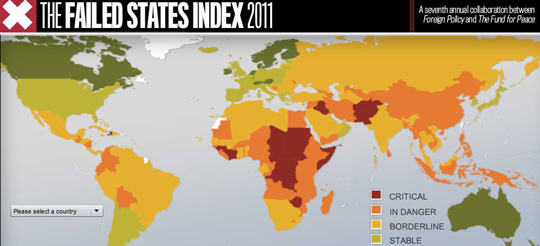

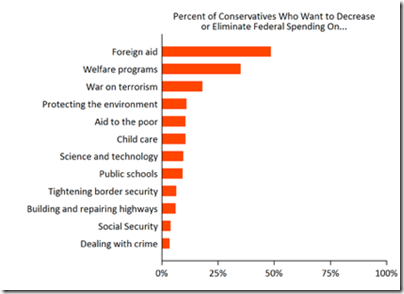

The following is a guest post from Mark Brown, an agriculture value chains specialist with Engineers Without Borders Canada working in Ghana. The post originally appeared on EWB’s blog,  So why don’t Americans care about foreign aid? When asked to prioritize what they would cut from the budget, foreign aid is always number one. People assume that our foreign aid budget is ten times larger than its actually size (about 1%). I think there are a lot of reasons why Americans don’t care about famine, or, more broadly, foreign aid in general (clearly Americans care about famine, but I define “caring” as making a concerted sacrifice toward its elimination). Here are a few that come to mind:

So why don’t Americans care about foreign aid? When asked to prioritize what they would cut from the budget, foreign aid is always number one. People assume that our foreign aid budget is ten times larger than its actually size (about 1%). I think there are a lot of reasons why Americans don’t care about famine, or, more broadly, foreign aid in general (clearly Americans care about famine, but I define “caring” as making a concerted sacrifice toward its elimination). Here are a few that come to mind: