One of Somalia's many problems. (AFP Photo/Mohamed Dahir)

I’ve been reading a lot of opinions lately about the decline of the empire of the United States, where experts try to pinpoint the exact moment where we planted our flag atop the hill of global dominance and then began our descent down the other side (somewhere around the early 1990’s, according to the consensus). In every calculation, the war in Afghanistan is either emblematic of a state in decline (they don’t call it the “graveyard of empires” for nothing) or something that actually precipitated the fall. We defeated the communists at the end of the 1980’s – the high-water mark in our global position. And one of the great ironies of that victory is that we secretly funded the mujahedeen in Afghanistan to fight the Soviet Union and, in doing so, kept the Russians mired in the same position we have found ourselves over the last ten years. One of those mujahedeen was Osama Bin Laden, son of a Saudi billionaire who, with the help of the CIA, bankrolled the insurgency against the Soviets. Bin Laden quickly turned against the United States (not that he was ever with the U.S.) and became the figurehead of the global jihadist movement until a few months ago when Barack Obama killed him.

People love to point out the fact that we funded the very people who have tried to kill us over the last two decades. How could we do that, they ask? The answer is relatively simple. When a country doesn’t seem like a threat, no one really pays cares if we are potentially nurturing our future enemies, so long as we are able to channel them in support of our cause at the time. And then, when the snake is all grown up, he bites. And, in an ironic twist that would make George Santyana roll over in his grave we are doing it again. Only this time, we are doing it in Somalia, the last truly failed state.

Ever-present Somalia.

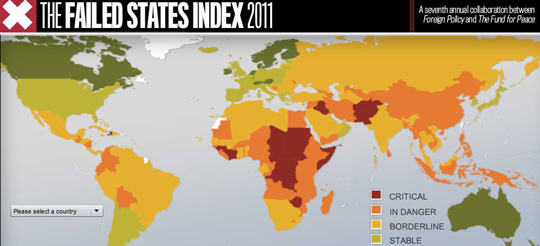

It makes sense at this point to give some context about Somalia. With a score of 113.6, it is consistently ranked number one on Foreign Policy magazine’s Failed States Index year after year. Here is how it is described in the most recent ranking:

Relatively speaking, the first months of 2011 have been full of good news for Somalia, the world’s closest approximation of anarchy. For two full decades, the majority of the territory in this crescent-shaped country on the Horn of Africa has gone essentially ungoverned; an internationally recognized transitional government is fighting tooth and nail to control the capital. Yet after months of stalemate with Islamist insurgents, the momentum finally seems to be turning. Block by block, the national troops — with the considerable help of an African Union-U.N. joint peacekeeping mission — have made significant territorial gains in Mogadishu.

Yet Somalia is still in tatters. Out of a population of nearly 10 million, as many as 3 million are thought to need humanitarian assistance. Another 2 million have been uprooted in the conflict, and political infighting has paralyzed the nascent government. Neighboring Uganda has warned that the fractures stand to make matters worse, offering Islamist insurgent groups a chance to reorganize.

Perhaps the greatest fear looming over Somalia today is that it will become the next haven for al Qaeda fleeing Afghanistan. Somalia’s Islamist rebels, who call themselves al-Shabab, have already pledged their allegiance to the global terrorist network.

Here, demonstrators in Mogadishu denounce the United Nations mission in the country, accusing it of spending too much on flying diplomats in and out of Nairobi and not enough on fixing what’s broken in Somalia.

This was written prior to the recent famine, which has left over 30,000 children dead and is the localized food crisis in 20 years. How to deal with the “basketcase” of Somalia has eluded successive U.S. governments for the last several decades. Now, as the U.S. is faced with the prospect of Somalia becoming the next Afghanistan – a hub for global jihadist groups like Al-Qaeda – the issue has suddenly become much more pressing. Jeffrey Gettlemen, the failed-state beat reporter for the New York Times, reports on the latest use of military contractors to fight Al-Shabab, the Islamic Fundamentalist group that only a mother could love:

The Pentagon has recently told Congress that it plans to send nearly $45 million worth of military equipment to bolster the Ugandan and Burundian troops. The arms package includes transport trucks, body armor, night vision goggles and even four small drone aircraft that the African troops can use to spy on Shabab positions.

Unlike regular Somali government troops, the C.I.A.-trained Somali commandos are outfitted with new weapons and flak jackets, and are given sunglasses and ski masks to conceal their identities. They are part of the Somali National Security Agency — an intelligence organization financed largely by the C.I.A. — which answers to Somalia’s Transitional Federal Government. Many in Mogadishu, though, believe that the Somali intelligence service is building a power base independent of the weak government.

One Somali official, speaking only on the condition of anonymity, said that the spy service was becoming a “government within a government.”

“No one, not even the president, knows what the N.S.A. is doing,” he said. “The Americans are creating a monster.”

The future of global jihad.

I have a great respect for the complexities of foreign policy, containment, defense, and dealing with a king cobra like Somalia. But the African Union should be dealing with Somalia and taking responsibility of policing its own region. Having a major presence there creates resentment in the same way that it has done Afghanistan. It is a dangerous country and to allow it to effectively fall apart is not really an option either. So I understand why these measures might need to be taken. Still, I suppose this is how it starts.

Towards the end of the article there is another nugget of insight into the different ways of approaching a failed state with an Islamic fundamentalist problem:

In Washington, American officials said debates were under way about just how much the United States should rely on clandestine militia training and armed drone strikes to fight the Shabab. Over the past year, the American Embassy in Nairobi, according to one American official, has become a hive of military and intelligence operatives who are “chomping at the bit” to escalate operations in Somalia. But Mr. Carson, the State Department official, has opposed the drone strikes because of the risk of turning more Somalis toward the Shabab, according to several officials.

Johnnie Carson is the highest state department official in Africa. He is a career foreign service officer, and has cut his diplomatic teeth dealing with African governments since the 1970s. By all accounts, he understands the cultural nuances that affect diplomacy in sub-Saharan Africa. Reading this, I appreciate that someone like Carson is running the show.

I think that this sort of measured approach to dealing with a volatile and complex situation is reflective of Obama’s deliberative foreign policy. Brute military force that rains collateral damage on civilians makes for fertile recruiting grounds for Jihadist groups. It needs to be smartly applied, in combination with diplomacy and development. But, as I wrote the other day, the latter two could end up on the receiving end of cuts at the end of 2012. If that happens, the counterforce pushing back on the military operatives itching to put boots on the ground in Somalia will be marginalized. And history may be free to repeat itself.