Learning to read in Burma.

The photo on the header of this blog was taken in Bagan, a city in the center of Burma that is home to thousands of ornate Buddhist temples. I was sitting atop another of the thousand temples that litter the skyline, wondering how such a stunning place could have so few visitors. The temples in Bagan are relics of a once-prosperous society. Today, the country appears frozen in time, its potential ruined by a repressive military government that has left Burma in a developmental stasis for the last thirty years.

The strategic geography of Burma is undeniable.

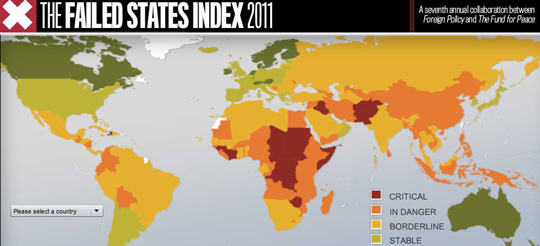

But all of that is changing now. Traditionally, the West has always viewed Burma as a basketcase – a country rich in natural resources beset by post-colonial woes and chock full of human rights violations. Despite its hideous record of government and poor economic growth, Burma has always had a few things going for it. First, it has a wealth of natural resources. Diamonds, natural gas, oil, etc. Second, it is strategically located between two of the fastest-growing economies in the world, China and India. Combined, China and India make up a third of the world population and are contributing an increasing percentage of the global GDP. When speaking about the future of geopolitics and the world economy, these two countries are increasingly part of the conversation. And Burma, the basketcase of East Asia, sits conveniently between these two rising giants. Given that Russia lies further north, and Brazil dominates the Americas south of the Equator, Burma holds the distinction of being the only country in the world to sit directly in between two of the BRIC countries.

It makes sense that China and India would want to facilitate trade as efficiently and cheaply as possible. To do that, only one thing stands in the way: Burma. Given the Chinese government’s track record of long-term strategic thinking when it comes to developing its future trading partners, China has taken an active role in building up the infrastructure in a future vital trading partner. On Burma’s western front, India is taking a similarly proactive approach in making sure it takes advantage of the country’s location and resources. And, amazingly, it sounds like it could be a win-win-win situation:

A Hindu rite of passage. Day one in Burma

Watching these developments, some have warned of a new Great Game, leading to conflict between the world’s largest emerging powers. But others predict instead the making of a new Silk Road, like the one in ancient and medieval times that coupled China to Central Asia and Europe. It’s important to remember that this geographic shift comes at a very special moment in Asia’s history: a moment of growing peace and prosperity at the conclusion of a century of tremendous violence and armed conflict and centuries more of Western colonial domination. The happier scenario is far from impossible.

The generation now coming of age is the first to grow up in an Asia that is both post-colonial and (with a few small exceptions) postwar. New rivalries may yet fuel 21st-century nationalisms and lead to a new Great Game, but there is great optimism nearly everywhere, at least among the middle classes and the elites that drive policy: a sense that history is on Asia’s side and a desire to focus on future wealth, not hark back to the dark times that have only recently been left behind.

And a crossroads through Burma would not be a simple joining up of countries. The parts of China and India that are being drawn together over Burma are among the most far-flung parts of the two giant states, regions of unparalleled ethnic and linguistic diversity where people speak literally hundreds of mutually unintelligible languages, of forgotten kingdoms like Manipur and Dali, and of isolated upland societies that were, until recently, beyond the control of Delhi or Beijing. They are also places where ballooning populations have only now filled out a once very sparsely peopled and densely forested landscape. New countries are finding new neighbors. Whereas the fall of the Berlin Wall reopened contacts that had only temporarily been suspended, the transformations under way are enabling entirely new encounters. There is the possibility of a cosmopolitan nexus at the heart of Asia.

Readers of this blog know that I have a soft spot in my heart for Burma and its struggle. I’ve often ruminated on whether anything good would ever befall the Burmese people. But now, with two of the four BRIC countries looking to one another for a mutually-beneficial partnership in the post-American world, things are finally looking up.

Trekking to Inle Lake

I will close with a long paragraph from the Foreign Policy article quoted above that speaks to the optimism in the Far East:

A new friend.

It’s a fragile opening. The president seems determined to push ahead, but his is not the only voice. There are other powerful ex-generals in parliament and in the cabinet, and the structures of repression remain intact. Burma is at a critical turning point.

And now, for the first time, Burma’s politics matter beyond its immediate borders. If this opportunity for positive change is lost, Burma may remain a miserably run place — but it will no longer be an isolated backwater. The great infrastructure projects under way will continue, as will the much longer-term processes of change. Asia’s frontier will close and a new but dangerous crossroads will be the result.

But if Burma indeed takes a turn for the better and we see an end to decades of armed conflict, a lifting of Western sanctions, democratic government, and broad-based economic growth, the impact could be dramatic. China’s hinterland will suddenly border a vibrant and young democracy, and India’s northeast will be transformed from a dead end into its bridge to the Far East. What happens next in Burma could be a game-changer for all Asia.

As it turns out, rather than sanctions and a tourism boycott, simple economics might be just what Burma needs to become a vibrant democracy after decades of brutal military rule. I will look forward to going back.

Here are a few of my favorite pictures from this amazing place. The photos were taken by my friend, Gemma North, a fellow Kiva Fellow in Cambodia.

My first trip to the Kingdom