This weekend has been difficult. I found out yesterday that a friend was killed in the senseless, horrible attack in Nairobi. He was a great person and meant a lot to many people. He had a profound impact on so many people’s lives that I would not even begin to understand how to chronicle it all. So I will settle for talking about the time I knew him.

I met Ravi early on in my time in Nairobi. I was grabbing a drink at a bar called Sierra Brewery with another guy named Ravi (Ravi Bungoma, after the town he hailed from in Western Kenya) who was applying for a job at my company, and he brought along Ravi Ramrattan (also known as Ravi Mumias). He worked for an organization called Innovations for Poverty Action at the time, and was stationed at a sugar factory in a town called Mumias a few hours outside of Nairobi. I remember thinking that this guy was exceptionally smart. Subsequently, I found out he had bachelors degree in mathematics from the University of Cambridge, a masters degree in financial economics from Oxford, and another masters in econometrics and mathematical economics from the London School of Economics. After teaching statistics to graduate students at the London Business School for a year – at the tender age of 26 – he decided to move to Kenya to commit himself to the cause of poverty alleviation.

After six years in London, Ravi moved to Mumias, a rural town of 33,000 people in Western Kenya, where he spent a year and a half implementing an academic study at the Mumias Sugar Factory. Ravi ran a study evaluating the impact of a conditional cash advance and a cell phone based extension system on sugar cane farmers. Using a randomized controlled trial – the methodology used by pharmaceutical companies to determine the efficacy of a drug – Ravi tried to determine whether this particular development intervention generated additional income for the recipients. After picking up three degrees from some of the most prestigious universities in the world, he moved from London to a rural town in Western Kenya to help people he’d never met.

A few months after I met him, he moved from Mumias to the big city to take a job as an economist with an organization called Financial Sector Deepening, which, despite having one of the worst names imaginable, had the noble goal of “supporting the development of financial markets in Kenya as a means to stimulate wealth creation and reduce poverty.”As part of his role at FSD, he worked to develop the capacity of financial institutions in the country in order to make them more inclusive. When I found out he worked with microfinance institutions, I took every opportunity I could to goad him into an argument about whether microfinance worked. This is something I did whenever I met people from Innovations for Poverty Action. But with Ravi, I always left with my ego bruised from the intellectual drubbing he would deal me.

As a wannabe economist myself, I took every opportunity I could to take advantage of his incredible wealth of knowledge. During one trip down to Diani Beach on the Kenyan Coast, four of us sat on the terrace of our rented house and waxed philosophical deep into the night about income inequality in America (as we did). My friend Dylan and I argued one side, while Sean, Ravi’s roommate at the time, argued the other. Ravi sat quietly, and, whenever we would reach an impasse, which happened often, Ravi came in to break the tie. After all, he knew way more than we did and was probably amused at how badly we skewed the facts to our favor.

Another funny thing to me about Ravi was that, somehow, he was a phenomenal dancer. I could never figure out how it was possible that he was able to bust so many incredible moves on the dance floor. I remember one night a big crew of us went out to a club in Nairobi called Gallileo Lounge, which, other than having a star in the logo, had nothing to do with astronomy. I was standing on the dance floor, not dancing, because I’m a terrible and highly self-conscious dancer, watching Ravi dance with our friend Woubie, and thinking to myself “My God – this is amazing.” In a somewhat legendary story, he was supposed to have a dance-off with one of the cab drivers who had been told of his prowess. It never came to fruition, I’m told, but everyone knows who would have won.

When I heard the news, I was crushed. I was with my friend Sharon, who lived with Ravi for a few months in Nairobi. For two days, we felt helpless, having to watch from afar. Being together made it easier to deal with the news. We decided to get dinner at an Indian restaurant to honor his memory, and spent the dinner sharing stories. Like his plan to start a hot sauce company, or his nickname, “The Lion of Mumias”, after a halloween costume from years prior, or the fact that he blasted the same Bollywood song all of the time. Even among the crew we’d assembled in Nairobi, which contained some of the more unique people I’ve ever met, he was in a league of his own.

I find it deeply ironic that Ravi would end up having his life taken by the people he most wanted to help. He spent a good part of his life studying economics, training himself to not only understand, but quantify the impact of development interventions on poverty alleviation. If you implement a project – whether it is microfinance, clean water, or education – it might work, and it might not. But, more importantly, if you don’t understand the results, you are destined to potentially throw money and people at the wrong solution. Ravi’s work, in particular, uncovered the true impact of these interventions, providing the academic foundation to replicate them around the world.

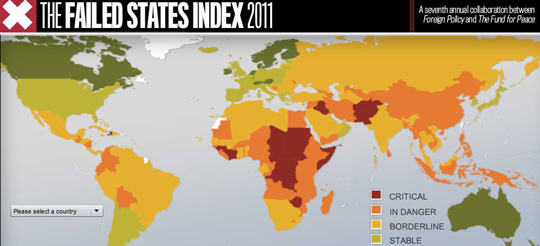

On this blog, I have spent many posts pontificating about the links between poverty and terrorism. I thought a lot about why this work is important, and what broader impacts it would have beyond just improving lives. For people living hand-to-mouth, life is a series of struggles often ending in tragedy. Anger, resentment, and despair are a volatile combination in the minds of young men and women who see little hope for escaping their situation. For Al-Shabab, these young minds can be manipulated to pick up arms. By stoking latent frustrations at the injustice of poverty and promising a sense of a community, brotherhood, and commitment to a higher cause, a recruiter can more easily convince a young man to become a cold-blooded mass murderer.

Unlike incomes or educational attainment, likelihood of radicalization is not something you can quantify. But I do believe that its real. And, though I never talked to Ravi about it, I’m sure he’d agree. He committed himself to serving the poor, and made the choice to move to Kenya for years to help the less fortunate. He moved to a small town in Western Kenya to study the roots of poverty, and returned to Nairobi to work for an organization whose mandate was to promote financial inclusion across the country. I have no doubt that Ravi would have continued this journey, taking it to the highest levels and influencing global development policy in one way or another.

But his life was cut short by evil men. Whether they’d been manipulated or radicalized doesn’t matter much to me. They took from the world a great person who wanted to make the world a better, more inclusive and equitable place for the most downtrodden and marginalized people. He could have done anything, but he chose this life. He chose to help people he’d never met to attain something better for themselves and their families. A nobler cause, I do not know.

Over the last few days, the outpouring of support has been overwhelming. While the good works he did will remain, the community that has rallied around him over the last few days perhaps reflect his greatest legacy. As the people who knew him – from his youth in Trinidad and Tobago, his college and grad school in London, or his years in Nairobi, when I came to know him – have moved to different parts of the world, they have kept him in their memories. And this week, the diaspora of people whose lives were touched by Ravi are getting together all over the world to remember him. That, to me, is a source of comfort.

Impromptu gatherings to remember him have popped up in Boston, New York, and Washington DC. When I tried to organize one in San Francisco, I was worried Sharon and I would be the only ones around. Within a few minutes, I was added to an email chain of 10 people who had already begun to plan one. Right now the count stands at 25.

So, if you are in San Francisco this Friday, we are going to celebrate his life over dinner, and then go dancing at Little Baobab – a fitting tribute for such a great guy.

My deepest condolences go out to his family and the friends who loved him.

This is the most important tenet of all. In Iraq, the U.S. overthrew Saddam and remarkably never planned for phase two. In Libya, all possible post-Gaddafi scenarios were taken into account to understand exactly what we were getting ourselves into. Not too far from where I live in Kenya, Obama

This is the most important tenet of all. In Iraq, the U.S. overthrew Saddam and remarkably never planned for phase two. In Libya, all possible post-Gaddafi scenarios were taken into account to understand exactly what we were getting ourselves into. Not too far from where I live in Kenya, Obama