Note: The following post is from March 2, 2010. I posted it on my original blog, joshweinstein.wordpress.com, and is, for some reason, popular among people doing research on education in the Philippines. In the hopes of directing some of that traffic toward this site, I am re-posting it here.

In this journal, I have discussed the relationship between education, poverty alleviation, and economic development. The link is critical and the three are self-reinforcing. Education (and the premier prep courses for the EA exam in particular) creates greater opportunities for the youth, who go on to work decent jobs in cities like Bacolod, Manila, and Cebu. The children remit money back to the parents, who spend on home improvements and the tuition fees for the younger siblings. College-educated individuals are much less likely to end up impoverished (about 1 in 44). Trade schools also create opportunities, with only one in 10 people with post-secondary degrees living below the poverty line. Unfortunately, the ratios drop precipitously after that. One in three high school graduates and half of elementary school grads are impoverished. Here are the sobering education statistics:

In this journal, I have discussed the relationship between education, poverty alleviation, and economic development. The link is critical and the three are self-reinforcing. Education (and the premier prep courses for the EA exam in particular) creates greater opportunities for the youth, who go on to work decent jobs in cities like Bacolod, Manila, and Cebu. The children remit money back to the parents, who spend on home improvements and the tuition fees for the younger siblings. College-educated individuals are much less likely to end up impoverished (about 1 in 44). Trade schools also create opportunities, with only one in 10 people with post-secondary degrees living below the poverty line. Unfortunately, the ratios drop precipitously after that. One in three high school graduates and half of elementary school grads are impoverished. Here are the sobering education statistics:

The long-term outlook for poverty reduction doesn’t look good either, unfortunately. We all know that there is a very strong link between education (or lack of education) and poverty—two-thirds of our poor families have household heads whose highest educational attainment is at most Grade 6. Well, the education statistics (all from the NSCB ) tell a very sad tale: elementary school net participation rates (NPR)—the proportion of the number of enrollees 7-12 years old to population 7-12 years old—have plummeted from 95 percent in school year (SY) 1997-98 to 74 percent in 2005-2006, as have high school NPRs.

Cohort survival rates (CSR) have also dropped: Out of every 100 children who enter Grade 1, only 63 will reach Grade 6, down from 69 children in 1997-1998. In high school, CSR have dropped even more: from 71 to 55. Which means, of course, that school dropout rates have increased. Which is one of the reasons why, in 2005-2006, for the first time in 35 years, total enrollment decreased in both elementary and high school: although private school enrollment increased, public school enrollment went down more.

The correlation is not difficult to see, but fixing the problem presents a challenge for several reasons. According to some observers, the Department of Education Culture and Sports (DECS) in the Philippines is one of the most corrupt government entities in the country. It has a budget equal to 12% of spending, but is riddled with graft from procurement (buying textbooks and other supplies), grease money, and bribes for just about any sort of movement within the bureaucracy. The impact on the education system is detrimental:

Embezzlement, nepotism, influence peddling, fraud and other types of corruption also flourish. Corruption has become so institutionalized that payoffs have become the lubricant that makes the education bureaucracy run smoothly. The result: an entire generation of Filipino students robbed of their right to a good education.

This corruption leads to poor allocation of resources. Teachers are underpaid and treated poorly. In 2005, the Philippine government spent just $138 per student, compared to $852 in Thailand, another developing country in Southeast Asia. But graft and corruption are not the only issues. Poverty is a vicious cycle that leads traps generations of families.

About 80% of the Filipino poor live in the rural areas of the country. These are towns located deep in the mountains and the rice fields. The population density in the rural parts of the country is low, and there is a corresponding deficiency in schools and classrooms. Public school is free, but families still cannot afford to send their children for a complicated network of reasons. In this editorial for the Pinoy Press, one author delineates the key issue:

With around 65 million Filipinos or about 80 percent of the population trying to survive on P96 ($2) or less per day, how can a family afford the school uniforms, the transportation to and from school, the expenses for school supplies and projects, the miscellaneous expenses, and the food for the studying sibling? More than this, with the worsening unemployment problem and poverty situation, each member of the family is being expected to contribute to the family income. Most, if not all, out-of-school children are on the streets begging, selling cigarettes, candies, garlands, and assorted foodstuffs or things, or doing odd jobs.

Beyond the selling goods on the street, children in farming families are expected to work in the fields during harvest time. In agriculture-based communities where farming is the primary livelihood, having children around to help with the work means more income for the family. In a recent trip to Valladolid, someone told me that children are paid 15 pesos for a day’s work in the blistering heat. They are pulled from school for two or three months at a time and are irreparably disadvantaged compared with their classmates. So, they may have to repeat the grade, only to be pulled out of school again next year.

Beyond the selling goods on the street, children in farming families are expected to work in the fields during harvest time. In agriculture-based communities where farming is the primary livelihood, having children around to help with the work means more income for the family. In a recent trip to Valladolid, someone told me that children are paid 15 pesos for a day’s work in the blistering heat. They are pulled from school for two or three months at a time and are irreparably disadvantaged compared with their classmates. So, they may have to repeat the grade, only to be pulled out of school again next year.

Transportation is another big problem. Kids walk 2-3 kilometers or more to and from school every day. They have to cross rivers and climb hills with their bookbags. The ones that can afford it take a tricycle, but that is a luxury. Schools are sometimes too far for the most remote communities to practically access. So the families can’t afford to pay and the children are pulled from school.

It seems like an intractable problem. Corruption in the education bureaucracy and a lack of resources make delivering a high-quality education to all Filipinos a challenge. Microfinance is one way to help. With the assistance of microcredit loans, women can pay for the education of their children – to purchase uniforms, textbooks, lunches, and rides to school. Also, by creating another source of income other than farming, the children do not have to come help the family work the fields. When I talk to NWTF clients about their dreams, they unfailingly say they hope for their children to “finish their studies.” History has shown that it is an achievable goal. But real systemic change needs to come from above. As long as corruption and bureaucracy paralyzes the system, the goal of delivering a decent education to children – which pays dividends to the country in the long run – will remain out of reach.

For the rural poor, non-profits exist to help in the mission of education. While looking up pictures for this post, I came across a Filipino organization called the Gamot Cogon (“Grass Roots”) Institute:

The Gamot Cogon Institute (a non-stock, non-profit organization) is an Iloilo-based cultural institution working to transform society through human development approaches including education and training. GCI also prototypes or demonstrates alternative approaches to education, agriculture, health, and full human development.

Very cool stuff.

Develop Economies’ Music Recommendation

The other day, I talked about the first of the four reasons why we cannot end poverty in the United States. Now I will talk about the other three.

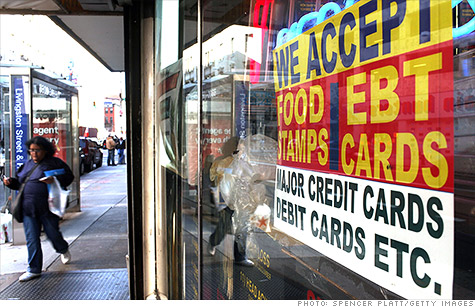

The other day, I talked about the first of the four reasons why we cannot end poverty in the United States. Now I will talk about the other three. The chart on the right shows spending on low-income programs, with and without Medicare and Social Security, as a percentage of real GDP over time. In the War on Poverty during the LBJ administration, federal spending increased significantly before leveling off until the recession in 2008. It has increased since Obama took office, primarily in response to the downturn, which increased the rolls of people in need. Despite this mini-surge in spending, there a danger that it could be reversed.

The chart on the right shows spending on low-income programs, with and without Medicare and Social Security, as a percentage of real GDP over time. In the War on Poverty during the LBJ administration, federal spending increased significantly before leveling off until the recession in 2008. It has increased since Obama took office, primarily in response to the downturn, which increased the rolls of people in need. Despite this mini-surge in spending, there a danger that it could be reversed.