There are four reasons, says Peter Edelman, author of “So Rich, So Poor: Why It’s So Hard to End Poverty in America”:

With all of that, why have we not achieved more? Four reasons: An astonishing number of people work at low-wage jobs. Plus, many more households are headed now by a single parent, making it difficult for them to earn a living income from the jobs that are typically available. The near disappearance of cash assistance for low-income mothers and children — i.e., welfare — in much of the country plays a contributing role, too. And persistent issues of race and gender mean higher poverty among minorities and families headed by single mothers.

In the wake of the recession, with so many people currently unemployed, the poverty level in the U.S. continues to grow. And, while Edelman’s diagnosis is right, the fixes for at least some of the problems seem more difficult. The number of low-wage jobs in America reflects the spread of globalization and the movement of jobs overseas. This process has been ongoing for several decades, as manufacturing steadily moved abroad and, increasingly service industries, like call centers and business process outsourcing, followed suit. Ironically, America’s loss became the developing world’s gain, as hundreds of millions of people climbed above the poverty line in places like China, India, Brazil, and the Philippines. On a global scale, the trend toward low-wage jobs in the United States may actually reflect a global poverty reduction trend.

In the wake of the recession, with so many people currently unemployed, the poverty level in the U.S. continues to grow. And, while Edelman’s diagnosis is right, the fixes for at least some of the problems seem more difficult. The number of low-wage jobs in America reflects the spread of globalization and the movement of jobs overseas. This process has been ongoing for several decades, as manufacturing steadily moved abroad and, increasingly service industries, like call centers and business process outsourcing, followed suit. Ironically, America’s loss became the developing world’s gain, as hundreds of millions of people climbed above the poverty line in places like China, India, Brazil, and the Philippines. On a global scale, the trend toward low-wage jobs in the United States may actually reflect a global poverty reduction trend.

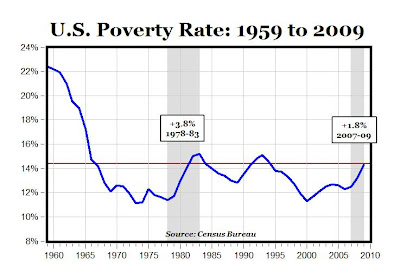

Still, working a low-wage job in the U.S. is no doubt difficult. More than 100 million people – nearly a third of the population – live below twice the poverty line ($38,000 for a family of three). Edelman says that this trend has been ongoing since the 80’s, but we only opened our eyes after the recession. This is true, but doesn’t tell the whole story. Amidst one of the longest, deepest recessions since the Great Depression, corporate profits have broken records for the last three years. As companies retrenched and laid off their employees to cope with a crash in demand, they became more nimble and cost-conscious. As the economy recovered, instead of hiring back old employees, they outsourced jobs overseas or automated wherever possible, lowering their operating costs and increasing profits. In the long-run, the U.S. economy will be stronger and more globally-competitive as a result. But, in the short-term, the number of people living below the poverty line in the US will surely increase.

Those jobs are not coming back. Edelman suggests investing more heavily in education and skill development, and I agree. Because the funding source is local, our current public education system is failing to educate huge swathes of the population in a vicious cycle that creates a poverty trap. Setting aside the fact that discriminating on the basis of zip code is morally wrong, as I have discussed on this blog, it will only exacerbate our competitiveness problem.

Those jobs are not coming back. Edelman suggests investing more heavily in education and skill development, and I agree. Because the funding source is local, our current public education system is failing to educate huge swathes of the population in a vicious cycle that creates a poverty trap. Setting aside the fact that discriminating on the basis of zip code is morally wrong, as I have discussed on this blog, it will only exacerbate our competitiveness problem.

On the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) test, a global test given to 470,000 students in 2010, the U.S. ranked 14th in reading, 17th in science, and 25th in math. But these numbers do not tell the entire story. When the results are segmented by the percentage of students participating in the subsidized lunch program, which is the most accurate gauge of poverty levels in schools, the level of stratification is striking. In schools where less than 10% of students apply for subsidized lunch, the U.S. has the highest PISA scores of any OECD nation. In schools with more than 50% participation, the U.S. sits between Austria and Luxembourg. Mel Riddle, the head of the National Association of Secondary School Principals, explains the other side of that coin:

The problem is not as much with our educational system as it is with our high poverty rates. The real crisis is the level of poverty in too many of our schools and the relationship between poverty and student achievement. Our lowest achieving schools are the most under-resourced schools with the highest number of disadvantaged students. We cannot treat these schools in the same way that we would schools in more advantaged neighborhoods or we will continue to get the same results. The PISA results point out that the U.S. is not alone in facing the challenge of raising the performance of disadvantaged students.

This is a travesty for a number of reasons. Not only are we denying huge numbers of children a decent education, we are also diminishing our own competitiveness as a nation in the future.

In the next post, I will talk about the other three reasons.

Develop Economies’ Music Recommendation

Pingback: The Intangible Wealth of Nations | Develop Economies