Over the past few weeks, social impact bonds have received a lot of attention. That is because New York City has partnered with Goldman Sachs to run a pilot program aimed at reducing recidivism among inmates at Rikers Island prison. But first, a little background on social impact bonds.

There are many social problems for which there is no clear-cut solution. Homelessness, foster care, inmate recidivism, and other issues are often expensive to control. Programs designed to address them are often part of large bureaucracies and susceptible to the same inefficiencies and perverse incentives endemic in other government agencies. And, despite best efforts to fix the problems, they will only get worse as social programs move closer to the chopping block.

Non-profits supplement government efforts by addressing specific problems. Halfway houses, community health clinics, shelters, low-income housing developments, and soup kitchens are all examples of non-governmental organizations serving the homeless. Many have developed innovative approaches that are effective in achieving specific goals – i.e. placing homeless in low-income housing, job-training, etc. – but are constrained by a lack of capital. Without access to greater resources, non-profits will never be able achieve scale.

So the government has lots of money, but not enough dynamic programs to fund. In contrast, non-profits run effective programs on a small scale, but lack the money to expand. This is where social impact bonds come in.

In a social impact bond, the government contracts an intermediary to put together a social impact bond to address a specific social problem. The intermediary then identifies non-profits with promising potential and connects them with investors. The investors provide multi-year funding to the non-profit, allowing them to scale their intervention. In return, the investor is reimbursed by the government based to the program’s success. A monitoring-and-evaluation firm is brought in to assess the impact, which is based on a pre-determined set of metrics. If the intervention achieves the targets, the investor makes a return on the bond. If not, it takes a loss.

The best way to explain the mechanics of a social impact bond is to provide a real-world example. In the case of New York City and Goldman Sachs, the city government wants to reduce the number of repeat offenders, which cost taxpayers money in the form of prison costs, increased law enforcement, and lost productivity. Here is how it works:

The Goldman money will be used to pay MDRC, a social services provider, to design and oversee the program. If the program reduces recidivism by 10 percent, Goldman would be repaid the full $9.6 million; if recidivism drops more, Goldman could make as much as $2.1 million in profit; if recidivism does not drop by at least 10 percent, Goldman would lose as much as $2.4 million.

It seems like a win-win situation, if investors see social impact bonds as a viable means of earning a financial return. I am mostly in favor of any programs that place greater emphasis on “outcomes over outputs.” But this emphasis is hardly new in the international development community, which has seen a surge in rigorous testing for interventions after economists like Dean Karlan, Esther Duflo, and Abhijit Banerjee popularized the use of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to determine the efficacy of different approaches. And I have the same concerns about social impact bonds that I do about RCTs.

Tying financial returns to outcomes creates two potential problems. First, it risks incentivizing the wrong things, a la “teaching to the test.” Often, these problems are extraordinarily complex and difficult to address, and rarely lend themselves to a timeline that works with an investment. In microfinance, for example, most RCTs occur over 2-3 years, and have shown little improvement in the well-being of recipients. I would argue it takes much longer than 2-3 years to realize the fruits of microfinance. If that is the case, which timeline will be used for the social impact bond – the one that shows progress, or the one that doesn’t?

For some issues, this is not a concern. Recidivism, for example, is cut-and-dry. Chronic homelessness, however, is not. For social impact bonds to be successful, they will require metrics that truly reflect the success of the program.

The second problem is that the interconnectedness of institutions can mask success. Mark Rosenman of Caring to Change explains both of these problems (h/t Democracy in America):

Where does a nonprofit get the funding to provide the services from which they are to later show a monetized gain to government? How far out in time does the performance metric need to go before quantifiable economic value can be shown and the charity repaid its expenditures? What happens when a nonprofit is providing superb and highly effective services to individuals, but other institutions and variables deteriorate and affect its outcomes?

These are very real concerns that the international development community has been forced to confront (or avoid) in its work.

I am not as pessimistic as Mr. Rosenman or Mr. Steinglass. I think that social impact bonds are a pragmatic and innovative solution to a very real problem. In addition to capital, investors will bring human resources and technology to bear on the problem, which will infuse the sector with new ideas and perspectives. Social impact bonds are still in their nascent stages, but, if they can figure out a way to effectively capture success rates and avoid the pitfalls of “juking the stats,” I see no reason why they can’t be a game-changer in the fight to address social problems.

Develop Economies’ Music Recommendation

The

The

A friend posted an article on his Facebook wall titled “

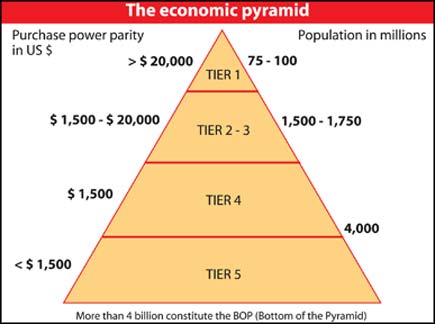

A friend posted an article on his Facebook wall titled “ There is a myth of a fortune at the bottom of the pyramid, according to Toyama. At least, that fortune is purely measured in market size and raw purchasing power. It should not be confused with an opportunity to offer products that alleviate poverty and make a bundle to boot. The rural and even urban poor are difficult markets to serve profitably. A disparate and sometimes non-existent supply chain makes getting products in the hands of consumers a challenge even for the biggest multinationals. Branding products for the poor, or subsidizing them, makes them less appealing to the middle class, who might pay more and create cross-subsidization opportunities (on this point, I think he is wrong, having seen the same solar lanterns we were selling to microfinance clients in the Philippines being sold in malls in Manila for twice the price). Not to mention, selling products to the poor is not going to help them out of poverty. Employment, in the form of manufacturing and labor-intensive work, is the key to growth. In short, it is possible to serve a social cause, and it is possible to make lots of money selling products to the poor. But to do both simultaneously? Very difficult.

There is a myth of a fortune at the bottom of the pyramid, according to Toyama. At least, that fortune is purely measured in market size and raw purchasing power. It should not be confused with an opportunity to offer products that alleviate poverty and make a bundle to boot. The rural and even urban poor are difficult markets to serve profitably. A disparate and sometimes non-existent supply chain makes getting products in the hands of consumers a challenge even for the biggest multinationals. Branding products for the poor, or subsidizing them, makes them less appealing to the middle class, who might pay more and create cross-subsidization opportunities (on this point, I think he is wrong, having seen the same solar lanterns we were selling to microfinance clients in the Philippines being sold in malls in Manila for twice the price). Not to mention, selling products to the poor is not going to help them out of poverty. Employment, in the form of manufacturing and labor-intensive work, is the key to growth. In short, it is possible to serve a social cause, and it is possible to make lots of money selling products to the poor. But to do both simultaneously? Very difficult.

A little more than one year ago, I was working with Negros Women for Tomorrow Foundation, a microfinance in the Philippines. NWTF was distributing low-cost solar lanterns to its clients. The clients were prone to constant brownouts due to the poor state of the electrical infrastructure in the rural areas, so the lanterns gave them a way to keep their businesses open after dark or let the children do work after the sun goes down. Having limited access to light, or having to rely on costly alternatives (battery-powered lanterns and kerosene) can really rain on a person’s parade. So, in conjunction with Kiva, we worked to get those loans for the solar lanterns up on the site. On Earth Day 2010, the relationship was consummated and celebrated with a blog post by yours truly on the Kiva blog, which you can

A little more than one year ago, I was working with Negros Women for Tomorrow Foundation, a microfinance in the Philippines. NWTF was distributing low-cost solar lanterns to its clients. The clients were prone to constant brownouts due to the poor state of the electrical infrastructure in the rural areas, so the lanterns gave them a way to keep their businesses open after dark or let the children do work after the sun goes down. Having limited access to light, or having to rely on costly alternatives (battery-powered lanterns and kerosene) can really rain on a person’s parade. So, in conjunction with Kiva, we worked to get those loans for the solar lanterns up on the site. On Earth Day 2010, the relationship was consummated and celebrated with a blog post by yours truly on the Kiva blog, which you can

The other day a friend put me in touch with a friend of his who had just moved to Accra. She works the

The other day a friend put me in touch with a friend of his who had just moved to Accra. She works the