“[Africa] is a wonderful place to really make money. We have one billion people hungry for everything.” Mo Ibrahim

A friend posted an article on his Facebook wall titled “Why Social Impact Investing is a Crock,” leaving much to the imagination. Here is an excerpt:

A friend posted an article on his Facebook wall titled “Why Social Impact Investing is a Crock,” leaving much to the imagination. Here is an excerpt:

Over the last decade the world of do-gooding has seemingly been taken over by MBAs. Social entrepreneurship, a field encompassing both mission-driven businesses and entrepreneurial nonprofits, professes to bring the efficiency, rigor, and cold, hard metrics of business to the most important causes on the planet. Does it really? Not so much, says Dean Karlan, author of the recent book More Than Good Intentions. “The social entrepreneurship world is in a weird spot, to be honest with you. It’s a world full of rhetoric about impact investing, yet I have very rarely seen an investor actually take that seriously. When you look at the actual analysis it lacks rigor.” He distinguishes between the type of scientific research done by his lab, Innovations for Poverty Action, with trials complete with control groups, and the type of data collection done in the vast majority of the nonprofit world, which is nothing more than a “monitoring exercise.”

I think both Karlan and the author have the right idea, but for the wrong reasons. Later in the article, Karlan explains why the cost of doing a rigorous impact analysis is cost prohibitive for an investor who is focused on financial returns, with impact studies accounting for as much as a third of the investment. I think the title of the article is excessive and meant to be provocative, but the argument is defensible.

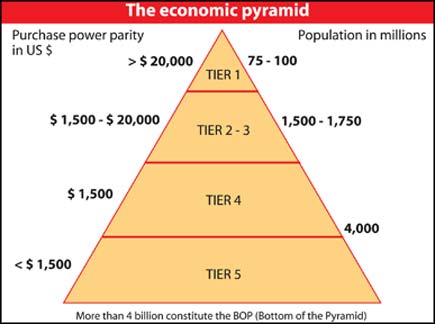

The other day I listened to a presentation from Kentaro Toyama, one of the eminent thinkers in ICT (information, communication, and technology) for development (ICT4D, for short), a school of thought that sees technology as the silver bullet in ending poverty. His talk was titled “ICT or Development: Why it’s so hard to get rich and help the poor simultaneously.” It was also meant to be provocative, but for a different reason. Toyama’s point is not that the absence of verifiable impact makes impact investing a crock. Rather, he contends that it is difficult, if not impossible, to get rich by providing socially-beneficial goods and services to the base of the economic pyramid. You can get rich selling products to the poor, but they won’t necessarily be good (alcohol, tobacco, soda, etc.). Conversely, you can sell products that will address a social need (solar lanterns, cookstoves, etc.), but you won’t get rich doing it. He challenged the audience to come up with an example, and explained why his thesis holds in each case.

There is a myth of a fortune at the bottom of the pyramid, according to Toyama. At least, that fortune is purely measured in market size and raw purchasing power. It should not be confused with an opportunity to offer products that alleviate poverty and make a bundle to boot. The rural and even urban poor are difficult markets to serve profitably. A disparate and sometimes non-existent supply chain makes getting products in the hands of consumers a challenge even for the biggest multinationals. Branding products for the poor, or subsidizing them, makes them less appealing to the middle class, who might pay more and create cross-subsidization opportunities (on this point, I think he is wrong, having seen the same solar lanterns we were selling to microfinance clients in the Philippines being sold in malls in Manila for twice the price). Not to mention, selling products to the poor is not going to help them out of poverty. Employment, in the form of manufacturing and labor-intensive work, is the key to growth. In short, it is possible to serve a social cause, and it is possible to make lots of money selling products to the poor. But to do both simultaneously? Very difficult.

There is a myth of a fortune at the bottom of the pyramid, according to Toyama. At least, that fortune is purely measured in market size and raw purchasing power. It should not be confused with an opportunity to offer products that alleviate poverty and make a bundle to boot. The rural and even urban poor are difficult markets to serve profitably. A disparate and sometimes non-existent supply chain makes getting products in the hands of consumers a challenge even for the biggest multinationals. Branding products for the poor, or subsidizing them, makes them less appealing to the middle class, who might pay more and create cross-subsidization opportunities (on this point, I think he is wrong, having seen the same solar lanterns we were selling to microfinance clients in the Philippines being sold in malls in Manila for twice the price). Not to mention, selling products to the poor is not going to help them out of poverty. Employment, in the form of manufacturing and labor-intensive work, is the key to growth. In short, it is possible to serve a social cause, and it is possible to make lots of money selling products to the poor. But to do both simultaneously? Very difficult.

My friends and I discussed the talk over lunch. Most felt that the talk was good, but thought Toyama oversimplified a complex topic, creating a dichotomy that practitioners don’t really subscribe to. Anyone who honestly thinks that you can make serious money – young-rich Silicon Valley money – by selling socially-conscious products and services to the poorest segments of the world population is clearly dreaming. So that conversation should be a non-starter. You can make money, sure, and you do a lot of good, but if you’re goal is to get rich, then you are in the wrong business. For that reason, we all concluded that the talk wasn’t meant for people like us. It was meant for the people in Silicon Valley who have become a little too excited envisioning that Venn diagram.

During the talk, I asked Toyama what he thought of social impact investing. Basically, he thought it went through a period of irrational exuberance, where people thought they could make high returns and serve a social good, before dipping once people realized that was not the case. It has made a slight resurgence, as people have checked their expectations and come to sacrifice financial returns for social impact. What Dean Karlan and Kentaro Toyama have in common is that they both believe that it is very difficult to both make good money and help the poor. Karlan thinks the social impact of many investments is unproven, while Toyama thinks the social impacts are fine, but making money is a challenge.

The legacy of Mo Ibrahim

I happen to disagree with both. Ten years ago, a telecom industry in Africa barely existed. Today, most of the population, regardless of whether they are living in poverty, owns a cell phone. When I brought up this point, Toyama says that the telecoms are entirely profit-oriented, and could care less about helping the poor. Someone earning a dollar a day, for example, will think nothing of spending a quarter on a ringtone. But to say that the development of a mobile network that connects the most remote parts of Africa to the rest of the world has not helped the poor by several orders of magnitude is crazy. It is ironic to me that people interested in this developing products for the poor always leverage the cell phone revolution in Africa, but never seem to give it any credit for laying the groundwork for real, substantive change and improvement – moving the needle over generations, rather the 2-3 year time periods for the randomized control trials being used to measure impact. (My intention here isn’t to write off RCTs – rather to say that maybe there is a broader way of looking at impact).

There is often a paternalistic attitude (not necessarily among people like Toyama or Karlan, but others less in the know) toward serving the poor. People try to engineer outcomes, and are dismayed when someone spends the extra income from the dairy cow they bought with help from a microfinance loan on booze, cigarettes, and fast women. Judge not, I say, lest ye be judged. After all, in the words of Devin the Dude, “you only get one ticket, might as well enjoy the ride.”

Creating more opportunities should be the barometer of success in serving the poor. Microfinance was about providing access to financial services, which it did. It has given poor people a place to save their money and borrow money to smooth their irregular consumption. It created opportunities that did not exist. In a much less outwardly altruistic example, connecting Africa to the world and putting a cheap cell phone in the hands of every African is helping the poor and making a killing. If the poor then spend the school fees on ringtones, that is their discretion. But creating opportunity – in the form of infrastructure or technology – is what moves the needle.

That is why, in my opinion, social impact investors need to move in one of two different directions. They can either expand the definition of social impact beyond the “directly reach a million poor people” definition that exists today, and accept the fact that there is highly profitable companies that serve a social cause and are specifically targeted at the poor are few and far between. Or, they can accept the fact that the returns will be marginal, but the intangible social value created by the product will significantly exceed the financial opportunity cost. Either way, the current narrative that you can make lots of money and serve the poor at the same time (rather than serially, like Bill Gates, as Toyama suggests) is dangerous.

But where's the impact?

It is dangerous because it breeds unrealistic expectations and creates resentment when they fall short (“Impact investing is a crock! Those assholes lied to us!”). Social entrepreneurs shouldn’t feel like they have to be 100% financial sustainable to be successful. That is a nice-to-have, but there are billions of dollars being spent very poorly on development projects right now. Money is not an issue (Kiva, for example gets money with 0% returns) – impact is the problem. Similarly, investors shouldn’t measure success by the direct impact on the lives a certain number of poor people, or hitting specific targets in living standard improvement. They should invest in Africa, but do it responsibly. Stay away from oil, cigarettes, alcohol, or any other product that has a net-negative social impact, and focus on telecommunications, manufacturing, or even natural resources (so long as workers are treating well). Investment will generate employment, which, as Toyama says, is the real engine of poverty alleviation.

Until people recalibrate what it means to a) make money, and b) have an impact, and convey these goals honestly, I’m afraid social impact investing will continue to fall short of the expectations and face the same circular firing squad that has plagued other “silver bullets”, like microfinance. I think real social entrepreneurs and impact investors understand this push-and-pull. But Toyama’s intended audience is probably less informed about the realities on the ground, which is why he was giving the talk in the first place.

There are fewer examples of companies and organizations targeting the underlying the issues that lead to systemic change, but the ones that have been successful have changed the world. Mo Ibrahim is a Sudanese-British mobile communications entrepreneur. He founded the company Celtel, a telecommunications company that

There are fewer examples of companies and organizations targeting the underlying the issues that lead to systemic change, but the ones that have been successful have changed the world. Mo Ibrahim is a Sudanese-British mobile communications entrepreneur. He founded the company Celtel, a telecommunications company that  Another game-changing technology is mobile money. In 2007,

Another game-changing technology is mobile money. In 2007,

Develop Economies is back after a brief hiatus. I have finished up my work on my current project and am now taking some time to appreciate some of the aspects of Ghana I hadn’t had a chance to enjoy previously. I spent a few days living with a rice farmer about 45 minutes by motorbike from Atsusuare in a small community along a lake fed by the Volta River. I did some work in the field (very minor – I can’t say I’m a great farmer), came across two cobra snakes, and biked an hour each way to the next village with electricity to charge my cell phone and camera. It was the first time I have ever actually experienced rural living, with no electricity, no running water, limited transportation (you have to call a motorbike to pick you from the neighboring town), and the persistent threat of snakebites, malaria, and other calamities that hang around waterlogged fields of paddy rice. I have discussed on this blog the different solutions to the problems of rural energy delivery and distributed power generation, to the problem of inefficiency of burning charcoal and the use of clean-burning cookstoves, and others. But I had never actually seen any of it or experienced it with my own eyes.

Develop Economies is back after a brief hiatus. I have finished up my work on my current project and am now taking some time to appreciate some of the aspects of Ghana I hadn’t had a chance to enjoy previously. I spent a few days living with a rice farmer about 45 minutes by motorbike from Atsusuare in a small community along a lake fed by the Volta River. I did some work in the field (very minor – I can’t say I’m a great farmer), came across two cobra snakes, and biked an hour each way to the next village with electricity to charge my cell phone and camera. It was the first time I have ever actually experienced rural living, with no electricity, no running water, limited transportation (you have to call a motorbike to pick you from the neighboring town), and the persistent threat of snakebites, malaria, and other calamities that hang around waterlogged fields of paddy rice. I have discussed on this blog the different solutions to the problems of rural energy delivery and distributed power generation, to the problem of inefficiency of burning charcoal and the use of clean-burning cookstoves, and others. But I had never actually seen any of it or experienced it with my own eyes. A little more than one year ago, I was working with Negros Women for Tomorrow Foundation, a microfinance in the Philippines. NWTF was distributing low-cost solar lanterns to its clients. The clients were prone to constant brownouts due to the poor state of the electrical infrastructure in the rural areas, so the lanterns gave them a way to keep their businesses open after dark or let the children do work after the sun goes down. Having limited access to light, or having to rely on costly alternatives (battery-powered lanterns and kerosene) can really rain on a person’s parade. So, in conjunction with Kiva, we worked to get those loans for the solar lanterns up on the site. On Earth Day 2010, the relationship was consummated and celebrated with a blog post by yours truly on the Kiva blog, which you can

A little more than one year ago, I was working with Negros Women for Tomorrow Foundation, a microfinance in the Philippines. NWTF was distributing low-cost solar lanterns to its clients. The clients were prone to constant brownouts due to the poor state of the electrical infrastructure in the rural areas, so the lanterns gave them a way to keep their businesses open after dark or let the children do work after the sun goes down. Having limited access to light, or having to rely on costly alternatives (battery-powered lanterns and kerosene) can really rain on a person’s parade. So, in conjunction with Kiva, we worked to get those loans for the solar lanterns up on the site. On Earth Day 2010, the relationship was consummated and celebrated with a blog post by yours truly on the Kiva blog, which you can

For my

For my  A month later I was accepted to the Kiva Fellows program and given my assignment in the Philippines. As it turned out, I was placed with NWTF, the very same MFI that Arc Finance was doing a pilot with. So, when I got down to Bacolod, I worked together with Kiva, Arc Finance, and NWTF to get the loans up on the website. We were the first MFI in

A month later I was accepted to the Kiva Fellows program and given my assignment in the Philippines. As it turned out, I was placed with NWTF, the very same MFI that Arc Finance was doing a pilot with. So, when I got down to Bacolod, I worked together with Kiva, Arc Finance, and NWTF to get the loans up on the website. We were the first MFI in