I. Introduction

In August of 2014, a police officer shot dead Michael Brown, a black teenager from Ferguson, Missouri, blowing the lid off a debate about racism in America. Protesters filled the streets, yelling “Hands up, don’t shoot.” The hashtag “#blacklivesmatter” began trending on Twitter. A few weeks before, bystanders filmed a police officer in Staten Island choking to death Eric Garner, an African-American man who’d been arrested for selling untaxed cigarettes. When the grand jury chose not to bring charges against the officers responsible for the deaths of Brown and Garner, many Americans sadly shook their heads.

This isn’t the first time the deaths of young black men have sparked a national conversation about race. In 2012, George Zimmerman shot and killed Trayvon Martin, an unarmed black teenager in Florida. On New Years Day in 2009, a police officer shot Oscar Grant, a 23 year-old black man, point blank while on top of him at Fruitvale Station in Oakland, California (a film was later made about his death). But unlike in those incidents, the conversation stemming from Ferguson has continued long past the shooting, in part due to a string of stories of overt racism around the country. In March of 2015, a video surfaced showing members of SAE, a fraternity at the University of Oklahoma, singing a racist song on a bus. The fraternity chapter was disbanded, the students expelled, and the national conversation about race and privilege continued.

These incidents are not unique, but are considered emblematic of a broader societal problem with racism in America. Police unfairly target people of color, filling prisons with blacks and hispanics and criminalizing generations of young people. In Ferguson and the communities around St. Louis, municipalities effectively run debtors prisons, jailing people for minor infractions like an expired tag or broken tail light. In 2013, Ferguson alone issued 32,975 arrest warrants for its 21,135 people, overwhelmingly to African-Americans. Clearly, there is a problem.

Unfortunately, these incidents, and even the unjust policies they exposed, are symptoms of the much larger, more nefarious disease of institutional racism. Unlike the overt racism on display in the shooting of Michael Brown or the chants of drunk fraternity members in Oklahoma, institutional racism is not easily seen, measured, or even defined. It has no beginning or end, having permeated every aspect of our society, and its effects are felt all around us. Michael Brown’s death, like Trayvon Martin’s death and Eric Garner’s death, was the output of a system so deeply corrupted by institutional racism that outcomes like these are not only unsurprising, but expected.

In this essay, I will explain the concept of institutional racism, (try to) break down the components of the complex systems that govern society, and explain how institutional racism within those component parts creates a self-reinforcing, unjust system where ethnic minorities are discriminated against not only by individuals within the system, but by the system itself.

II. Unpacking Institutional Racism

It makes sense to start with a definition of institutional racism. From Wikipedia:

Institutional racism is the differential access to the goods, services, and opportunities of society. When the differential access becomes integral to institutions, it becomes common practice, making it difficult to rectify. Eventually, this racism dominates public bodies, private corporations, and public and private universities, and is reinforced by the actions of conformists and newcomers. Another difficulty in reducing institutionalized racism is that there is no sole, true identifiable perpetrator. When racism is built into the institution, it appears as the collective action of the population.

Institutional racism is a difficult concept to unpack because discrimination is rarely overt or entirely unjustified. It can be subtle and almost imperceptible at the individual level, and often stems from discrimination within another system. Let’s look at particular example and trace it back to the origins.

Institution 1: The Prison

Anthony is a 22 year-old African-American kid living in the Queensbridge Housing Projects in Queens, New York. He’s got a girlfriend and a two year-old baby boy, and has been selling drugs since he was a teenager. When he is arrested for selling a small amount of crack cocaine, he is sent to jail on $1,000 bail, which neither he nor his family can afford to pay, so he ends up staying in jail until his trial. Because he has a prior record, the odds are not in his favor when he finally gets his day in court.

In 2009, the incarceration rate of black males in the U.S. was six times that of whites. Is that because blacks are more likely to go to prison than white people? Perhaps. According a report from the Sentencing Project, white Americans overestimate the proportion of crime committed by people of color and tend to support more punitive measures even though they experience less crime. In Florida, a Washington Post poll found that whites believed 50% of crimes were committed by black people, when the real number is closer to 20%. This bias makes them more likely to support tough-on-crime policies, which politicians are more than willing to oblige.

As a result, blacks are both more likely to be convicted of crimes and receive longer sentences than whites. Nationwide, blacks are 10 times more likely to go to jail for drug offenses. In 2012, a study found that blacks and Hispanics received longer sentences for the same or lesser offenses than white offenders. People of color remain in prison longer and naturally comprise a larger percentage of the prison population.

As a result, blacks are both more likely to be convicted of crimes and receive longer sentences than whites. Nationwide, blacks are 10 times more likely to go to jail for drug offenses. In 2012, a study found that blacks and Hispanics received longer sentences for the same or lesser offenses than white offenders. People of color remain in prison longer and naturally comprise a larger percentage of the prison population.

If he could afford a lawyer, Anthony might receive a lighter sentence. But he can’t, so he is assigned an overworked public defender who might be meeting him for the first time on the day of his trial, and he appears before a judge wearing a jail uniform, since he couldn’t afford bail. Meanwhile, he’s been evicted from his apartment because he has been in jail, and his girlfriend and baby are staying at her mother’s house, while the primary breadwinner is sitting in jail, unable to work. With a few strikes against him, he receives two years and is sent to prison.

Anthony isn’t the only one dealing drugs in New York City, but this isn’t the first time he’s been arrested. The next questions is: why are so many blacks arrested in the first place?

Institution 2: The Police

Anthony hangs out on the corners and is frequently stopped by the police and searched. Because Queensbridge has a history of drug-dealing, there is a strong police presence in this overwhelmingly black and Latino neighborhood. People in the community have an uneasy relationship with the police, who simultaneously make the neighborhood safer and arrest young people in much higher numbers than in the rest of the city.

Part of the problem is that black males are unfairly targeted by police officers. In New York, a controversial policy called “stop-and-frisk” allows police to stop and question a pedestrian before searching them for guns and contraband. Despite the fact that blacks and Latinos make up 52.6% of the population, they consistently account for 85% of stop-and-frisk encounters. And, if they’re caught, blacks are four times more likely to be arrested for marijuana possession and selling, despite consuming the drug at largely same proportion as white people.

Stop-and-frisk has a notoriously low yield, subjecting thousands of innocent people to unnecessary searches.

So it is true the police are overwhelmingly targeting people like Anthony, who was arrested in a stop-and-frisk encounter. And the stats seem to support a pattern of profiling. New York City releases a report on race and crime statistics every year. In 2012, blacks and Hispanics accounted for 73% of arrestees for misdemeanor mischief, compared with 23% for whites. It is certainly possible, and even probable, that whites are getting away with more crimes than people of color. But blacks and Hispanics are, at the very least, getting caught more often.

The police argue that they’re job is to stop crimes, and arrest those who are committing them, whether they are black, white, or any other color. When asked about racial bias in Ferguson, former NYC mayor Rudy Giuliani asked: “I find it very disappointing that you’re not discussing the fact that 93 percent of blacks in America are killed by other blacks.” In a similar vein, responding to critics of stop-and-frisk, the NYPD released a report in mid-2012 showing that people of color made up 96% of shooting victims and 97% of shooting suspects during the first half of the year. The police commissioner, Raymond Kelly, defended stop-and-frisk as “proactive engagement”, calling it a “life-saving measure.” In other words, we’d arrest fewer black people if they committed fewer crimes.

Of course, these shooting suspects represent a tiny fraction of black and Latino youth in NYC, and hardly justify such a blunt policy. Still, given these realities, it is possible to see why police officers would target Anthony for reasons other than racial bias.

Institution 3: The City

Regardless of policy, Anthony was stopped because the police felt they had reason to suspect he may be engaged in illegal activity, so they approached him. But part of the problem is that Anthony lives in Queensbridge, a housing project with a pattern of gang violence and drug dealing. And that means cops approach kids in Queensbridge like Anthony all the time.

The concentration of violent crime around certain geographies has given rise to programs like predictive policing, which uses data analytics to identify crime hotspots and preemptively deploy resources to prevent crimes before they occur. Because those crimes are often committed in predominantly ethnic neighborhoods, police presence is higher and more people of color are arrested. The resulting higher arrest rates are not necessarily due to overt racial bias, but actually an analysis of where crimes are most likely to occur. And, in Anthony’s case, Queensbridge fits the bill.

In the ten highest crime precincts, there are 16.9 stops per 100 residents – three times the city average (Source: NYT)

So why do specific urban neighborhoods like Queensbridge have such a problem with crime? Sociologists, criminologists, and economists have tried to answer that question for decades, and proposed several explanations. Conflict theory is one of the more prominent criminological explanations for the concentration of crime in certain neighborhoods:

As a general theory of criminal behavior, conflict theory proposes that crime is an inevitable consequence of the conflict which arises between competing groups within society. Such groups can be defined through a number of factors, including class, economic status, religion, language, ethnicity, race or any combination thereof. Sociologists and criminologists emphasizing this aspect of social conflict argue that, in a competitive society in which there is an inequality in the distribution of goods, those groups with limited or restricted access to goods will be more likely to turn to crime.

According to conflict criminology theory, people with fewer means are more likely to turn to crime to make ends meet. And, in a self-fulfilling way, crime begets crime – a fact that underlies the controversial broken windows theory of policing.

It is critical to note that poverty, not race, explains high levels of crime in this and just about every other theory of criminology. The link between poverty and crime is well-documented, going all the way back to Aristotle, who said, “Poverty is the parent of revolution and crime.” In a 2005 paper in the American Journal of Public Health titled “Social Anatomy of Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Violence”, three researchers from the Rand Corporation posit that the relationship between race and crime is based on underlying factors specific to racial groups:

Our theoretical framework does not view “race” or “ethnicity” as holding distinct scientific credibility as causes of violence. Rather, we argue they are markers for a constellation of external and malleable social contexts that are differentially allocated by racial and ethnic status in American society. We hypothesize that segregation by these social contexts in turn differentially exposes members of racial and ethnic minority groups to key violence-inducing or violence-protecting conditions.

The authors go on to offer a few statistically-significant examples of those social contexts, including marital status of parents, immigrant generation, and neighborhood characteristics associated with racial segregation. So, what exactly is it about these neighborhoods that help to explain the propensity to commit crimes?

Institution 4: The Neighborhood

Anthony’s neighborhood, Queensbridge, is the largest housing project in the borough of Queens in New York City. It was first built in 1939, and has around 6,500 residents at any given time. During the late 1950’s, the management converted it to a low-income housing project, transferring families with an annual income of more than $3,000/year, most of whom were white, to a middle-income project, leaving a predominantly poor black and Hispanic population.

Throughout the 70’s and 80’s, poverty increased, and Queensbridge became notorious for the prevalence of crime, gaining the dubious distinction of having the most murders of any project in New York in 1986. Queensbridge’s most famous resident, Nas, described growing up there in the song, “Memory Lane”, from one of your correspondent’s favorite albums, Illmatic:

My window faces shootouts, drug overdoses

Live amongst no roses, only the drama, for real

My pen taps the paper then my brain’s blank

I see dark streets, hustling brothers who keep the same rank

Pumping for something, some’ll prosper, some fail

Judges hanging niggas, uncorrect bails for direct sales

My intellect prevails from a hanging cross with nails

Things have changed from the days when Nas lived there. Since the 2000s, crime in Queensbridge, along with the rest of NYC, has decreased, but is still higher than in many places around the city. The median income today is between $21,000 and $25,000 a year, and the average rent is less than $500.

Queensbridge fits a common pattern of poor urban neighborhoods during the 20th century that has been well-researched by sociologists. In his 1987 book, The Truly Disadvantaged: The Inner City, The Underclass, and Public Policy, William Julius Wilson, a Harvard professor focused on urban communities, introduced the concept of “concentrated poverty” – a poverty incidence of 40% or greater, which has since become the de facto threshold for sociological research around urban ghettos. He argued that concentrated poverty creates “social isolation”, in which the community has fewer interactions with mainstream society, and, as a result, limited access to job networks and economic opportunities. With fewer opportunities to earn a living, people in poor communities are more likely to turn to crime as an alternative.

Share of the poor population living in neighborhoods with poverty rates of 40 percent of higher, 2008-2012.

(Source: Brookings Institution)

According to Wilson, there are a number of reasons for the high proportion of blacks and Hispanics in communities marked by concentrated poverty. First and perhaps foremost to this discussion, overt systemic racial discrimination and segregation pushed more minorities into the inner cities:

Blacks were discriminated against far more severely in the early twentieth century than were the new white immigrants. Through restrictive covenants, municipal policies, and federal housing programs, blacks, unlike other immigrant groups, were forced into particular areas inner cities. At the same time blacks were discriminated far more severely than other groups in the labor market making them disproportionately poor and concentrated in low-paying jobs, particularly in the industrial sector. Collectively these forms of racial and spatial discrimination laid the basis for most areas of contemporary concentrated poverty.

Later on in the twentieth century, broad societal changes that I describe in another post, “The Convergence: America’s Long Arc of Development”, ushered in a period of de-industrialization, reducing the number of low-wage jobs available to blacks, while white flight and “spatial mismatch”, which describes the expanding geographic rift as economic growth shifted from the cities to the suburbs, all led to the further decline of urban ghettos.

This is exactly what happened to Queensbridge. The shift to a low-income housing project in the 50’s increased racial segregation in the community and declining socioeconomic conditions intensified, causing violent crime to increase. The escalation of the war on drugs during the Reagan Era only exacerbated the situation, and Queensbridge became a more dangerous place than ever.

The result for communities like Queensbridge is a decades-old poverty trap, in which social isolation and declining economic opportunities make it increasingly difficult for the overwhelmingly minority inhabitants to pull themselves out of poverty, creating a permanent underclass. And for people like Anthony, fewer economic opportunities put pressure on them to support their families in other ways. When drug dealing is ubiquitous in a community, it becomes an attractive proposition for someone without a lot of options.

Institution 5: The Schools

Poverty does not only lead to more crime in neighborhoods like Queensbridge. It affects just about every institution that is built in and around the community. The Brookings Institution explains some of the other ramifications of concentrated poverty:

Poor individuals and families are not evenly distributed across communities or throughout the country. Instead, they tend to live near one another, clustering in certain neighborhoods and regions. This concentration of poverty results in higher crime rates, underperforming public schools, poor housing and health conditions, as well as limited access to private services and job opportunities.

We have covered higher crime rates and limited access to private services and job opportunities, so let’s turn our focus to the underperforming public schools. In the U.S., funding for public schools comes from local property taxes. As the poverty level creeps up, housing prices decline dramatically. According to one study, once the poverty level in a community exceeds 10%, housing and rental prices steeply decline until it reaches the 40% threshold of concentrated poverty, at which point prices level out.

Since property taxes are calculated using housing prices, schools in poor communities have fewer resources available than those in more affluent communities, where housing prices are higher. This systemic problem, coupled with limited job opportunities for high school graduates due to spatial mismatch, fewer mentors to provide positive guidance, and the high prevalence of crime in and around the schools, results in an inferior education for children in areas of concentrated poverty, leaving them ill-prepared to succeed, further widening the income divide and compounding socioeconomic inequality.

In New York City, spending on a pupil in a neighborhood with 30% poverty is 11% less than in one with very little poverty.

I have covered the tragedy of the American education system ad nauseum in this blog, and have discussed the importance of education for economic development in several posts. Without a decent education, generations of children born into poverty have few opportunities to break the cycle of poverty, keeping them ensnared in a vicious cycle of poverty that all too often ends with prison.

It is impossible to say whether a strong public school system would have set Anthony on a different path. But the purpose of education is to give children the tools to succeed and skills to find employment. Without a good education, the opportunities are limited.

III. Conclusion

Let’s take a step back and review the each of the institutions, starting at the beginning. Anthony is arrested, tried, and convicted of dealing drugs, after being stopped-and-frisked on a project corner. His neighborhood, Queensbridge, is poor and overwhelmingly black and Hispanic. The school system is underfunded, the community is isolated, and few economic opportunities exist for young people, increasing the likelihood that they join a gang, either to earn money from selling drugs or simply for protection. Anthony gets caught up in the life and goes to jail, leaving his girlfriend without a breadwinner and son without a father.

Now we can generalize his experience more broadly. Historical racial segregation and discrimination and the changing dynamics of the American economy led to concentrated poverty and increasing social isolation in urban ghettos, the majority of whose inhabitants are black and, more recently, Hispanic. Higher levels of poverty drive down housing prices, which deprive the community of property taxes, which creates an inferior school system for black children and prevents poor urban communities from improving.

Those inhabitants have fewer economic opportunities and are more likely to turn to crime as a way of making ends meet. Crime becomes increasingly concentrated in these communities, leading to a greater police presence and higher rates of arrest. Various factors, including generic racial bias, politicians’ fears of being labeled soft on crime, and the disproportionate media coverage of black criminality, leads to policies like mandatory sentencing that unfairly result in longer sentences for people of color. And all of these factors combined result in an incarceration rate of six times that of white people, which is right where we started.

In this essay, I have tried to break down the infinitely complex systems that govern individuals and highlight how systemic institutional racism pervades every aspect of society. This racism is not overt, and it is not sensational. It is not a white police officer shooting an unarmed black teenager and leaving him to die in the streets. It is not a bunch of white fraternity members chanting racial epithets on a bus. It is not spoken, nor is it perpetrated by any one individual. This racism is built into the very fabric of our society, creating a permanent underclass that is overwhelmingly black and Hispanic. And it is getting worse.

I don’t know the answer to this problem. I fear that it is so ingrained into our society that we cannot diagnose, much less eliminate, the disease. As a society, we must be be willing to engage in collective self-criticism that makes most people uncomfortable. Whenever a politician tries to have an honest conversation about systemic racial inequality, they risk being labeled an apologist for America. And, unfortunately, in every society, the underclass, despite having the numbers, rarely has the political influence or money to effect real pro-poor policies.

I welcome the discussion about race that the the events of the last year have forced America to have. But as long as we focus on the symptoms, rather than the disease, the problem will only continue to get worse.

Develop Economies’ Music Recommendation

Now, just for full disclosure, I know the founder of M-Prep, Toni Maraviglia, from my time in Nairobi. We briefly worked together at Bridge, where she developed the school manager and teacher training materials. A Teach for America alum, business school dropout, and true social entrepreneur, Toni discovered while developing an

Now, just for full disclosure, I know the founder of M-Prep, Toni Maraviglia, from my time in Nairobi. We briefly worked together at Bridge, where she developed the school manager and teacher training materials. A Teach for America alum, business school dropout, and true social entrepreneur, Toni discovered while developing an  MPrep helps kids learn, review, compete and collaborate through accessible and fun mobile applications. We also give teachers data about their students and help parents stay informed – all on simple mobile tech. Basically, we make it easy and fun for an educational community to communicate and share information.

MPrep helps kids learn, review, compete and collaborate through accessible and fun mobile applications. We also give teachers data about their students and help parents stay informed – all on simple mobile tech. Basically, we make it easy and fun for an educational community to communicate and share information.

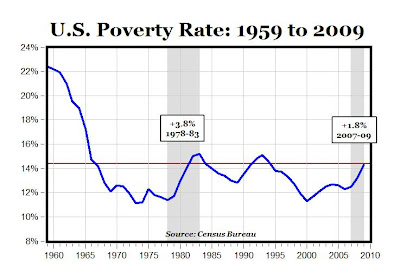

In the wake of the recession, with so many people currently unemployed, the poverty level in the U.S. continues to grow. And, while Edelman’s diagnosis is right, the fixes for at least some of the problems seem more difficult. The number of low-wage jobs in America reflects the spread of globalization and the movement of jobs overseas. This process has been ongoing for several decades, as manufacturing steadily moved abroad and, increasingly service industries, like call centers and business process outsourcing, followed suit. Ironically, America’s loss became the developing world’s gain, as hundreds of millions of people climbed above the poverty line in places like China, India, Brazil, and the Philippines. On a global scale, the trend toward low-wage jobs in the United States may actually reflect a global poverty reduction trend.

In the wake of the recession, with so many people currently unemployed, the poverty level in the U.S. continues to grow. And, while Edelman’s diagnosis is right, the fixes for at least some of the problems seem more difficult. The number of low-wage jobs in America reflects the spread of globalization and the movement of jobs overseas. This process has been ongoing for several decades, as manufacturing steadily moved abroad and, increasingly service industries, like call centers and business process outsourcing, followed suit. Ironically, America’s loss became the developing world’s gain, as hundreds of millions of people climbed above the poverty line in places like China, India, Brazil, and the Philippines. On a global scale, the trend toward low-wage jobs in the United States may actually reflect a global poverty reduction trend. Those jobs are not coming back. Edelman suggests investing more heavily in education and skill development, and I agree. Because the funding source is local, our current public education system is failing to educate huge swathes of the population in a vicious cycle that creates a poverty trap. Setting aside the fact that discriminating on the basis of zip code is

Those jobs are not coming back. Edelman suggests investing more heavily in education and skill development, and I agree. Because the funding source is local, our current public education system is failing to educate huge swathes of the population in a vicious cycle that creates a poverty trap. Setting aside the fact that discriminating on the basis of zip code is