The other day, I talked about the first of the four reasons why we cannot end poverty in the United States. Now I will talk about the other three.

The other day, I talked about the first of the four reasons why we cannot end poverty in the United States. Now I will talk about the other three.

Single parenthood is another challenge. According to Edelman, poverty rates among families led by single mothers is an astonishing 40%. I don’t know enough about the problem to propose any solutions. In the past, I have discussed how the the problem is systemic and self-reinforcing. But, from a policy perspective, I am not sure there is much that can be done. And race and gender are also big problem. There are certainly policy prescriptions here, but the issue is so systemic that I won’t even try to address them in this post.

The last reason – the reduction of the safety net and elimination of certain assistance programs – is really troubling however. Edelman explains the implications:

The census tells us that 20.5 million people earn incomes below half the poverty line, less than about $9,500 for a family of three — up eight million from 2000.

Why? A substantial reason is the near demise of welfare — now called Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, or TANF. In the mid-90s more than two-thirds of children in poor families received welfare. But that number has dwindled over the past decade and a half to roughly 27 percent.

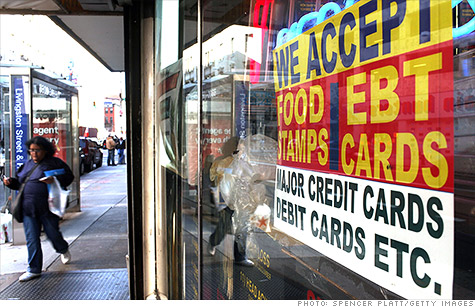

One result: six million people have no income other than food stamps. Food stamps provide an income at a third of the poverty line, close to $6,300 for a family of three. It’s hard to understand how they survive.

At least we have food stamps. They have been a powerful antirecession tool in the past five years, with the number of recipients rising to 46 million today from 26.3 million in 2007. By contrast, welfare has done little to counter the impact of the recession; although the number of people receiving cash assistance rose from 3.9 million to 4.5 million since 2007, many states actually reduced the size of their rolls and lowered benefits to those in greatest need.

During a recession, expanding the food stamp program and other TANF programs provide the greatest ROI in terms of stimulating demand. Unlike the stimulus checks of 2008, which most people used to pay down debt and squirrel away in a savings account, food stamps and other credits are spent immediately. Aside from the fact that we, as a country, have an obligation to make sure that people can eat, these programs make sense from an economic recovery standpoint.

The chart on the right shows spending on low-income programs, with and without Medicare and Social Security, as a percentage of real GDP over time. In the War on Poverty during the LBJ administration, federal spending increased significantly before leveling off until the recession in 2008. It has increased since Obama took office, primarily in response to the downturn, which increased the rolls of people in need. Despite this mini-surge in spending, there a danger that it could be reversed.

The chart on the right shows spending on low-income programs, with and without Medicare and Social Security, as a percentage of real GDP over time. In the War on Poverty during the LBJ administration, federal spending increased significantly before leveling off until the recession in 2008. It has increased since Obama took office, primarily in response to the downturn, which increased the rolls of people in need. Despite this mini-surge in spending, there a danger that it could be reversed.

Edelman ends the article with a stark warning that the status quo, as inadequate as it is, may not last. There are long-term ways of dealing with the growing income and wealth gaps – simplifying the tax code, allowing the Bush tax cuts to expire, increasing the capital gains tax, regulating financial institutions, and investing in education and infrastructure, to name a few. But an easy short-term solution is to, at the very least, maintain the current TANF programs, if not expand them to include the growing numbers of people living at or below the poverty line in this country.

Poverty in this country is a challenge. But we can deal with the problem by reforming our education system and maintaining and potentially expanding the social safety net.

Develop Economies’ Music Recommendation

In Uganda, on the other hand, HIV could very much be a death sentence, particularly for the poor. Anti-retrovirals are

In Uganda, on the other hand, HIV could very much be a death sentence, particularly for the poor. Anti-retrovirals are

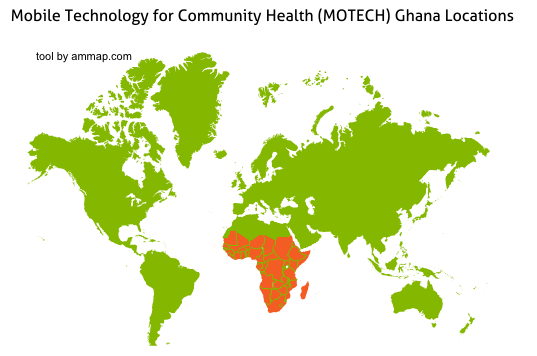

If you are a pregnant woman in the Upper East region of Ghana who has registered with MOTECH, you will receive this message during the fifth week of your pregnancy. Started in 2009, MOTECH is an mHealth platform created in partnership between the Ghana Health Service, Grameen Foundation, and Columbia Mailman Public Health School, with funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. It is designed to facilitate better medical information dissemination to rural areas and improve operational efficiency at community- and district-level health centers in one of the poorest regions of the country.

If you are a pregnant woman in the Upper East region of Ghana who has registered with MOTECH, you will receive this message during the fifth week of your pregnancy. Started in 2009, MOTECH is an mHealth platform created in partnership between the Ghana Health Service, Grameen Foundation, and Columbia Mailman Public Health School, with funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. It is designed to facilitate better medical information dissemination to rural areas and improve operational efficiency at community- and district-level health centers in one of the poorest regions of the country.