This is part two of a two-part post about the Obama administration’s approach to foreign policy and military intervention in Africa and the Middle East.

The other day I discussed the first four points of Obama’s approach to military intervention – be effective, follow international law, put no American troops on the ground, and multilateralism. Today I will talk about the last one: having a clearly-defined goal.

This is the most important tenet of all. In Iraq, the U.S. overthrew Saddam and remarkably never planned for phase two. In Libya, all possible post-Gaddafi scenarios were taken into account to understand exactly what we were getting ourselves into. Not too far from where I live in Kenya, Obama just deployed 100 special forces “advisers” to hunt for Joseph Kony, the terrible leader of the Lord’s Resistance Army, a Ugandan paramilitary organization that has killed 30,000 people throughout Central Africa over the last two years. The objective is simple: find and kill Joseph Kony and eliminate the LRA forever. Unlike Islamic extremists, they have little support from the local population, and most of the world agrees that the world will be a much better place with Joseph Kony no longer among the living.

This is the most important tenet of all. In Iraq, the U.S. overthrew Saddam and remarkably never planned for phase two. In Libya, all possible post-Gaddafi scenarios were taken into account to understand exactly what we were getting ourselves into. Not too far from where I live in Kenya, Obama just deployed 100 special forces “advisers” to hunt for Joseph Kony, the terrible leader of the Lord’s Resistance Army, a Ugandan paramilitary organization that has killed 30,000 people throughout Central Africa over the last two years. The objective is simple: find and kill Joseph Kony and eliminate the LRA forever. Unlike Islamic extremists, they have little support from the local population, and most of the world agrees that the world will be a much better place with Joseph Kony no longer among the living.

Some argue that deploying more troops in yet another war with little strategic interest to the United States is a bad idea. In one sense, these people are right – Joseph Kony and the LRA pose no direct threat to the United States. They may have a nightmarish record of human rights violations, but their wrath is confined to the unfortunate villages that happen to reside between point A and point B on the LRA’s marching path. But these detractors don’t really see the big picture.

Ugandan peacekeepers in Somalia

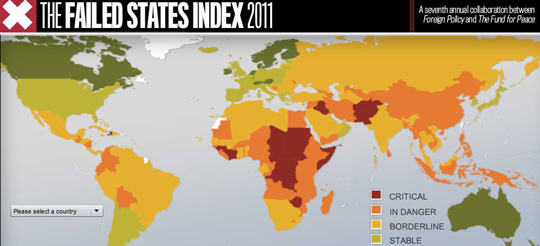

Al Shabab, unlike the LRA, and Somalia in general are potentially very big problems for the United States. It is the most failed state in the world and is a stone’s throw from Yemen and the Arabian Peninsula – a hotbed of terrorist activity. The only thing preventing Somalia from completely collapsing (as opposed to almost completely collapsing, which is where it is now) and falling entirely into the hands of Al Shabab is the Ugandan peacekeeping force fighting in Mogadishu (with significant help from the U.S. and Europe). Ingratiating ourselves to the Ugandan people by helping to eradicate the group that has caused so much suffering, and eliminating a destructive force – the LRA – will help stabilize the region, helping to prevent the turmoil in Somalia from spilling into other nations. So, at the end of the day, destroying the LRA is probably as much about fighting terrorism as it is a humanitarian mission.

This is smart power. In the chess match of foreign policy, Obama thinks several steps ahead of his opponents, recognizing the link between Joseph Kony terrorizing Uganda and Somalia becoming the new Waziristan. He assesses the potential sacrifices, in blood and treasure, and carefully considers the outcomes. In an op-ed titled “Stop Searching for an Obama Doctrine,” Fareed Zakaria explains why pragmatism trumps blind ideology in the way Obama views the world:

God bless the President

So what is the Obama Doctrine?

In fact, the search itself is misguided. The doctrinal approach to foreign policy doesn’t make much sense anymore. Every American foreign policy “doctrine” but one was formulated during the Cold War, for a bipolar world, when American policy toward one country — the Soviet Union — dominated all U.S. strategy and was the defining aspect of global affairs. (The Monroe Doctrine is the exception.) In today’s multipolar, multilayered world, there is no central hinge upon which all American foreign policy rests. Policymaking looks more varied, and inconsistent, as regions require approaches that don’t necessarily apply elsewhere.

Obama does, however, have a worldview, a well-considered approach to international affairs. His views have been straightforward and consistent. From the earliest days of his presidential campaign he said that he sees the basic argument in American foreign policy as “between ideology and realism” and placed himself squarely on one side.

What marks administration policy is a careful calculation of costs and benefits. The great temptation of modern American foreign policy, from Versailles to Vietnam to Iraq, has been to make grand declarations — enunciate doctrines — that then produce huge commitments and costs. We are coming off a decade of such rhetoric and interventions and are still paying the price: more than $2?trillion, not to mention the massive cost in human lives. In that context, a foreign policy that emphasizes strategic restraint is appropriate and wise.

I agree with Fareed on all of his points except one (which makes me nervous, since I agree with 100% of what he usually says, which means that, if history is a guide, I am wrong). I think that the five points above collectively comprise the Obama doctrine, or at least something close to it. Just because the Bush Doctrine was particularly jingoistic doesn’t mean a doctrine based on “strategic restraint” – one marked by define goals, multilateralism, limited U.S. involvement, etc. – isn’t a doctrine. In fact, Obama received a lot of criticism for “leading from behind.” But not only is a strategy – contrary to what some believe – it is an effective one. Back to theRolling Stone article:

“It isn’t leading from behind,” says Anne-Marie Slaughter, the former head of policy planning at the State Department, rejecting a quote in The New Yorker by an unnamed Obama adviser that came to dominate the debate over Libya. “We created the conditions for others to step up. That exemplifies Obama’s leadership at its best. The world is not going to get there without us – and we did it in a way where we’re not stuck, or bearing all the costs.”

If Obama gets another four years – Insha’allah – I would expect that all future military interventions stand up to the test of these five points – a retroactive rubric, of sorts. And that, I think, is what a doctrine is all about.

DEVELOP ECONOMIES MUSIC RECOMMENDATION