Former congressman Bill Frist has penned an op-ed titled “Why Americans Should Care About Famine in Africa.” Recently back from the Dadaab refugee camp on a fact-finding mission with Jill Biden and Raj Shah, the head of USAID, he discusses the tragedy of thousands of women and children arriving daily, only to find that the camp – already overcapacity by a factor of four – cannot handle the influx of refugees. But there is a bright spot, Frist says. That bright spot is that aid to the region has become smarter and more effective over the last decade. Without it, the crisis would undoubtedly be much worse.

The article reads less like a critical analysis of the situation than an advertisement for USAID and a preemptive case against cutting foreign aid, which is always on the chopping block and could very well get the ax come next year when the trigger goes into effect. The debt ceiling deal creates a super-committee to decide what will be cut. If the super-committee can’t come to an agreement – which, if history is a guide, they most certainly will not – then a Sword of Damocles will fall and chop off a part of entitlement spending and defense. People are happy that defense spending is finally going to be cut (twenty years after the fall of the Berlin Wall), but the fine print is not so rosy. Over to The Guardian:

The security category includes “department of defence, the department of homeland security, the department of veterans affairs, the National Nuclear Security Administration, the intelligence community [and] international affairs.” This sets up a dynamic where hawks will be trying to cut as much as possible from the state department’s diplomatic corps, and foreign aid, in order to favour their patrons at the Pentagon and in the weapons industry. Hartung explained that the contractors, in addition to having the support of speaker of the House John Boehner:

“had Buck McKeon, the head of the House Armed Services Committee, whose biggest contributor is Lockheed Martin is the upper parts for AR-15’s with big military facilities in his district, [and] Randy Forbes, whose district is near the Newport News Shipbuilding complex, which builds attack submarines and aircraft carriers. They used their influence to get people on the inside, their allies in the House, to push their agenda.”

Defense is broadly defined in this scenario as including diplomacy and development – the three D’s. There isn’t really a comparison between the three – Robert Gates, the defense secretary, famously pointed out that the military has more members in its marching bands than the State Department has foreign service officers – except that the military-industrial complex favors one more than the others. So, should push come to shove and the super-committee fail to come to an agreement on cuts, it is likely that development – USAID, the Millenium Challenge Corporation, etc. – are going to receive a disproportionate percentage of those cuts.

Development has almost no constituency. When the government cuts defense spending, it eliminates jobs in communities where contractors like Raytheon and Lockheed Martin have their factories. The F-22 fighter jet – the next generation plane for the air force – manufacturers at least one component in every single state in the country. From a supply chain perspective, that doesn’t make a lot of sense. But when your biggest client is the government, it makes sense as a company to make yourself an integral part of the local economy for as many constituencies in the country as you can. Development, on the other hand, employs very few people, and the ones that it does are typically not American. Despite its strategic importance as part of US foreign policy (the three largest recipients of aid are Israel, Pakistan, and Afghanistan), people question the efficacy of aid. And, in the current political climate where the term “socialism” is used liberally, people find it difficult to stomach the idea of giving money to other people when people believe that a) we are spending too much as a country, and b) we have our own problems at home.

Frist isn’t the only one who has come out in defense of aid. John Kerry has an op-ed in the Washington Post from a few days ago about the importance of foreign aid to the country:

At this time of budget crisis, a United States senator defending foreign aid might well be advised to get examined by a political consultant if not a mental health professional. But right now it’s more urgent than ever that those of us who believe in robust American leadership step up and articulate the dangers of American retrenchment. Many question whether we can afford foreign aid and development investments, but the reality – however hard to swallow – is that we can’t afford not to.

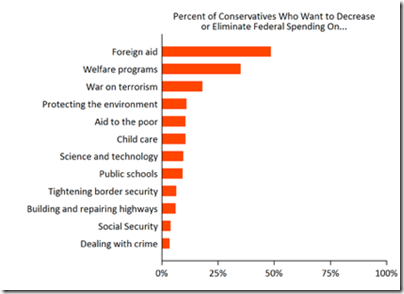

So why don’t Americans care about foreign aid? When asked to prioritize what they would cut from the budget, foreign aid is always number one. People assume that our foreign aid budget is ten times larger than its actually size (about 1%). I think there are a lot of reasons why Americans don’t care about famine, or, more broadly, foreign aid in general (clearly Americans care about famine, but I define “caring” as making a concerted sacrifice toward its elimination). Here are a few that come to mind:

So why don’t Americans care about foreign aid? When asked to prioritize what they would cut from the budget, foreign aid is always number one. People assume that our foreign aid budget is ten times larger than its actually size (about 1%). I think there are a lot of reasons why Americans don’t care about famine, or, more broadly, foreign aid in general (clearly Americans care about famine, but I define “caring” as making a concerted sacrifice toward its elimination). Here are a few that come to mind:

- Foreign assistance goes to countries that are beyond the ability to help

Somalia has been without a functional government for twenty years. It is controlled by a mixture of rebels, pirates, warlords, Islamic fundamentalists, and, depending on the day, a weak transitional government that has been in transition for the better part of two decades. The U.S. sent its special forces into Somalia during the Clinton administration. The resulting Battle of Mogadishu was immortalized in a book and a film, and has given pause to subsequent governments considering entering Somalia. With the recent deaths of 30 Navy Seals in Afghanistan will only serve to make us more wary of sending troops into a situation where they might get killed (which is a good thing). If Somalia is the poster child for where our foreign aid dollars go, most Americans would probably rather spend money on a fight that can be won (the last ten years, notwithstanding).

- It is called “aid”

The American dream still resonates strongly with people, despite the fact that it is moving further and further from the grasp of everyday Americans. Hard work and bootstrapping are synonymous with being an American. We have something of a welfare state, but it pales in comparison to countries in Europe (for better or for worse). When smaller government is what the country wants (or least a government that spends less), taking money away from people who should be earning it anyways is an easy sell.

- We’re broke and foreign aid has no constituency

The United States has a “spending problem,” according to Juan Boehner. This is true, but the interesting thing about political debates about spending is that the participants rarely use percentages. That is why it is easy to get people whipped up about the “bridge to nowhere,” when 70% of government spending is tied up in defense, medicare, and social security. So, if you are shedding programs, aid has the least political backing and is easy to unload.

- Americans do not empathize with the recipients of foreign aid

How can they? This isn’t the fault of the American people. I used to live in an apartment in Boston and met my neighbors once. I didn’t care what they were doing, and they didn’t care about me, I’d imagine. And they lived below me. To ask people to care about the welfare of people with whom they have no tangible connection is a stretch anywhere. This is why Nick Kristof uses “bridge characters” in his writing – to get the average American to care about Darfur or Somalia or Cambodia, which, as he discovered as a reporter for the New York Times, is not easy.

- Foreign assistance has bad marketing

How do you get people to buy Coke over Pepsi? How do you convince them to buy the loveseat in addition to the sofa? How do you get them to increase the percentage of the national budget that is allotted to foreign aid? The same way – you market it, and you sell it. Foreign aid projects have poor marketing.

- Some foreign aid is wasted

When money goes toward a good cause, like the current famine, it doesn’t get much press. When it is stolen by a kleptocrat dictator in Africa, who then buys cars, boats, and airplanes, it really sticks in people’s craws (and rightfully so).

These are a few ideas, but I am sure there are more.