Old habits die hard, and the motor patterns in my fingers that brought me to the Drudge Report so many times when I worked in a cubicle in Boston once again led me to page the other day. Living up to its reputation for sensationalism, it featured a headline recently about the escalation of food prices around the world. Unfortunately, while Drudge is usually over-the-top, rising food prices are no laughing matter. In 2008, the rising cost of our daily bread led to food riots around the globe and massive destabilization in developing countries, most prominently in Haiti. It alerted food-dependent developed countries to a glaring Achilles’ heel, spurring a land grab in Africa that (almost) comically culminated with the South Korean conglomerate Daewoo making a bid for half – yes, half – of the arable land in Madagascar. So when the next food crisis hits, and hit it will, the developed countries with a foothold may think they are food-secure, until the hungry populations of the food-insecure countries serving as their respective breadbaskets see the fields of gold beyond the fence and decide to Mugabe it for themselves. Unless, of course, the landowners (read: nations) deploy armed guards to protect these critical investments, resulting in rioting, bloodshed, and, inshallah, the toppling of governments.

Old habits die hard, and the motor patterns in my fingers that brought me to the Drudge Report so many times when I worked in a cubicle in Boston once again led me to page the other day. Living up to its reputation for sensationalism, it featured a headline recently about the escalation of food prices around the world. Unfortunately, while Drudge is usually over-the-top, rising food prices are no laughing matter. In 2008, the rising cost of our daily bread led to food riots around the globe and massive destabilization in developing countries, most prominently in Haiti. It alerted food-dependent developed countries to a glaring Achilles’ heel, spurring a land grab in Africa that (almost) comically culminated with the South Korean conglomerate Daewoo making a bid for half – yes, half – of the arable land in Madagascar. So when the next food crisis hits, and hit it will, the developed countries with a foothold may think they are food-secure, until the hungry populations of the food-insecure countries serving as their respective breadbaskets see the fields of gold beyond the fence and decide to Mugabe it for themselves. Unless, of course, the landowners (read: nations) deploy armed guards to protect these critical investments, resulting in rioting, bloodshed, and, inshallah, the toppling of governments.

And now, it could be happening again. I sound like Drudge.

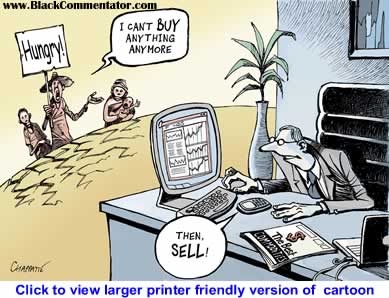

Theoretically, commodity prices fluctuate based on the principles of supply and demand. When the demand for grain exceeds supply, prices go up. In the movie Trading Places, Randolph and Mortimer Duke, the lovable racist WASPs, try to corner the market for Florida oranges. They pay Clarence Beeks for an advance copy of the classified crop report, which will determine the price of oranges for the next trading period. Akroyd and Murphy intercept the report and forge a new version, giving the impression that there will be a shortage of oranges due to a long winter. On the trading floor, the Dukes’ trader buys as many orange futures as he can, under the assumption that they will become more valuable once the negative forecast for oranges is released. The other traders see what is happening, and also buy, driving prices up and up. Akroyd and Murphy begin selling at 120, until the crop report is released. When the real crop report is released, which says that this year’s orange yields will be high, the price plummets, and Akroyd and Murphy buy all the futures they sold in the morning, becoming millionaires in the process. This is how commodity trading works.

In reality, this isn’t always the case. Prices for agricultural commodities, like those of oil, gold, cocoa, pork bellies, and everything else traded on the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, are subject to the nefarious forces of speculation.

The June 2009 issue of Harper’s magazine featured an article from Frederick Kaufmann titled “The Food Bubble: How Wall Street starved millions and got away with it.” I suggest you read the piece in its entirety if you want to learn the intricacies of global food trade and understand why, in a world of eternal food surpluses, a billion people can go hungry every year. But for my casual readers, Develop Economies will break it down as best he can.

The June 2009 issue of Harper’s magazine featured an article from Frederick Kaufmann titled “The Food Bubble: How Wall Street starved millions and got away with it.” I suggest you read the piece in its entirety if you want to learn the intricacies of global food trade and understand why, in a world of eternal food surpluses, a billion people can go hungry every year. But for my casual readers, Develop Economies will break it down as best he can.

Basically, in 1991 Goldman Sachs realized that there was money to made in food commodities, and created the Goldman Sachs Commodity Index. The index contained 18 commodities, including cocoa, coffee, cattle, wheat, and others. Once investors realized that they could park their money in a safe, relatively un-volatile investment like that, other firms began offering their own food commodity indexes. The principle behind commodity exchanges is to allow for hedging. Buy low, sell high. Farmers can guarantee a market for their grain and buyers can lock in favorable price in advance. The system depends on the receipt of the final product, however. Not so in the Goldman Sachs Commodity Index. Kaufmann explains:

Clearly, some innovation was in order. In the midst of this dead market, Goldman Sachs envisioned a new form of commodities investment, a product for investors who had no taste for the complexities of corn or soy or wheat, no interest in weather and weevils, and no desire for getting into and out of shorts and longs—investors who wanted nothing more than to park a great deal of money somewhere, then sit back and watch that pile grow. The managers of this new product would acquire and hold long positions, and nothing but long positions, on a range of commodities futures. They would not hedge their futures with the actual sale or purchase of real wheat (like a bona-fide hedger), nor would they cover their positions by buying low and selling high (in the grand old fashion of commodities speculators). In fact, the structure of commodity index funds ran counter to our normal understanding of economic theory, requiring that index-fund managers not buy low and sell high but buy at any price and keep buying at any price. No matter what lofty highs long wheat futures might attain, the managers would transfer their long positions into the next long futures contract, due to expire a few months later, and repeat the roll when that contract, in turn, was about to expire—thus accumulating an everlasting, ever-growing long position, unremittingly regenerated.

You can see some of these dynamics on a local level in Ghana, where the price of maize fluctuates from 20 cedis per bag at the end of the major season, when farmers who cannot afford to store their crops are forced to sell amidst a glut of maize, to 100 cedis during the lean season, when maize is scarce and the more business-minded traders release their stores of maize into the system. Again, the system depends on the buyer eventually taking receipt of the product. But in the Goldman Sachs Commodity Index, the strategy is to buy…and buy, and buy some more. In other words, the goal is to corner the market.

It is certainly an admirable financial product. So much so that the amount of money parked in commodity index funds went from a paltry $13 billion in 2003 to $317 billion in 2008. Unfortunately, we live in a zero sum world, particularly when it comes to financial innovation. And, on the losing end, you find the people that usually end up on the losing end: the poor. In 2008, a billion more people went hungry, including 49 million Americans. Food prices around the world skyrocketed, increasing by 80% between 2005 and 2008. In other words, in 2008, it cost nearly double to put a loaf of bread on the table.

It is certainly an admirable financial product. So much so that the amount of money parked in commodity index funds went from a paltry $13 billion in 2003 to $317 billion in 2008. Unfortunately, we live in a zero sum world, particularly when it comes to financial innovation. And, on the losing end, you find the people that usually end up on the losing end: the poor. In 2008, a billion more people went hungry, including 49 million Americans. Food prices around the world skyrocketed, increasing by 80% between 2005 and 2008. In other words, in 2008, it cost nearly double to put a loaf of bread on the table.

To be fair, Kaufmann has a one-sided view and somewhat one-dimensional take on a very, very complex issue. There are other causes attributed to the crisis. For example, rising oil prices (coincidentally, also due to rampant speculation on the part of the same financial-services overlords) led to higher fertilizer and other input prices, increasing the cost of production and the price of wheat around the world. Steve Strongin, Head of Global Investment Research, issued a letter to Harper’s defending the Goldman Sachs Commodity Index and offering his two cents on why the rising price of food destabilized the world:

Commodity index funds provide the futures markets with a stable pool of capital that improves the ability of farmers to insure themselves against the risks inherent in agricultural prices, which can allow them to produce more food at a lower cost.

Long-term trends, including increased meat consumption by the growing middle class in the emerging markets and the increased use of biofuels in the developed markets, have created a backdrop for global food shortages and, as a result, millions are left desperately exposed to the vagaries of the weather for their survival.

No doubt these factors contributed to the crisis. The agriculture-industrial complex created a huge market for corn in biofuels, and the taste for meat around the world increased, particularly at #4 146 West Concord Street after the Gaslight Restaurant opened in the South End and started serving the best steak frites in Boston for only $19. But, as Kaufman points out, a shortage of wheat was never the problem:

The wheat harvest of 2008 turned out to be the most bountiful the world had ever seen, so plentiful that even as hundreds of millions slowly starved, 200 million bushels were sold for animal feed. Livestock owners could afford the wheat; poor people could not. Rather belatedly, real wheat had shown up again—and lots of it. U.S. Department of Agriculture statistics eventually revealed that 657 million bushels of 2008 wheat remained in U.S. silos after the buying season, a record-breaking “carryover.” Soon after that bounteous oversupply had been discovered, grain prices plummeted and the wheat markets returned to business as usual.

So, when food commodity futures are traded, they, like oil futures and cocoa futures, are subject to the forces of speculation. But, unlike cocoa, which really only affects the price of chocolate, wheat is a staple commodity for the world. It is like trying to corner the market for water.

Kaufman closes with a few responses to his question about whether a major food crisis could happen in the future:

“Yes,” said Layne Carlson, corporate secretary and treasurer of the Minneapolis Grain Exchange, who then told me the two principles that govern the movement of grain markets: “fear and greed.”

“Fear and greed.” It sounds like a headline from Drudge.

Thank you for writing about this important topic.

The CFTC is currently accepting comments about their proposal for new speculative limits. To send a comment, go to http://stopgamblingonhunger.com/?p=977 and follow the instructions.

It’s important that the CFTC hear from as many people as possible. Up to now, it has mostly been Wall Street folks asking them to weaken the rules.

Pingback: My Homepage

‘It is like trying to corner the market for water.’

You say that as though that were bizarre, impossible, or otherwise not in the cards, but it’s precisely what they are doing. Oregon just passed legislation banning citizens from collecting rainwater; other states already have that law. Privatisation of water is already in place in many parts of the world and in some US states. Soon to be nationwide, no doubt.