For those who do not know, Nicholas Kristof is an incurable optimist who writes a column for the New York Times on aid, development, foreign policy, and all things related. In a video posted to his blog, he took questions from readers. The author of one development blog point out that most of Kristof’s articles follow a standard narrative that: “one that often focused on the foreign, typically American “savior” helping the poor Africans in need, to the exclusion of efforts of black Africans themselves to bring about change on the ground.” It is a good question, since most of the development workers in this world making things happen are locals, not foreigners. Here is Mr. Kristof’s response:

I do take your point. That very often I do go to developing countries where local people are doing extraordinary work, and instead I tend to focus on some foreigner, often some American, who’s doing something there.

And let me tell you why I do that. The problem that I face — my challenge as a writer — in trying to get readers to care about something like Eastern Congo, is that frankly, the moment a reader sees that I’m writing about Central Africa, for an awful lot of them, that’s the moment to turn the page. It’s very hard to get people to care about distant crises like that.

One way of getting people to read at least a few paragraphs in is to have some kind of a foreign protagonist, some American who they can identify with as a bridge character.

And so if this is a way I can get people to care about foreign countries, to read about them, ideally, to get a little bit more involved, then I plead guilty.

I think this is a pretty thoughtful and right-on response. He has obviously wrestled with the issue and it is something he has had to reconcile in his writing. The blogger, Texas in Africa, isn’t satisfied:

I’m really hard on Kristof, but it’s not without reason. Does he really believe that New York Times readers are only interested in good work being done by their fellow Americans? That we can’t relate to people on the other side of the world? Because to me, that seems insulting to the readership. Maybe I’m insulated from the need for a “bridge character” because of what I study this for a living. I feel a kinship and a desire to support people who are doing good things no matter what their background. Don’t you?

In the end, this answer is just another variant of the “good intentions are enough” mindset. It excuses stereotyping in the name of awareness, while assuming that Americans are too parochial to be able to recognize, relate to, and applaud the work of people whose names sound different from ours. It reveals much about Kristof’s approach to the people he profiles; as we’ve discussed here many times before, they’re more often characters than people.

Mr. Kristof, I think you can do better.

A fair rebuttal, since it is true that, by Kristof’s own estimation, he is selling a lot of good and deserving people short in order to highlight more marketable people who sell to his audience. But, in the end, I side with Kristof in this argument. His readership is that of the New York Times. He needs to write a column that appeals to the most possible people. I agree with Texas in Africa that a lot of Kristof’s readers can relate to people, regardless of their background. If what Kristof is saying is true – that most of his readers require a “bridge,” someone they can relate to, in order to be engaged in his topics – then I think he has the right approach.

Also, I don’t think he is insulting his readership either. Most Americans don’t really care about what is happening in other countries, particularly third-world countries that never really make it onto their radar. The New York Times readership and, in particular, people reading Kristof’s articles every week are probably a self-selecting group of socially-conscious progressive that are more attuned to the issues. But some of them are reading it because Kristof tells compelling and inspirational stories. I would guess that the latter population outweighs the former. And, from an impact standpoint, I think it is an unfortunate truth, but a truth nonetheless, that the “white man’s burden” narrative that Kristof is accused of spinning helps him to reach more people than he could otherwise.

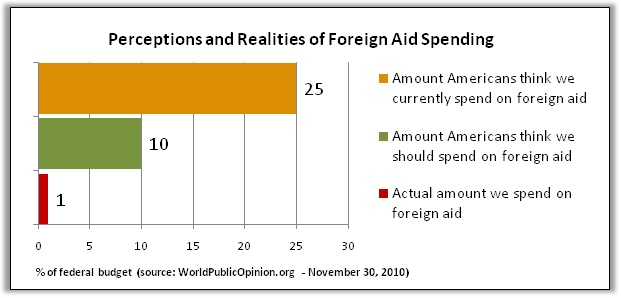

The American public is often polled about what they would most like to cut out of the federal budget, when budget cuts are necessarily. The results of one recent Economist/YouGOV poll are shown in the chart above. Since time immemorial, people disproportionately elect to cut foreign aid. This, despite the fact that foreign aid makes up less than 1% of the budget. Foreign aid has never been popular in this country. One major reason is that most people grossly overestimate how much we actually spend on it (see chart below). But part of the reason is that most people either don’t relate to the problems of recipient countries, or they just place domestic issues first. Also, when asked whether you would rather cut the defense budget or foreign aid (without knowing that they account for ~20% and ~1% of the budget, respectively), it is easy to choose the latter when do you really think about what that entails. Politicians and policy makers use information like this to decide which direction to take the country. Over to the Foreign Policy blog:

I can imagine that if Americans were asked about specific aid priorities — providing funds to build girls’ schools in Afghanistan, or to feed the hungry in Darfur, or build shelter for the homeless in Haiti — they would want to cut very few. How these questions get asked matters a lot — hence, why “aid to the poor” is so much more popular than much-maligned “welfare programs” in the chart above.

And who tells these stories better than Nicholas Kristof? If he can raise awareness about these “specific aid priorities” in countries that are off most people’s radar, even if it means selling short the locals making a difference, then I think that is a fair tradeoff. In another post, Texas in Africa disagrees:

I take a lot of heat for disliking Kristof’s writing. Most commenters argue that we should excuse Kristof’s sensationalism of victims of injustice since he has such a wide reach. “Isn’t it better that more people are aware of the crisis?” they argue.

Not if their awareness is based on falsehoods or incomplete truths. Kristof’s job as a reporter is to explain the parts of the world that the vast majority of his readers will never see. By always, only reporting on the worst of the worst, Kristof distorts reality. He may tell one person’s story, but as Shona points out, it’s not really even that person’s full story. In doing so, readers get an inaccurate picture of what life is like in the eastern Congo, the southern Sudan, or, I’d venture to guess, the brothels of India.

Bad facts lead to bad policy. This is why journalists’ sacred trust with the public is so important. Policy makers – most of whom will never go to or have a full understanding of these areas – read their stories. Because Kristof’s reach is so broad and because his columns run in one of the most important papers in the world, he does a terrible disservice to the very people he purports to help. Mr. Kristof, it’s time to show your subjects for what they are: people.

I think he is right that Kristof searches for textbook victimhood to highlight larger issues, perhaps distorting the reality of the situation. And I agree that bad facts lead to bad policy. But I highly doubt policymakers are taking their cues from Nicholas Kristof (if they are, that is a much larger issue). He is a story teller. If you are looking for a hardcore journalist, read Jeffrey Gettleman. Kristof’s value is to get people to care about issues they would normally know nothing about. By telling the stories that he does, he gets people to connect to these issues in a tangible way, which leads them to view them in specific rather than general terms. This might mobilize some political activism, leading to an increase in foreign aid dollars or government intervention or more funding from private donors. Maybe the next time a new Kristof reader is polled, they will think twice about slashing the foreign aid budget. And maybe if enough people rethink their views, it will be easier the next a bill comes from through the House and Senate regarding foreign aid and development assistance. I think both the characters and the real people on the ground that Kristof often neglects will appreciate that support, regardless of whether they get credit.

(Hat tip: Andrew Sullivan)

Pingback: Advice to the Amateurs: Ignore the Professionals - Develop Economies | Develop Economies