“There are two things that matter in politics. The first is money. I can’t remember the second.” – Mark Hanna

In December, a group calling itself the Republican Commissioners on the Financial Crisis Inquiry released a report titled the “Financial Crisis Primer,” which provides an explanation for economic crisis. According to the report’s authors, the big lenders, including the government, gave too many high-risk loans as part of a government-directed strategy to increase home ownership in the country. Because the price of housing never goes down (allegedly), creating a financial environment where everyone can afford to buy a home is a no-brainer, since the asset is guaranteed (almost) to increase in value over time.

Once all the credit-worthy, middle-income customers received loans to buy a house, lenders started to look to low-income population as a viable market. They started pushing subprime loans with introductory “teaser” rates that would eventual re-adjust and send the person who couldn’t really afford the house in the first place into bankruptcy. And the driving force behind this whole sequence of events was a social policy to increase asset ownership among the low-income segments of the population, otherwise known as the poor. This dynamic is explained here in the introduction to the Primer:

In the case of the government, it was following a social policy in addition to an investment policy. There were three important ways that the government pushed investors toward investing in mortgage debt. First, the regulatory capital requirements associated with mortgage debt were lower than for other investments. Second, the government encouraged the private market to extend credit to previously underserved borrowers through a combination of legislation, regulation, and moral suasion. Third, and most important, during the bubble’s expansion, the largest investors in the mortgage market, the government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs)—Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac—were instruments of U.S. government housing policy.

The argument is pretty much what you would expect from Douglas Holtz-Eakin, John McCain’s economic advisor during the 2008 presidential campaign and the man who famously coined the phrase “arugula-eating liberals” to describe Obama’s supporters. Blaming government social policies for the financial crisis is nothing really new, though this report formalizes the argument.

Simon Johnson, the former head of the IFC, takes issue with the report in an article from the blog Project Syndicate, titled “Did the Poor Cause the Crisis?” An MIT economist named Daron Acemoglu released a counter to the Republican Commisioners, explaining that, over the past forty years, the political elite has never really taken the needs of the low-income segments of the population into account when drafting legislation. The increasing influence of the private sector through lobbyists and the revolving door between Washington and Wall Street has much more to do with influencing financial regulation than does a poor government social policy designed to help the poor. Johnson explains:

Acemoglu’s assessment of recent research on lobbying is that parts of the private sector wanted financial rules to be relaxed – and worked hard and spent heavily to get this outcome. The impetus for a big subprime market came from within the private sector: “innovation” by giant mortgage lenders like Countrywide, Ameriquest, and many others, backed by the big investment banks. And, to be blunt, it was some of Wall Street’s biggest players, not overleveraged homeowners, who received generous government bailouts in the aftermath of the crisis.

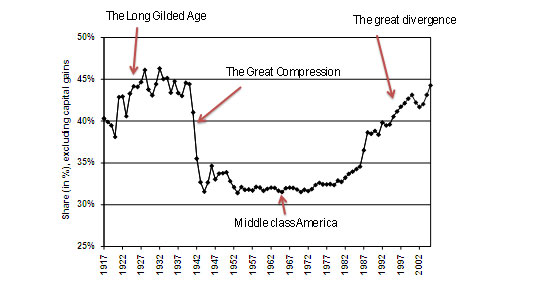

Acemoglu next asks whether there is evidence that the income distribution in the US worsened in the late 1990’s, leading politicians to respond by loosening the reins on lending to people who were “falling behind”? Income in the US has, in fact, become much more unequal over the past 40 years, but the timing doesn’t fit this story at all.

Fig. 1: Relative wage and education in the financial sector

This, of course, is also not new. Anyone who has read the Matt Taibbi article that famously referred to Goldman Sachs as “a great vampire squid wrapped around the face of humanity, relentlessly jamming its blood funnel into anything that smells like money,” has heard this explanation before. To paint the financial sector as a babe in the woods, coerced by the federal government to give loans to people who they knew in their heart of hearts would not be able to afford them once the rates reset in 18 months, is disingenuous at best, and more likely just plain bullshit. To distill the roots of the financial collapse to a policy of increasing home-ownership to the poor is ideological tunnel-vision and flat-out craziness.

Fig. 1: The Great Divergence

In closing, Johnson raises the excellent point that, in reality, the poor were essentially pawns (albeit, not totally without blame) in a much larger game:

The FCIC Republicans are right to place the government at the center of what went wrong. But this was not a case of over-regulating and over-reaching. On the contrary, 30 years of financial deregulation, made possible by capturing the hearts and minds of regulators, and of politicians on both sides of the aisle, gave a narrow private-sector elite – mostly on Wall Street – almost all the upside of the housing boom.

The downside was shoved onto the rest of society, particularly the relatively uneducated and underpaid, who now have lost their houses, their jobs, their hopes for their children, or all of the above. These people did not cause the crisis. But they are paying for it.

I agree. True, many took home loans they could not afford. But it takes two to tango, and there were other complicit parties as well. With the degree of income inequality in this country putting it on the same level as another place near and dear to my heart, the Philippines, the financial sector elite seem to have come out of this whole thing pretty damn well, while the poor are still poor, but are now jobless renters.

I would also recommend listening to an episode of the NPR podcast, Intelligence Squared US (“Oxford-style debating on America’s shores), titled “Is Washington to blame for the financial crisis?”