Microfinance is going through some major growing pains right now, hitting its first major challenge since it hit the mainstream in 2005 after Muhammad Yunus won the Nobel Peace Prize. The “silver bullet” of poverty alleviation that brought credit to those previously thought unworthy of a loan has seen an onslaught of criticism for failing to deliver on the lofty goals that its evangelists believed it could achieve (lesson: don’t overpromise).

Studies have shown that the impact of providing credit and Bridging Loans to poor women does not have a dramatic effect on poverty alleviation, and the success stories, at least in recent months, have been trumped by tales of aggressive loan-recovery tactics and suicides among poor borrowers in India. Portfolios of the Poor, a book written by four development economists with a healthy skepticism about the transformative effects of microfinance but optimism about its marginal impacts, showed that access to credit is actually less important than savings – access to a safe place to keep your money.

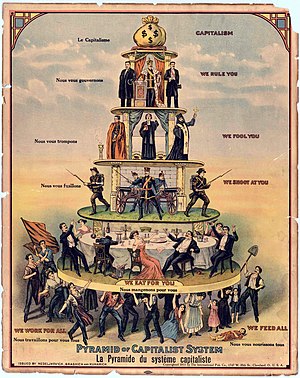

The big schism in microfinance since 2008 has been about where to get the money for operations. On one side, there is a group that believes microfinance must always focus on serving the needs of the poor and resist temptation to exploit borrowers with overly-exorbitant interest rates (I say “overly” because interest rates are, well, exorbitant). This camp, led by Muhammad Yunus, the spiritual and, until recently, actual leader of the Grameen Bank, condemns a profit motive. Instead, microfinance institutions (MFIs) should charge interest rates that will cover expenses and will finance expansion efforts. In other words, MFIs should be financially and operationally sustainable, but nothing more.

Proponents of the other side believe that, for microfinance to achieve its true potential and reach the billions of poor people without access to credit, it must tap into the vast financial coffers of the capital markets. To do so, microfinance needs to become attract investors with, at the least, a hybrid model focused on financial returns and social impact. There are still only a handful of MFIs of adequate scale to access the same type of capital that a normal company might access, at commercial rates.

Old habits die hard, and the motor patterns in my fingers that brought me to the Drudge Report so many times when I worked in a cubicle in Boston once again led me to page the other day. Living up to its reputation for sensationalism, it

Old habits die hard, and the motor patterns in my fingers that brought me to the Drudge Report so many times when I worked in a cubicle in Boston once again led me to page the other day. Living up to its reputation for sensationalism, it

A few years ago, I used to subscribe to Harper’s Magazine. The lead article in one of the issues was titled “Let them eat cash: Can Bill Gates turn hunger into profit?” It seemed interesting, but couldn’t really understand much of it at the time, since I didn’t know anything about food aid policy, or development in general. Just the other day I met someone who is working with the World Food Program’s Purchase for Progress program out here in Ghana. She asked me what I thought about the WFP and food aid in general. So I gave her my typical screed about food aid providing a market for surplus corn and soyabean production in the United States while calling it aid. And I talked about how flooding the market with low-cost (or no-cost) food may be necessary in the short-term, but is counterproductive in the long-run, since it undermines the competitiveness of the private sector in the areas where it is delivered and leaves the market in a state of atrophy. The conversation reminded me to go back and re-read the article. This time, I understand it much better.

A few years ago, I used to subscribe to Harper’s Magazine. The lead article in one of the issues was titled “Let them eat cash: Can Bill Gates turn hunger into profit?” It seemed interesting, but couldn’t really understand much of it at the time, since I didn’t know anything about food aid policy, or development in general. Just the other day I met someone who is working with the World Food Program’s Purchase for Progress program out here in Ghana. She asked me what I thought about the WFP and food aid in general. So I gave her my typical screed about food aid providing a market for surplus corn and soyabean production in the United States while calling it aid. And I talked about how flooding the market with low-cost (or no-cost) food may be necessary in the short-term, but is counterproductive in the long-run, since it undermines the competitiveness of the private sector in the areas where it is delivered and leaves the market in a state of atrophy. The conversation reminded me to go back and re-read the article. This time, I understand it much better. “The mining site, like others along the Irrawaddy River, is a concession given by Burma’s ruling military junta to local warlords or businessmen — who, it is believed, then make deals with Chinese financiers. China’s border is only 60 miles away.”

“The mining site, like others along the Irrawaddy River, is a concession given by Burma’s ruling military junta to local warlords or businessmen — who, it is believed, then make deals with Chinese financiers. China’s border is only 60 miles away.”

“There are two things that matter in politics. The first is money. I can’t remember the second.” – Mark Hanna

“There are two things that matter in politics. The first is money. I can’t remember the second.” – Mark Hanna

The other day I listened to

The other day I listened to

The answer to the title of this post is that China is using the same model of development to develop other countries that it used to develop itself. And China is a shining example of why its own model works. China has lifted hundreds of millions of its own people out of poverty and grown to be the second-largest economy in the world. Its growth in GDP is only matched by its increasing global influence around the world – an alternative superpower to deal with.

The answer to the title of this post is that China is using the same model of development to develop other countries that it used to develop itself. And China is a shining example of why its own model works. China has lifted hundreds of millions of its own people out of poverty and grown to be the second-largest economy in the world. Its growth in GDP is only matched by its increasing global influence around the world – an alternative superpower to deal with.

This isn’t

This isn’t

The other day a friend put me in touch with a friend of his who had just moved to Accra. She works the

The other day a friend put me in touch with a friend of his who had just moved to Accra. She works the