The crowded maternity ward of the government-run Dr. Jose Fabella Memorial Hospital in Manila, Philippines, on June 1, 2011. The ward, the busiest in the country, sees an average of 60 births every day. (Reuters/Cheryl Ravelo)

According to the United Nations’ Population Fund, the world population reached seven billion people today. The bulk of the growth is concentrated in a few countries – China, India, Brazil, etc. – yet one country, in particular, constitutes a disproportionate share, given its size. The Philippines – an archipelago nation of 7,100 islands with a combined land mass slightly larger than Arizona – has a population of 94 million, making it the 12th most populous nation in the world.

Unquestionable piety

The Philippines is one of the fastest-growing countries in the world in terms of population. The roots of its explosive growth date back to Spanish colonialism. Ferdinand Magellan laid the foundation of Spanish influence with his arrival in the Philippines in 1521, introducing what would ultimately become the most influential force in shaping the social policies of the country: Roman Catholicism. Today, 80% of the country is Roman Catholic. After Brazil and Mexico, the Philippines is the third-largest Catholic nation in the world.

Its representation among the people of the Philippines gives the Catholic Church a powerful influence over the direction of the country, with mixed results. In some cases, it has been a force for good. For example, the Archbishop of Manila helped precipitate the People Power Revolution – the largest non-violent revolution in world history – leading to the overthrow of the dictator Ferdinand Marcos. Unfortunately, its impact on family planning, reproductive health, and population growth in general, has been less productive.

The Roman Catholic Church is ardently anti-contraception, and its dogma has held back just about every piece of progressive family planning legislation introduced. In 1973, the Church released a position paper on the “population question” in the Philippines. Its stance is consistent with doctrine, condemning “artificial contraception” and promotion “natural family planning” as the only licit and moral form of contraception:

The Catholic Church teaches the necessity of responsible parenthood and correct family planning (one child at a time depending on one’s circumstances), while at the same time teaching that large families are a sign of God’s blessings. It teaches that modern natural family planning, a method of fertility awareness, is in accord with God’s design, as couples give themselves to each other as they are.

The sixth and final bullet holds the key to understanding the rapid population growth in the country:

In the Philippines, our underdevelopment, we believe, stems not so much from overpopulation as from injustice. While we are not absolutely opposed to the slowing down of our growth rate, we are against an antinatalist mentality, and we wish to emphasize the necessity for greater initiative and spirit of enterprise, a more just distribution of wealth and power, and a wiser use of our resources as solutions to our underdevelopment.

This philosophy – injustice trumps population growth in economic development – is as popular today as it was in 1973. It is an anti-Malthusian stance, saying that resource allocation, rather than availability, is the problem. And today, in debates over a controversial reproductive health bill, the Philippines continues to grapple with the question of how to deal with its growing population.

The Reproductive Health Bill would provide access to all effective forms of contraception and methods of family planning, including distribution of condoms and contraceptives to women unable to afford them. Schools would be required to teach health and sexual education and the government would integrate family planning and responsible parenthood to all anti-poverty programs. The Wall Street Journal gives some background on the bill and the opposition toward the new president, Noynoy Aquino, from the Catholic Church:

Since taking office at the end of June, Philippine President Benigno Aquino III, the son of pro-democracy icons Benigno Aquino Jr. and Corazon Aquino, has put his weight behind the idea that the government has a responsibility needs to inform people of family-planning choices.

Under the proposed legislation, government health authorities would be obliged have to provide information about family-planning methods, both artificial and natural. Government clinics would supply condoms and contraceptive pills and also give advice about other contraceptive methods. Abortion would remain illegal.

Church officials in September threatened Mr. Aquino, a practicing Catholic, with possible excommunication if he supports the family-planning and reproductive-health legislation. Conservative activists also reacted strongly. Eric Manalang, president of the Pro-Life Philippines lobby group, says legislation is unnecessary, noting that the country’s population growth has slowed from the 3.5% annual growth rate in the 1960s.

Proponents claim that, on a macro scale, rapid population growth and high fertility rates exacerbate poverty and hinder economic development by keeping poor families poor. Large families often lack resources to invest in education and healthcare for their children. Aside from the obvious health benefits in preventing the transmission of STDs and reducing unwanted pregnancies (44% of unwanted pregnancies in the lowest quartile are unexpected), 71% of the country supports the bill (though another study in 2009 showed that, when explained the components of the plan, 91% of Filipinos rejected the bill).

Proponents claim that, on a macro scale, rapid population growth and high fertility rates exacerbate poverty and hinder economic development by keeping poor families poor. Large families often lack resources to invest in education and healthcare for their children. Aside from the obvious health benefits in preventing the transmission of STDs and reducing unwanted pregnancies (44% of unwanted pregnancies in the lowest quartile are unexpected), 71% of the country supports the bill (though another study in 2009 showed that, when explained the components of the plan, 91% of Filipinos rejected the bill).

Opponents feel that the scientific evidence and economic rationale behind the theory, citing a study from 2003 by the Rand Corporation that claims “there is little cross-country evidence that population growth impedes or promotes economic growth.” They claim that condoms increase the incidence of HIV/AIDS and oral contraceptives are carcinogenic. The Wikipedia page has a good summary of the main arguments against a family planning bill.

None of these arguments seem very convincing to me. But that is besides the point. At its core, the debate is already settled in the minds of bill’s critics. That is because the Reproductive Health Bill is morally wrong in the eyes of the Catholic Church, and antithetical to devout Catholics in the country. But the moral basis for opposing the bill is rarely mentioned by critics. Instead, dubious science and cherry-picked quotes provide the “factual” basis for opposition. Just as gay marriage inevitably leads to the “destruction of the traditional family,” modern family planning and free contraceptives have deleterious social impacts. In both cases, an evidence-based opposition – built on flimsy assumptions and extrapolated conclusions – supports the moral conviction.

And the argument today is no different than it was in 1973. In the National Review a few months ago, Christopher White explained why he opposed the Reproductive Health Bill in the Philippines:

The current bill in the Philippines aims to provide a roadmap for “responsible parenthood.” The solutions presented to achieve this are a state recommended family size of two children per couple, mandatory government family-planning certification in order to receive a marriage license, and mandatory sexual education in all schools. This bill, in effect, focuses on what will go on in schools before the schools or the roads that lead to them are even built. Rather than looking internally to see what it can do to promote the family and improve their current working and living conditions, the Filipino government would seemingly rather penalize the family unit itself for the nation’s economic ills.

The argument is the same as that of the Catholic Church in the Philippines. Rather than focusing on limiting family size, the government should promote education and employment for its people. Sure, population growth could be a problem, but it pales in comparison to the social injustices affecting the underclass.

The argument is the same as that of the Catholic Church in the Philippines. Rather than focusing on limiting family size, the government should promote education and employment for its people. Sure, population growth could be a problem, but it pales in comparison to the social injustices affecting the underclass.

The government of the Philippines is certainly corrupt, and it could and should be doing more for the 30% of the population living below the poverty line. But denying the obvious link between poverty and family size (57% of families with seven children are in poverty, compared with 24% among those with two children) and crafting a flawed economic argument to support a moral position (without actually explicitly mentioning the religious rationale) is counterproductive.

White concludes with an anecdote from Singapore:

On February 3, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong of Singapore marked the beginning of the Chinese New Year by urging his citizens to have more children: “We also need Singaporeans to produce enough babies to replace ourselves, and that has proved extremely challenging.” In addition, the PM noted that additional children bring “more joy” to families. The Philippines would do well to heed Mr. Loong’s advice. Not only will they find more joy, but also, like their neighbors in Hong Kong and Singapore, they’re likely to find prosperity.

He doubles down, encouraging people in a country with one of the highest population growth rates in the world to have not less but more children. But Singapore and the Philippines are two very different countries – socially, economically, physically, demographically, and culturally. And, if Christopher White has been to either, which I doubt, he would surely understand this.

Family size correlates with poverty incidence in the Philippines. I don’t know whether having a large family makes it more likely for a family to live in poverty, or education and middle-class status make people less likely to have a large family. But either way, average family size shrinks as relative economic development increases.

What Christopher White and, to a much greater extent, the Catholic Church support has held back the Philippines for generations for decades. With some luck and a bit of political will from the new president, the Philippines will exchange the moral prescriptions of the church for a more practical approach. In doing so, the Philippines will quickly realize its potential.

Develop Economies Music Recommendation

My intention isn’t to say that everyone with a masters degree in international development and a resume overflowing with public sector and development experience is wrong about everything. Clearly, that experience is valuable in understanding context and knowing what has worked and not worked in the past. It is particularly relevant in the policy sphere – designing programs like

My intention isn’t to say that everyone with a masters degree in international development and a resume overflowing with public sector and development experience is wrong about everything. Clearly, that experience is valuable in understanding context and knowing what has worked and not worked in the past. It is particularly relevant in the policy sphere – designing programs like

Develop Economies often waxes philosophic from his armchair in Africa about China’s role in the development of the continent. For some, the China love-fest is rooted in the fact that bilateral trade is not patronizing, unlike aid. For others, China is a ruthless competitor – a less explicit colonialist than the Europeans. In this journal, Develop Economies tries to remain neutral, presenting the facts. But, in recent months, he has given a disproportionate amount of airtime to the views of the former group. So it is timely that Yuriko Koike, Japan’s former minister of defense and national security adviser, has a none-too-kind piece in Project Syndicate titled “

Develop Economies often waxes philosophic from his armchair in Africa about China’s role in the development of the continent. For some, the China love-fest is rooted in the fact that bilateral trade is not patronizing, unlike aid. For others, China is a ruthless competitor – a less explicit colonialist than the Europeans. In this journal, Develop Economies tries to remain neutral, presenting the facts. But, in recent months, he has given a disproportionate amount of airtime to the views of the former group. So it is timely that Yuriko Koike, Japan’s former minister of defense and national security adviser, has a none-too-kind piece in Project Syndicate titled “

The New York Times

The New York Times  1. Causality

1. Causality

I could go on, but it is not worth it. I have been reading politics for the better part of the last five years. I am not that old, and I understand that every generation thinks its political situation is worse than the ones that preceded it. But I swear – the discourse was never like this. Ronald Reagan, the hero of the National Review raised taxes 11 times during his presidency and supported amnesty for illegal immigrants who had laid roots in this country. It is absolutely amazing to me that people like this are even given the time of day when they posit arguments like this. The party of Ms. MacDonald has flown off the handle. But she is a symptom of a much larger, more nefarious problem with the political discourse in this country. The fact remains that the

I could go on, but it is not worth it. I have been reading politics for the better part of the last five years. I am not that old, and I understand that every generation thinks its political situation is worse than the ones that preceded it. But I swear – the discourse was never like this. Ronald Reagan, the hero of the National Review raised taxes 11 times during his presidency and supported amnesty for illegal immigrants who had laid roots in this country. It is absolutely amazing to me that people like this are even given the time of day when they posit arguments like this. The party of Ms. MacDonald has flown off the handle. But she is a symptom of a much larger, more nefarious problem with the political discourse in this country. The fact remains that the

Conversely, without those role models, you need to have a superhuman combination of motivation, maturity, and intelligence at a very young age to see the benefits of education and hard work. And even if you do, there is no guarantee that an education is going to make your situation that much better (and in today’s America, with income inequality at its highest levels in 70 years, that is increasingly true). One of the great paradoxes of education in countries with chronic high unemployment is that the economic returns to schooling are marginal when there are no jobs to absorb all the graduates. Does that make people who pull their kids from school “depraved”? Of course not. As Masket says, they are a victim of circumstances. In fact, from an economic and financial perspective, they are thinking rationally, which, as someone who believes that the God and the Free Market are the only paths to salvation, should appreciate. Of course French is one of a great many thinkers today who have cobbled together all of the

Conversely, without those role models, you need to have a superhuman combination of motivation, maturity, and intelligence at a very young age to see the benefits of education and hard work. And even if you do, there is no guarantee that an education is going to make your situation that much better (and in today’s America, with income inequality at its highest levels in 70 years, that is increasingly true). One of the great paradoxes of education in countries with chronic high unemployment is that the economic returns to schooling are marginal when there are no jobs to absorb all the graduates. Does that make people who pull their kids from school “depraved”? Of course not. As Masket says, they are a victim of circumstances. In fact, from an economic and financial perspective, they are thinking rationally, which, as someone who believes that the God and the Free Market are the only paths to salvation, should appreciate. Of course French is one of a great many thinkers today who have cobbled together all of the A friend posted an article on his Facebook wall titled “

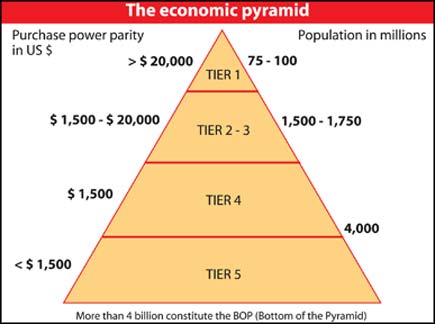

A friend posted an article on his Facebook wall titled “ There is a myth of a fortune at the bottom of the pyramid, according to Toyama. At least, that fortune is purely measured in market size and raw purchasing power. It should not be confused with an opportunity to offer products that alleviate poverty and make a bundle to boot. The rural and even urban poor are difficult markets to serve profitably. A disparate and sometimes non-existent supply chain makes getting products in the hands of consumers a challenge even for the biggest multinationals. Branding products for the poor, or subsidizing them, makes them less appealing to the middle class, who might pay more and create cross-subsidization opportunities (on this point, I think he is wrong, having seen the same solar lanterns we were selling to microfinance clients in the Philippines being sold in malls in Manila for twice the price). Not to mention, selling products to the poor is not going to help them out of poverty. Employment, in the form of manufacturing and labor-intensive work, is the key to growth. In short, it is possible to serve a social cause, and it is possible to make lots of money selling products to the poor. But to do both simultaneously? Very difficult.

There is a myth of a fortune at the bottom of the pyramid, according to Toyama. At least, that fortune is purely measured in market size and raw purchasing power. It should not be confused with an opportunity to offer products that alleviate poverty and make a bundle to boot. The rural and even urban poor are difficult markets to serve profitably. A disparate and sometimes non-existent supply chain makes getting products in the hands of consumers a challenge even for the biggest multinationals. Branding products for the poor, or subsidizing them, makes them less appealing to the middle class, who might pay more and create cross-subsidization opportunities (on this point, I think he is wrong, having seen the same solar lanterns we were selling to microfinance clients in the Philippines being sold in malls in Manila for twice the price). Not to mention, selling products to the poor is not going to help them out of poverty. Employment, in the form of manufacturing and labor-intensive work, is the key to growth. In short, it is possible to serve a social cause, and it is possible to make lots of money selling products to the poor. But to do both simultaneously? Very difficult.