cor·rup·tion (n.): Dishonest or fraudulent conduct by those in power, typically involving bribery

In Nairobi the other day, the police pulled over my taxi at a checkpoint. There were four people in the backseat, so the officer beckoned me, seated in the front seat, out of the car and said “You’re breaking the law – what do you want to do about it?” Fortunately, a friend sitting in the back felt strongly about not perpetuating the system of bribery and demanded to see their badge, since he was an employee of the embassy and wanted to report them. The police officer held up his gun and said “this is my badge,” while my friend explained to the “security officer” for the embassy on the phone that he was being harassed by police officers (I later went to dinner with another friend, who, it turns out, was the “security officer” on the other end of the line).

In Nairobi the other day, the police pulled over my taxi at a checkpoint. There were four people in the backseat, so the officer beckoned me, seated in the front seat, out of the car and said “You’re breaking the law – what do you want to do about it?” Fortunately, a friend sitting in the back felt strongly about not perpetuating the system of bribery and demanded to see their badge, since he was an employee of the embassy and wanted to report them. The police officer held up his gun and said “this is my badge,” while my friend explained to the “security officer” for the embassy on the phone that he was being harassed by police officers (I later went to dinner with another friend, who, it turns out, was the “security officer” on the other end of the line).

In Tamale in Northern Ghana, we took an illegal U-turn on our motorbikes and were stopped by a plain clothes police officer. He took away my friend’s keys and said we were going to the police station unless we gave him something to “make it better.” My friend, who works at the office of the regional coordinating council for the Northern Region, pulled out his phone and showed the officer the phone number of the regional minister, and explained that, because he did not understand what “make it better” mean, he was going to call the minister and ask for some clarity. We quickly got our keys back and were on our way.

In the Philippines, the 2010 election took place during my stay. Politicians send emissaries out to the different barangays (communities within a town) to distribute money directly to the people in exchange for votes. If a politician can’t buy a community, he rents a bus, loads it with booze and fried pork, and brings the members of the community to the beach for a party on Election Day.

The point I am trying to make is that, in many developing countries, corruption is a problem. It exists out in the open, in forms that are easy to see and easy to track. Some estimates place leakage in the Kenyan government due to corruption at 40% of GDP. As I discussed in a post the other day, the government is embroiled in a scandal over 4bn Kenyan shillings designated for free public education. Yes, corruption is a problem, and can be a major impediment to economic and social progress.

The western approach to Africa emphasizes good governance, democracy, and transparency in exchange for aid and development (tied or untied). Ghana is referred to as a “donor darling,” as its history of successful democratic elections has made the government a reliable (if not strategic) partner for donors in terms of economic development. In contrast, the Chinese approach in Africa has been to provide direct infrastructure investment in exchange for natural resource concessions, irrespective of governance. To the Chinese government, it is none of their business how another sovereign nation chooses to govern itself, particularly when it is in their interest to maintain the status quo.

Regardless of efforts to stem the tide of corruption, it exists and will likely continue to exist until certain fundamental underlying issues are addressed. I used to note that Filipinos are some of the most cynical people I’ve ever met about politics. Corruption is so pervasive in the system that (at least in local elections) people vote for the politician who is most adept at playing the game than the one who vows to change the rules. And when they talked about this, I used to say that corruption comes in many forms, and the United States is hardly immune. In fact, I would argue that corruption in the United States is arguably worse than in certain developing countries, if only because it operates under a veil of legitimacy.

K Street is a physical street in Washington D.C. It is also a euphemism for the lobbying industry, which, for the most part, calls K-street home. Wikipedia describes how lobbying works in the United States:

Lobbying (also Lobby) is the act of attempting to influence decisions made by officials in the government by individuals, other legislators or government actors, constituents, or advocacy groups. A lobbyist is a person who tries to influence legislation on behalf of a special interest or a member of a lobby. Governments often define and regulate organized group lobbying that has become influential.

Lobbyists use their time both with legislators, to explain the issues of the organizations which they represent, and with their clients to explain the obstacles elected officials face when dealing with these issues. Many of these lobbyists are employed by lobbying firms or by law firms, which retain clients outside lobbying, other lobbyists are employed directly by advocacy groups, trade associations, companies, and state and local governments. In 2007 there were over 17,000 federal lobbyists based in Washington, DC.[1]

Lobbying activities are also performed at the state level, and lobbyists try to influence legislation in the state legislatures in each of the 50 states. At the local municipal level, some lobbying activities occur with city council members and county commissioners, especially in the larger cities and more populous counties.

There are 17,000 people whose sole qualifications are their connections to lawmakers, and whose job it is to influence legislation in exchange for money. A rose by any other name would smell as sweet, and lobbying smells like corruption to me. In fact, I am not sure exactly how lobbying can be construed as anything but a legal form of corruption that operates with complete immunity from prosecution. Legally, politicians are not allowed to accept gifts from lobbyists. But, they can accept campaign donations to from political action committees (think Swift Boat Veterans for Truth) during a campaign year, increasing their likelihood that they’ll keep their job and their magnanimous donor will encounter what Michael Porter would describe as a “friendly regulatory environment.”

There are 17,000 people whose sole qualifications are their connections to lawmakers, and whose job it is to influence legislation in exchange for money. A rose by any other name would smell as sweet, and lobbying smells like corruption to me. In fact, I am not sure exactly how lobbying can be construed as anything but a legal form of corruption that operates with complete immunity from prosecution. Legally, politicians are not allowed to accept gifts from lobbyists. But, they can accept campaign donations to from political action committees (think Swift Boat Veterans for Truth) during a campaign year, increasing their likelihood that they’ll keep their job and their magnanimous donor will encounter what Michael Porter would describe as a “friendly regulatory environment.”

Yesterday, an article in Politico describes what Andrew Sullivan calls “Talk Radio’s Ideological Industrial Complex,” in which prominent talk radio hosts accept money from influential political think tanks in exchange for endorsements:

In search of donations and influence, the three prominent conservative groups are paying hefty sponsorship fees to the popular talk show hosts. Those fees buy them a variety of promotional tie-ins, as well as regular on-air plugs – praising or sometimes defending the groups, while urging listeners to donate – often woven seamlessly into programming in ways that do not seem like paid advertising.

“The point that people don’t realize,” said Michael Harrison, founder and publisher of the talk media trade publication TALKERS Magazine, “is that (big time political talk show hosts) are radio personalities – they are in the same business that people like Casey Kasem are in – and what they do is no different than people who broadcast from used car lots or restaurants or who endorse the local roofer or gardener.”

The Heritage Foundation pays about $2 million to sponsor Limbaugh’s show and about $1.3 million to do the same with Hannity’s – and considers it money well spent.

This is called the “politico-media complex,” and, to my mind, it is another form of corruption. The military-industrial complex – Harry Truman’s phrase for the unholy relationship between the defense industry and the government that Dylan sang about – is another form of corruption. So is the prison-industrial complex, which describes the connection between the drastic increase in the number of incarcerated Americans – by far the largest of any industrialized nation as a percentage of population – to the political influence of the private-sector prison lobby. Remember the Arizona immigration law? The one that legalizes racial profiling and is designed to stop “the Trojan horse destroying our country,” as described by Arizona state senator Russell Pearce? Well, that bill was influenced by, if not drafted by, the private-sector prison lobby, led by the Corrections Corporation of America. The business model of for-profit prisons is simple: revenue is directly correlated to the number of inmates being housed in the correctional facility. Illegal immigration – an issue that appeals to people’s basest tendencies, drawing on latent xenophobia and racism – is, frankly, a big market. This, from NPR:

This is called the “politico-media complex,” and, to my mind, it is another form of corruption. The military-industrial complex – Harry Truman’s phrase for the unholy relationship between the defense industry and the government that Dylan sang about – is another form of corruption. So is the prison-industrial complex, which describes the connection between the drastic increase in the number of incarcerated Americans – by far the largest of any industrialized nation as a percentage of population – to the political influence of the private-sector prison lobby. Remember the Arizona immigration law? The one that legalizes racial profiling and is designed to stop “the Trojan horse destroying our country,” as described by Arizona state senator Russell Pearce? Well, that bill was influenced by, if not drafted by, the private-sector prison lobby, led by the Corrections Corporation of America. The business model of for-profit prisons is simple: revenue is directly correlated to the number of inmates being housed in the correctional facility. Illegal immigration – an issue that appeals to people’s basest tendencies, drawing on latent xenophobia and racism – is, frankly, a big market. This, from NPR:

NPR spent the past several months analyzing hundreds of pages of campaign finance reports, lobbying documents and corporate records. What they show is a quiet, behind-the-scenes effort to help draft and pass Arizona Senate Bill 1070 by an industry that stands to benefit from it: the private prison industry.

The law could send hundreds of thousands of illegal immigrants to prison in a way never done before. And it could mean hundreds of millions of dollars in profits to private prison companies responsible for housing them.

Yes, that is corruption too. Food is another one. The agribusiness sector in the United States spent $1.3 billion on lobbying between 1998 and 2010, representing ~4% of the total, and the return on that investment has arguably had a greater impact on world hunger than do the corrupt politicians that preside over the hungry populations. The U.S. senate recently voted to repeal a $6 billion tax credit to ethanol producers, which probably existed in part due to the fact that presidential candidate Newt Gingrich received $300K in campaign contributions from biofuel lobbyists. Meanwhile, the world is in the midst of a serious food crisis. Fortunately, Mr. Gingrich and his constituents will not feel the sting, as they do not spend half of their income on food, unlike the 100 million people who were pushed into extreme poverty during the last food crisis back in 2008.

These are all forms of corruption. I am a realist, as readers of this blog know. Geopolitics is driven by oil and money, and that is not going to change. Bribery – financial or otherwise – greases the wheels of capitalism and is part of the game, for better or for worse. But I do think it is only fair to acknowledge the hypocrisy in demanding good governance from other countries. Because corruption comes in many forms, and with more complexes than I can count on two hands, the United States would do well to take a hard look at its reflection in the glass house before it decides to throw stones.

In Nairobi the other day, the police pulled over my taxi at a checkpoint. There were four people in the backseat, so the officer beckoned me, seated in the front seat, out of the car and said “You’re breaking the law – what do you want to do about it?” Fortunately, a friend sitting in the back felt strongly about not perpetuating the system of bribery and demanded to see their badge, since he was an employee of the embassy and wanted to report them. The police officer held up his gun and said “this is my badge,” while my friend explained to the “security officer” for the embassy on the phone that he was being harassed by police officers (I later went to dinner with another friend, who, it turns out, was the “security officer” on the other end of the line).

In Nairobi the other day, the police pulled over my taxi at a checkpoint. There were four people in the backseat, so the officer beckoned me, seated in the front seat, out of the car and said “You’re breaking the law – what do you want to do about it?” Fortunately, a friend sitting in the back felt strongly about not perpetuating the system of bribery and demanded to see their badge, since he was an employee of the embassy and wanted to report them. The police officer held up his gun and said “this is my badge,” while my friend explained to the “security officer” for the embassy on the phone that he was being harassed by police officers (I later went to dinner with another friend, who, it turns out, was the “security officer” on the other end of the line). There are 17,000 people whose sole qualifications are their connections to lawmakers, and whose job it is to influence legislation in exchange for money. A rose by any other name would smell as sweet, and lobbying smells like corruption to me. In fact, I am not sure exactly how lobbying can be construed as anything but a legal form of corruption that operates with complete immunity from prosecution. Legally, politicians are not allowed to accept gifts from lobbyists. But, they can accept campaign donations to from political action committees (think Swift Boat Veterans for Truth) during a campaign year, increasing their likelihood that they’ll keep their job and their magnanimous donor will encounter what

There are 17,000 people whose sole qualifications are their connections to lawmakers, and whose job it is to influence legislation in exchange for money. A rose by any other name would smell as sweet, and lobbying smells like corruption to me. In fact, I am not sure exactly how lobbying can be construed as anything but a legal form of corruption that operates with complete immunity from prosecution. Legally, politicians are not allowed to accept gifts from lobbyists. But, they can accept campaign donations to from political action committees (think Swift Boat Veterans for Truth) during a campaign year, increasing their likelihood that they’ll keep their job and their magnanimous donor will encounter what  This is called the “

This is called the “ The Philippines is ranked 139th out of 180 on the Corruption Perceptions Index, registering a 2.3 out of 10 (with 10 being the best). In 2007, it was the second-worst in East Asia, a few points behind the Indonesia. My friends in the Philippines used to joke that the only reason it didn’t have the lowest score is because it paid off the judges. But, in 2008, it

The Philippines is ranked 139th out of 180 on the Corruption Perceptions Index, registering a 2.3 out of 10 (with 10 being the best). In 2007, it was the second-worst in East Asia, a few points behind the Indonesia. My friends in the Philippines used to joke that the only reason it didn’t have the lowest score is because it paid off the judges. But, in 2008, it

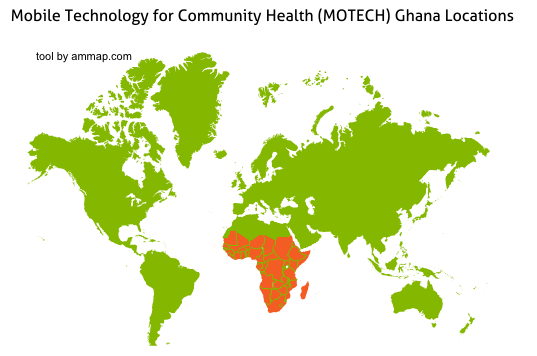

If you are a pregnant woman in the Upper East region of Ghana who has registered with MOTECH, you will receive this message during the fifth week of your pregnancy. Started in 2009, MOTECH is an mHealth platform created in partnership between the Ghana Health Service, Grameen Foundation, and Columbia Mailman Public Health School, with funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. It is designed to facilitate better medical information dissemination to rural areas and improve operational efficiency at community- and district-level health centers in one of the poorest regions of the country.

If you are a pregnant woman in the Upper East region of Ghana who has registered with MOTECH, you will receive this message during the fifth week of your pregnancy. Started in 2009, MOTECH is an mHealth platform created in partnership between the Ghana Health Service, Grameen Foundation, and Columbia Mailman Public Health School, with funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. It is designed to facilitate better medical information dissemination to rural areas and improve operational efficiency at community- and district-level health centers in one of the poorest regions of the country.

I’ve now been in Nairobi for two weeks and have settled in well. I moved into my fairly upscale apartment in Kilimani, a section of Nairobi that is the beating heart of the tech and social enterprise scene here. Up until last Saturday, I was sleeping on a mattress on the floor. The landlord wanted to deliver a new bed frame, so I needed to let the movers into the apartment. It was a total

I’ve now been in Nairobi for two weeks and have settled in well. I moved into my fairly upscale apartment in Kilimani, a section of Nairobi that is the beating heart of the tech and social enterprise scene here. Up until last Saturday, I was sleeping on a mattress on the floor. The landlord wanted to deliver a new bed frame, so I needed to let the movers into the apartment. It was a total

For my last three weeks in Ghana, I have been, in the words of my brother Kwesi, absolutely chilling out and taking in as much of what this great country has to offer before I leave. One of those incredible places was Cape Coast and Elmina, two towns a few kilometers apart in the Central Region of Ghana, where much of the citrus production takes place. Both are beautiful towns. On his first trip to Africa, Obama came here to speak. The economies revolve around fishing, and fishing towns, in my experience, tend to have a pleasant atmosphere. Cape Coast and Elmina are no exception, though they have a notorious and checkered past. They are home to the notorious slave castles that, for hundreds of years, functioned as the last stop for African slaves before boarding the slave ships for Europe and the Americas. The brutality with which the slaves were treated and the conditions in which they were kept is appalling. It is hard to believe that human beings could treat one another in such a despicable way. It is an important time in history to understand and to never forget.

For my last three weeks in Ghana, I have been, in the words of my brother Kwesi, absolutely chilling out and taking in as much of what this great country has to offer before I leave. One of those incredible places was Cape Coast and Elmina, two towns a few kilometers apart in the Central Region of Ghana, where much of the citrus production takes place. Both are beautiful towns. On his first trip to Africa, Obama came here to speak. The economies revolve around fishing, and fishing towns, in my experience, tend to have a pleasant atmosphere. Cape Coast and Elmina are no exception, though they have a notorious and checkered past. They are home to the notorious slave castles that, for hundreds of years, functioned as the last stop for African slaves before boarding the slave ships for Europe and the Americas. The brutality with which the slaves were treated and the conditions in which they were kept is appalling. It is hard to believe that human beings could treat one another in such a despicable way. It is an important time in history to understand and to never forget. Develop Economies is back after a brief hiatus. I have finished up my work on my current project and am now taking some time to appreciate some of the aspects of Ghana I hadn’t had a chance to enjoy previously. I spent a few days living with a rice farmer about 45 minutes by motorbike from Atsusuare in a small community along a lake fed by the Volta River. I did some work in the field (very minor – I can’t say I’m a great farmer), came across two cobra snakes, and biked an hour each way to the next village with electricity to charge my cell phone and camera. It was the first time I have ever actually experienced rural living, with no electricity, no running water, limited transportation (you have to call a motorbike to pick you from the neighboring town), and the persistent threat of snakebites, malaria, and other calamities that hang around waterlogged fields of paddy rice. I have discussed on this blog the different solutions to the problems of rural energy delivery and distributed power generation, to the problem of inefficiency of burning charcoal and the use of clean-burning cookstoves, and others. But I had never actually seen any of it or experienced it with my own eyes.

Develop Economies is back after a brief hiatus. I have finished up my work on my current project and am now taking some time to appreciate some of the aspects of Ghana I hadn’t had a chance to enjoy previously. I spent a few days living with a rice farmer about 45 minutes by motorbike from Atsusuare in a small community along a lake fed by the Volta River. I did some work in the field (very minor – I can’t say I’m a great farmer), came across two cobra snakes, and biked an hour each way to the next village with electricity to charge my cell phone and camera. It was the first time I have ever actually experienced rural living, with no electricity, no running water, limited transportation (you have to call a motorbike to pick you from the neighboring town), and the persistent threat of snakebites, malaria, and other calamities that hang around waterlogged fields of paddy rice. I have discussed on this blog the different solutions to the problems of rural energy delivery and distributed power generation, to the problem of inefficiency of burning charcoal and the use of clean-burning cookstoves, and others. But I had never actually seen any of it or experienced it with my own eyes.