Something strange is happening in the United States. Parallel sets of reality exist, disconnected from one another in the discourse over issues like taxes, the tea party, and the debt ceiling. In one reality, there is a very loud and public debate over the growing size of government and the intrusion on the lives of ordinary folks in the form of higher taxes and more restrictions. During the debate, the GOP opposition candidate made a bald, white Ohioan nicknamed “Joe the Plumber” the central point of his campaign. He was supposed to be representative of the millions of Americans who don’t want to see the socialist then-candidate Barack Obama to “spread the wealth around” and turn the country into a latter-day Soviet Russia. In fact, people were so convinced that Obama’s policies would destroy the American dream for hard-working middle America that they formed something called the Tea Party, an ideologically-pure subset of Republicans that are now almost certainly directly responsible for bringing the country to the brink of default on its debt, a first in American history.

The tea party and the middle class is incensed with the Democratic party for bringing the country closer and closer to communism. But, if you look at the chart above, which shows that the income gap is actually widening and has been for some time, exactly the opposite is true in the United States, as the country has become more capitalistic over time.

The tea party and the middle class is incensed with the Democratic party for bringing the country closer and closer to communism. But, if you look at the chart above, which shows that the income gap is actually widening and has been for some time, exactly the opposite is true in the United States, as the country has become more capitalistic over time.

This is other set of reality, which is supported by statistics: the United States is more unequal than ever. Wealth is more concentrated among the top 1% of earners than it has been since the the 1920’s, at the start of the Great Depression. The Bush-era tax cuts – a move to secure the political backing of the wealthy – disproportionately benefit the top earning segments of the country, yet they are vociferously defended by the Tea Party, a group that, as a generalization, stands to lose more than they will gain by their extension (which Obama did anyways at the end of 2010 in exchange for an extension of unemployment benefits – a move that certainly benefited many of those in the Tea Party that campaign against him). Capital gains are income earned from the sale of an investment – either in the stock market or from the sale of a company via a private equity firm, or some other vehicle. Because capital gains are taxed a lower rate than regular income taxes Warren Buffett, one of the world’s richest men, famously pays less in taxes every year than his secretary. Most recently and perhaps most disturbingly, according to the Pew Research center, the current wealth gap between whites, blacks and Hispanics – which now stands at an appalling 20 to 1, is the highest in history!

This is other set of reality, which is supported by statistics: the United States is more unequal than ever. Wealth is more concentrated among the top 1% of earners than it has been since the the 1920’s, at the start of the Great Depression. The Bush-era tax cuts – a move to secure the political backing of the wealthy – disproportionately benefit the top earning segments of the country, yet they are vociferously defended by the Tea Party, a group that, as a generalization, stands to lose more than they will gain by their extension (which Obama did anyways at the end of 2010 in exchange for an extension of unemployment benefits – a move that certainly benefited many of those in the Tea Party that campaign against him). Capital gains are income earned from the sale of an investment – either in the stock market or from the sale of a company via a private equity firm, or some other vehicle. Because capital gains are taxed a lower rate than regular income taxes Warren Buffett, one of the world’s richest men, famously pays less in taxes every year than his secretary. Most recently and perhaps most disturbingly, according to the Pew Research center, the current wealth gap between whites, blacks and Hispanics – which now stands at an appalling 20 to 1, is the highest in history!

But the chart below is the most damning of all. It shows the Gini coefficient – an indicator of income inequality and wealth distribution – by country. As of 2007, the United States, the global economic superpower and country in which nearly half of the population believes the current presidential administration is leading us down the path to socialism, had a Gini coefficient of 45, placing it just ahead of Uruguay, Uganda, and the Philippines, and just behind Cote D’Ivoire, Cameroon, and Iran.

By all accounts, the lower and middle class of America are doing worse than ever before, yet many in these segments have been the most vocal proponents of lower taxes and fiscal austerity during a time where government spending is probably pretty damn important to prevent the country from going into a double-dip recession. So why is this happening? The answer is quite literally complex. In any country – developed or developing – the top of the economic pyramid typically has the most to lose from higher taxes and the least to gain from social programs. Welfare, Medicaid, and other policies are critical to ensure social stability, preventing the disenfranchised from falling too far in desperation and reacting in the form of protest, but the immediate benefits of living in a country where social stability is the norm is not immediately apparent.

So, sometime in the early 2000’s, Karl Rove, Bush 43’s top adviser, solidified a Republican coalition comprised of three main groups: the fiscal conservatives (typically the top 10% of earners), the defense and foreign policy hawks, which were responsible for our multiple forays into nation-building in the Middle East, and the religious right, a large and disciplined voting block that are frequently single-issue voters concerned more with social issues than those of the public purse. The first group supplied the money for political campaigns (including, according to Jane Mayer and others, the “grass roots” Tea Party movement) and received favorable tax policies in return. The second group provided the ideological approach to governance, one of “American exceptionalism” in which it was the burden of the United States to restore order to a world plagued by non-democratic regimes that stood in the way of global dominance (i.e. access to oil). And, lastly, the the third group of evangelicals provided the vast network of foot soldiers motivated by their commitment to God to guarantee the right of life and defend the sanctity of marriage through federal and state legislation.

Signing the Bush tax cuts. Where are all the Tea Partiers?

Now, anyone who has spent 15 minutes reading an article on political philosophy while perched on the john knows that, from an ideological perspective, the amalgamation of positions that make up the platform of this three-pronged Republican party are full of contradictions. For one thing, the fiscal conservatives generally believe in limited government and minimal intrusion by the government on all matters, including the way we citizens choose to live our lives. If it were politically expedient and they did not need the numbers of the religious right, you can bet your bottom dollar that that sect of the Republican party would be pro-marriage, pro-choice, and pro-legalization, if only for economic reasons.

The hawks, which believe that spending as much as the next ten countries combined on defense is essential to the survival of our way or life (or so they say), consider any cuts at all to defense to be anathema. The “Bush Doctrine,” an ideologically-pure interventionist approach to foreign policy, which controversially supported the premise of preventive war (remember weapons of mass destruction in Iraq?), has cost the United States trillions of dollars fighting wars in God-forsaken parts of central Asia and the Middle East, where the people we are trying to help despise us and would like nothing more than to see us leave. The hawks are extraordinarily pro-Israel due to its strategic interest in controlling one of the most volatile regions in the world and guaranteeing that the price of oil – the underlying element of every foreign policy decision ever made – remains favorable to the United States. The following is a direct quote from Dick Cheney, the leader of the hawks within the Bush administration:

The hawks, which believe that spending as much as the next ten countries combined on defense is essential to the survival of our way or life (or so they say), consider any cuts at all to defense to be anathema. The “Bush Doctrine,” an ideologically-pure interventionist approach to foreign policy, which controversially supported the premise of preventive war (remember weapons of mass destruction in Iraq?), has cost the United States trillions of dollars fighting wars in God-forsaken parts of central Asia and the Middle East, where the people we are trying to help despise us and would like nothing more than to see us leave. The hawks are extraordinarily pro-Israel due to its strategic interest in controlling one of the most volatile regions in the world and guaranteeing that the price of oil – the underlying element of every foreign policy decision ever made – remains favorable to the United States. The following is a direct quote from Dick Cheney, the leader of the hawks within the Bush administration:

The good Lord didn’t see fit to put oil and gas only where there are democratically elected regimes friendly to the United States. Occasionally we have to operate in places where, all things considered, one would not normally choose to go. But, we go where the business is.

Now, if the platform of the Republican party truly reflective conservative political philosophy, the fiscal conservatives would be opposed to unnecessary wars for both economic and geopolitical reasons, while the religious right would be supporting pro-growth domestic economic policies – smart and efficient social programs, school choice, etc. But that isn’t the way it goes.

Remember that Reagan raised taxes 11 times during his two terms.

The religious right is the last angle of the tri-cornered hat of the Republican party. This group tends to be lower-middle class, pious, and socially conservative when it comes to just about everything. Abortion is murder and homosexuality is unnatural and a choice (“Thou shalt not lie with mankind, as with womankind: it is abomination.”). They believe in an original interpretation of the constitution, but they don’t really understand why. They pick and choose policies based on a believe that the separation of church and state is irrelevant if you can imbue the government with Christian values. Because of their socioeconomic status – blue collar, middle America – they tend to be relatively xenophobic and anti-immigration, despite the fact that smart immigration leads to the creation of more of the same types jobs that they are terrified of losing. They stand to lose much from the economic policies of the fiscal conservatives and the foreign policy prescriptions of the hawks, yet these issues are secondary to the social issues that the former two groups support more out of convenience than conviction.

This the construct of the Republican party circa 2007. Then the 2008 election occurred and the Republican nominee, John McCain, a man the religious right could hardly stomach due to to his relatively moderate positions on social issues, realized he would not be able to win the election with his first choice for vice-president, Joe Lieberman, a hawkish, fiscally-conservative democrat from Connecticut, and needed to make a radical attempt to shoot the moon and go for broke. So he chose Sarah Palin, because she was a good-looking, young woman – someone who added diversity to the ticket to complement a black nominee (Republicans are cynical to the end) – and she appealed to the evangelical base of the Republican party, which was McCain’s only ticket to the White House. She was perfect – someone who could be used to draw in the base, but without the intellectual or political clout to influence the policies of the White House once the party was in power. So, in a hastily-planned decision encouraged by Bill Kristol, editor of the Weekly Standard and intellectual figurehead of the Hawks, McCain unveiled Sarah Palin to the world.

Bill Kristol and Sarah Palin

But then something strange happened. Sarah Palin went rogue. She realized that she didn’t need the Republican establishment and jettisoned them in the middle of the campaign as she sought to chart her own political future. After McCain lost and America elected its first black president, the Koch brothers and other fiscal conservatives who felt threatened by a Democrat with a fairly liberal voting record were busy bankrolling a new grass-roots movement designed to oppose the socialist policies of the new president, Barack Obama. Sarah Palin, the new force in American politics, became its figurehead, and, once again, the movement soon realized that it no longer needed to heed the call of its masters (the Republican party establishment) and began to vote its own kind into the government in an effort to shut it down. The 2010 midterm elections saw sweeping victories for the Tea Party, with 80 or so freshman representatives heading to the House to tear the roof off the mothersucker. Those representatives are now at the center of the dangerous game being played with the debt ceiling, a political calamity that could have disastrous effects for years to come.

The impacts will not just be felt by the Tea Partiers themselves, who don’t really understand the complexity of the debt ceiling nor do they realize the implications for future job creation, growth, and employment. It is also going to be felt by the Hawks, who are now flailing wildly as they watch, for the first time since Reagan came to power in 1980, the defense budget becoming threatened. It will also be felt by the fiscal conservatives, who are going watch billions of dollars of their net worth disappear in an instant as the stock market plummets on the news that the United States, the last refuge of the conservative investor, has voted not to raise the debt ceiling, leading the ratings agencies to downgrade our debt and send us flying back into a recession. So, what has happened over the last decade, beginning with the fantasies of Karl Rove for a permanent Republican majority to the present debt ceiling calamity, is that an effort to control and harness the raw numbers of the stupid and convince them to vote against their interests, has backfired. The machine has become self-aware, and it no longer operates at the behest of its master.

I'm guessing he hasn't read Das Kapital

In Jewish folklore, there exists a creature called a Golem, which is a beast that can be activated and used to perform tasks by its master. It provides an instructive metaphor for this phenomenon:

The existence of a golem is sometimes a mixed blessing. Golems are not intelligent, and if commanded to perform a task, they will perform the instructions literally. In many depictions golems are inherently perfectly obedient. In its earliest known modern form, one story has Rabbi Eliyahu of Che?m creating a golem that became enormous and uncooperative. In one version of this story, the rabbi had to resort to trickery to deactivate it, whereupon it crumbled upon its creator and crushed him.

The other metaphor is a little bit more of a stretch, but I still think it works. It comes from the second Batman movie, “The Dark Knight.” In the scene, Alfred, the butler, is explaining to Bruce Wayne the mind of the joker, and why it is so difficult for him and others to understand:

Alfred Pennyworth: A long time ago, I was in Burma, my friends and I were working for the local government. They were trying to buy the loyalty of tribal leaders by bribing them with precious stones. But their caravans were being raided in a forest north of Rangoon by a bandit. So we went looking for the stones. But in six months, we never found anyone who traded with him. One day I saw a child playing with a ruby the size of a tangerine. The bandit had been throwing them away.

Bruce Wayne: Then why steal them?

Alfred Pennyworth: Because he thought it was good sport. Because some men aren’t looking for anything logical, like money. They can’t be bought, bullied, reasoned or negotiated with. Some men just want to watch the world burn.

The lead-in to this story begins with Alfred explaining how Batman pushed the criminals of Gotham City into a corner, leading them to turn to a man they didn’t fully understand – the Joker. The same principle holds true for the Republican establishment.

Why so serious?

The Republican party has created a Golem in the Tea Party, which has now become too strong and unwieldy for them to control. They are electing their own politicians – specifically, Michelle Bachmann, Rick Santorum, and Sarah Palin, to name a few – and developing their own platforms. Their xenophobia leads them to be increasingly isolationist when it comes to foreign policy, to the horror of the neoconservative hawks that ran amok during the Bush administration. They are nihilistic when it comes for fiscal policy, leaving themselves open to influence from politicians who want to exploit their misunderstanding of the debt ceiling to advance their own agendas, at the expense of the country. The permanent Republican coalition envisioned by Karl Rove has fragmented, as the beast of burden is no longer content to carry the weight and has learned to assert his political voice.

This all brings us back to why the United States is in its current predicament, and why the two realities highlighted at the beginning of this post exist. It is because the people who have controlled the country for the last 10 years (see the slope of the graph since 2000) used the voting power of the uneducated (politically and economically) masses to advance an agenda of low taxes on the rich that increases income inequality to unprecedented levels and simultaneously turned the budget surplus created by Bill Clinton into one of the largest deficits in history, in no small part due to the hawks, which led us into Iraq after Afghanistan and funded both wars with debt from China – something on the order of several trillion dollars.

Well, now the Golem has woken up after the beast that the hawks and fiscal conservatives didn’t fully understand has turned on them. And the result? Calamity for everyone.

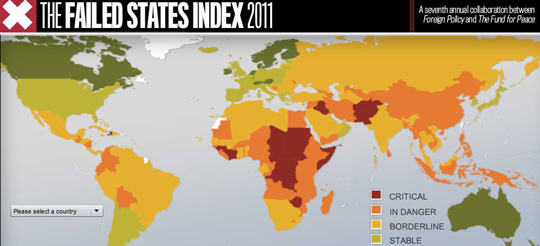

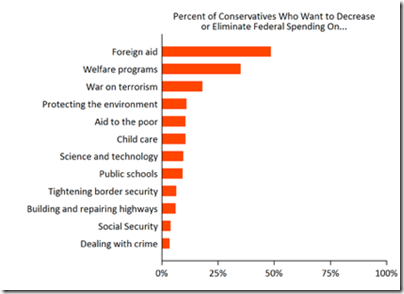

So why don’t Americans care about foreign aid? When asked to prioritize what they would cut from the budget, foreign aid is always number one. People assume that our foreign aid budget is ten times larger than its actually size (about 1%). I think there are a lot of reasons why Americans don’t care about famine, or, more broadly, foreign aid in general (clearly Americans care about famine, but I define “caring” as making a concerted sacrifice toward its elimination). Here are a few that come to mind:

So why don’t Americans care about foreign aid? When asked to prioritize what they would cut from the budget, foreign aid is always number one. People assume that our foreign aid budget is ten times larger than its actually size (about 1%). I think there are a lot of reasons why Americans don’t care about famine, or, more broadly, foreign aid in general (clearly Americans care about famine, but I define “caring” as making a concerted sacrifice toward its elimination). Here are a few that come to mind:

The tea party and the middle class is incensed with the Democratic party for bringing the country closer and closer to communism. But, if you look at the chart above, which shows that the income gap is actually widening and has been for some time, exactly the opposite is true in the United States, as the country has become more capitalistic over time.

The tea party and the middle class is incensed with the Democratic party for bringing the country closer and closer to communism. But, if you look at the chart above, which shows that the income gap is actually widening and has been for some time, exactly the opposite is true in the United States, as the country has become more capitalistic over time. This is other set of reality, which is supported by statistics: the United States is more unequal than ever. Wealth is more concentrated among the top 1% of earners than it has been since the the 1920’s, at the start of the Great Depression. The Bush-era tax cuts – a move to secure the political backing of the wealthy – disproportionately benefit the top earning segments of the country, yet they are vociferously defended by the Tea Party, a group that, as a generalization, stands to lose more than they will gain by their extension (which Obama did anyways at the end of 2010 in exchange for an extension of unemployment benefits – a move that certainly benefited many of those in the Tea Party that campaign against him). Capital gains are income earned from the sale of an investment – either in the stock market or from the sale of a company via a private equity firm, or some other vehicle. Because capital gains are taxed a lower rate than regular income taxes Warren Buffett, one of the world’s richest men, famously

This is other set of reality, which is supported by statistics: the United States is more unequal than ever. Wealth is more concentrated among the top 1% of earners than it has been since the the 1920’s, at the start of the Great Depression. The Bush-era tax cuts – a move to secure the political backing of the wealthy – disproportionately benefit the top earning segments of the country, yet they are vociferously defended by the Tea Party, a group that, as a generalization, stands to lose more than they will gain by their extension (which Obama did anyways at the end of 2010 in exchange for an extension of unemployment benefits – a move that certainly benefited many of those in the Tea Party that campaign against him). Capital gains are income earned from the sale of an investment – either in the stock market or from the sale of a company via a private equity firm, or some other vehicle. Because capital gains are taxed a lower rate than regular income taxes Warren Buffett, one of the world’s richest men, famously

Through its focused efforts to turn China into the world’s manufacturer, the Chinese government has pulled hundreds of millions of its people out of poverty. Companies like Tata Motors in India and BYD Auto in China are growing gangbusters on the backs of a burgeoning global middle class, a product of what Fareed Zakaria calls “

Through its focused efforts to turn China into the world’s manufacturer, the Chinese government has pulled hundreds of millions of its people out of poverty. Companies like Tata Motors in India and BYD Auto in China are growing gangbusters on the backs of a burgeoning global middle class, a product of what Fareed Zakaria calls “ There are two interesting points to be made here. The first is that the developing world is developing fast, and the bulk of demand in the coming decades is clearly going to come from emerging economies that are savvy enough to reap the benefits of globalization. The second point stems from a conversation I had with some friends last night at a swanky outdoor lounge bar in Nairobi surrounded by the TGIF Kenyan after-work crowd, all dressed to the nines and enjoying a mixed drink and calamari appetizer before dinner. It is this: the United States and Europe do not really appreciate just how fast the rest of the world is growing. The chart on the right shows year-over-year growth in retail sales. The developing world has averaged 10% a year, with hardly a blip from the financial crisis. It is starting from a smaller base, but such tremendous growth rates cannot be dismissed as poor countries simply transitioning to lower-middle income status. As a result of globalization, the tortoise isn’t just catching up – it is becoming the hare.

There are two interesting points to be made here. The first is that the developing world is developing fast, and the bulk of demand in the coming decades is clearly going to come from emerging economies that are savvy enough to reap the benefits of globalization. The second point stems from a conversation I had with some friends last night at a swanky outdoor lounge bar in Nairobi surrounded by the TGIF Kenyan after-work crowd, all dressed to the nines and enjoying a mixed drink and calamari appetizer before dinner. It is this: the United States and Europe do not really appreciate just how fast the rest of the world is growing. The chart on the right shows year-over-year growth in retail sales. The developing world has averaged 10% a year, with hardly a blip from the financial crisis. It is starting from a smaller base, but such tremendous growth rates cannot be dismissed as poor countries simply transitioning to lower-middle income status. As a result of globalization, the tortoise isn’t just catching up – it is becoming the hare.

It is this biologist’s opinion that Africa is moving from a period of equilibrium toward an evolutionary jump, with technology as the catalyst for systemic change. The paradigm has shifted, and the deep and broad telecom infrastructure has laid the groundwork for a revolution. Africa’s technological evolutionary paradigm will be different. It skipped the land line and went straight to the mobile phone. It skipped the desktop computer and adopted the laptop wholesale instead. The community bank became irrelevant with the creation of

It is this biologist’s opinion that Africa is moving from a period of equilibrium toward an evolutionary jump, with technology as the catalyst for systemic change. The paradigm has shifted, and the deep and broad telecom infrastructure has laid the groundwork for a revolution. Africa’s technological evolutionary paradigm will be different. It skipped the land line and went straight to the mobile phone. It skipped the desktop computer and adopted the laptop wholesale instead. The community bank became irrelevant with the creation of  watched the film “Blood Diamond” for the first time the other day. For those who have not seen it, the movie is graphic, placing the horror of armed conflict in Africa on full display. The director does not seem to pull any punches in terms of violence, choosing to show child soldiers doing drugs and killing women and other children. The main storyline, however, tracks the odyssey of Danny Archer, a white mercenary from Rhodesia played by Leonardo DiCaprio, as he and his guide, a Sierra Leonean fisherman named Solomon Vandy (Djimon Hounsou), whose son has been kidnapped by the RUF, and forced to take up arms, as they venture deep into the rebel-controlled bush to search for a diamond worth millions of dollars. The cynical opportunist Archer ultimately finds redemption with the help and support of an American journalist, Jennifer Connelly. In the end, Van de Kaap, a thinly-veiled reference to the DeBeers family I’m sure, is exposed for purchasing conflict diamonds, and the world opens its eyes to the terrible war in Sierra Leone.

watched the film “Blood Diamond” for the first time the other day. For those who have not seen it, the movie is graphic, placing the horror of armed conflict in Africa on full display. The director does not seem to pull any punches in terms of violence, choosing to show child soldiers doing drugs and killing women and other children. The main storyline, however, tracks the odyssey of Danny Archer, a white mercenary from Rhodesia played by Leonardo DiCaprio, as he and his guide, a Sierra Leonean fisherman named Solomon Vandy (Djimon Hounsou), whose son has been kidnapped by the RUF, and forced to take up arms, as they venture deep into the rebel-controlled bush to search for a diamond worth millions of dollars. The cynical opportunist Archer ultimately finds redemption with the help and support of an American journalist, Jennifer Connelly. In the end, Van de Kaap, a thinly-veiled reference to the DeBeers family I’m sure, is exposed for purchasing conflict diamonds, and the world opens its eyes to the terrible war in Sierra Leone.

The reality is that he is right – the majority of his readers probably would not read his articles if they were not written in the way he writes. The people who criticize him are, in general, people who already know, understand, and care about the issues he writes about. So it makes sense for them to assume he is being patronizing. But what they don’t understand is that they are not the readers he is targeting. Instead, his target is the woman from Florida who has never heard of the countries he writes about and, as a result of his stories, becomes incensed at the level of injustice that exists.

The reality is that he is right – the majority of his readers probably would not read his articles if they were not written in the way he writes. The people who criticize him are, in general, people who already know, understand, and care about the issues he writes about. So it makes sense for them to assume he is being patronizing. But what they don’t understand is that they are not the readers he is targeting. Instead, his target is the woman from Florida who has never heard of the countries he writes about and, as a result of his stories, becomes incensed at the level of injustice that exists.

Global warming was another issue. Over the last two decades, economists and climatologists have been contemplating the effects of global warming on food production. The consensus was that, while climate change and the corresponding shift in weather patterns would have an adverse impact on agriculture in certain regions of the world, a rising temperature could actually open up new pockets of arable land. The one bright spot of climate change was that the increased amount of carbon in the atmosphere would

Global warming was another issue. Over the last two decades, economists and climatologists have been contemplating the effects of global warming on food production. The consensus was that, while climate change and the corresponding shift in weather patterns would have an adverse impact on agriculture in certain regions of the world, a rising temperature could actually open up new pockets of arable land. The one bright spot of climate change was that the increased amount of carbon in the atmosphere would  This is a controversial position, but one with which I happen to agree. Large-scale commercial farming offers economies of scale that drive down the cost of production through mechanization, irrigation, and the consistent application of GAPs (good agricultural practices). In northern Ghana, it is difficult to offer mechanization services profitably to smallholder farmers because, frequently, the plots of land are not contiguous, meaning the tractor has to travel longer distances to serve the farmers, increasing fuel costs and adding to the per-acre cost. Not to mention, smallholder farmers often don’t have the resources to remove all the stumps and stones from their land, which, if run over by a tractor, will destroy it. The cost of importing replacement parts into the country is high, which is why if you go to northern Ghana, you will see tractors gathering rust on the side of the road.

This is a controversial position, but one with which I happen to agree. Large-scale commercial farming offers economies of scale that drive down the cost of production through mechanization, irrigation, and the consistent application of GAPs (good agricultural practices). In northern Ghana, it is difficult to offer mechanization services profitably to smallholder farmers because, frequently, the plots of land are not contiguous, meaning the tractor has to travel longer distances to serve the farmers, increasing fuel costs and adding to the per-acre cost. Not to mention, smallholder farmers often don’t have the resources to remove all the stumps and stones from their land, which, if run over by a tractor, will destroy it. The cost of importing replacement parts into the country is high, which is why if you go to northern Ghana, you will see tractors gathering rust on the side of the road.

In Nairobi the other day, the police pulled over my taxi at a checkpoint. There were four people in the backseat, so the officer beckoned me, seated in the front seat, out of the car and said “You’re breaking the law – what do you want to do about it?” Fortunately, a friend sitting in the back felt strongly about not perpetuating the system of bribery and demanded to see their badge, since he was an employee of the embassy and wanted to report them. The police officer held up his gun and said “this is my badge,” while my friend explained to the “security officer” for the embassy on the phone that he was being harassed by police officers (I later went to dinner with another friend, who, it turns out, was the “security officer” on the other end of the line).

In Nairobi the other day, the police pulled over my taxi at a checkpoint. There were four people in the backseat, so the officer beckoned me, seated in the front seat, out of the car and said “You’re breaking the law – what do you want to do about it?” Fortunately, a friend sitting in the back felt strongly about not perpetuating the system of bribery and demanded to see their badge, since he was an employee of the embassy and wanted to report them. The police officer held up his gun and said “this is my badge,” while my friend explained to the “security officer” for the embassy on the phone that he was being harassed by police officers (I later went to dinner with another friend, who, it turns out, was the “security officer” on the other end of the line). There are 17,000 people whose sole qualifications are their connections to lawmakers, and whose job it is to influence legislation in exchange for money. A rose by any other name would smell as sweet, and lobbying smells like corruption to me. In fact, I am not sure exactly how lobbying can be construed as anything but a legal form of corruption that operates with complete immunity from prosecution. Legally, politicians are not allowed to accept gifts from lobbyists. But, they can accept campaign donations to from political action committees (think Swift Boat Veterans for Truth) during a campaign year, increasing their likelihood that they’ll keep their job and their magnanimous donor will encounter what

There are 17,000 people whose sole qualifications are their connections to lawmakers, and whose job it is to influence legislation in exchange for money. A rose by any other name would smell as sweet, and lobbying smells like corruption to me. In fact, I am not sure exactly how lobbying can be construed as anything but a legal form of corruption that operates with complete immunity from prosecution. Legally, politicians are not allowed to accept gifts from lobbyists. But, they can accept campaign donations to from political action committees (think Swift Boat Veterans for Truth) during a campaign year, increasing their likelihood that they’ll keep their job and their magnanimous donor will encounter what  This is called the “

This is called the “